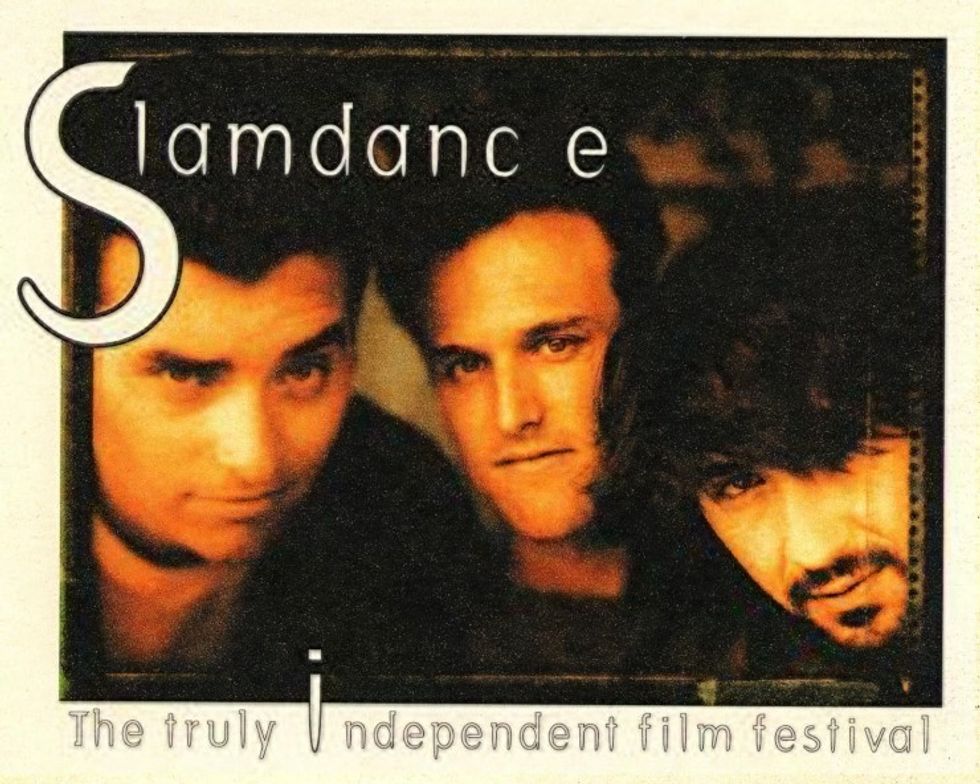

How to Start Your Own Film Festival: The Birth of Slamdance

This is an excerpt from Slamdance co-founder Dan Mirvish's book The Cheerful Subversive's Guide to Independent Filmmaking

From 1989-1994, independent film in the U.S. was 100% synonymous with the Sundance Film Festival. For filmmakers, the path to Sundance often led through the Independent Feature Film Market (IFFM) in New York (now called IFPWeek) – held at the time at the Angelika Theater on Houston. You’d finish your film, screen it at the IFFM, get discovered by Sundance programmers, get invited to the festival, and be the next Stephen Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, Richard Linklater or Kevin Smith!

The flip side was that if you didn’t get into Sundance you were dead in the water: You wouldn’t get distribution, you wouldn’t get an agent, and you even wouldn’t get into other regional or international festivals (they all just used the Sundance program as their quick guide for programming American indie films).

With that in mind, Dana Altman and I had our first real screening of Omaha (the movie) at the IFFM in 1994. Remember, this was the pre-internet age – no email, no web, no IndieWire or Facebook and cellphones the size of a sourdough baguette. After working largely in isolation from other indie filmmakers, we showed up in New York and met other filmmakers who’d also just finished their first films. Among others, we met Shane Kuhn and Brendan Cowles, who both lived in LA, but had also just shot a film in Nebraska, called Redneck.

One night during the IFFM, Dana had a sudden realization that we should get all these filmmakers together and create some sort of means of staying in touch and comparing notes. "There was a sense in the mid-90s that indie film - and Sundance in particular - was focused on New York or LA filmmakers,” says Dana. “Those of us with midwestern roots felt isolated and needed to crash the party to survive."

The next day, we had a big meeting with a number of other filmmakers in the lobby of the Angelika to discuss just such an idea, which people seemed to embrace in theory, if not in practice. We also all talked about Sundance, and said we’d see each other again there when we all got in! But we also shared tall tales of filmmakers who’d been rejected by Sundance, but did renegade screenings on their own in Park City.

There was a sense in the mid-90s that indie film - and Sundance in particular - was focused on New York or LA filmmakers

Twice in the early 90s, the New York collective Film Crash (founded by Matthew Harrison, Karl Nussbaum and Scott Saunders) held bootleg festivals in Park City hotel rooms. In 1994, a pre-South Park Trey Parker, Matt Stone, and Jason McHugh screened their film Cannibal the Musical, and separately, James Merendino screened his movie The Upstairs Neighbor in hotel screenings, too. In each case, the efforts had garnered at least a little press attention, so we all thought, those kind of screenings weren’t a bad “Plan B” in case our own films didn’t make it in.

Meanwhile, we were all begging the Sundance programmers to come to our respective IFFM screenings. With Omaha (the movie), since we were the rare film with a color poster. (Thanks to a local Omaha ad agency, which inexplicably gave us a horizontal poster. When we put it in vertical poster cases, invariably people would twist their necks trying to read the title of our film.) And since we got Robert Altman to come to our screening, we wound up being one of the buzzed-about films of the IFFM, according to The Hollywood Reporter. One junior Sundance programmer was at the screening and said he liked the film.

We had a major indie distribution exec tell us she loved the film and wanted to pick it up...if we got into Sundance. I got a fancy Hollywood agent out of the IFFM. Many years later, I heard that both Miramax and Fine Line were stalking us at the Angelika, and if one company had made an offer on the film, the other was poised to counter it. Sadly, neither made an offer. December rolled around, and Sundance made its selection announcement.

Of the 95 completed narrative feature films at the IFFM, Sundance did not select a single one. We were crestfallen.

The next morning, Shane Kuhn called me up: He said why don’t we take Dana’s amorphous idea about filmmakers working together and combine it with the Plan B of renegade screenings at Sundance. We’ll all share resources and put on our own alternative film festival during Sundance! I figured – sure thing!

We had nothing to lose, and everything to gain.

I drafted a list of potential names for the festival (including “LoserFest95”), but when Brendan came up with “Slamdance: Anarchy in Utah,” we all knew that was a keeper (and would lend itself well to a t-shirt and poster). Shane had spent a year at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, and was able to get its film department to agree to host Slamdance in its screening rooms on campus (we assumed that it was close enough to Park City that we’d get Sundance audiences coming to check us out).

We started contacting other filmmakers, mostly the ones we’d met at the IFFM. One director who lived in LA, Jon Fitzgerald, seemed organized, so we got him involved early. A filmmaker named Paul Rachman, who’d just made the short Drive Baby Drive, heard what we were up to, and he suggested we do a whole section of shorts, in addition to features. When he said that his producing partner was a trained projectionist, we decided we should let them in.

I knew a guy at Variety who ran a front-page story about Slamdance on the slow news week before Christmas, announcing what we were up to. He didn’t indicate a way for other filmmakers to get in touch with us but did mention that I had a seasonal job at The Good Guys electronics store in Westwood.

So filmmakers started showing up in the store, and Shane and Jon would sometimes come by at the end of my shift and we’d watch submissions on the big screen. Once, I was in the middle of selling a 13-inch, Sony TV to Kevin Pollak (who was getting ready to go to Sundance with The Usual Suspects). Joel Michaely, who’d helped produce a film directed by TV’s Punky Brewster, Soleil Moon Frye, ran up to me and submitted his VHS tape for Slamdance. Pollak was stunned, but I still managed to talk him into the 5-year extended warranty!

The Variety article was picked up by the nascent America Online network, as part of its entertainment newsfeed (AOL had a deal with Variety at the time). Philadelphia filmmaker Eugene Martin, in particular, heard about Slamdance through AOL and he contacted us. Altogether, we wound up with a dozen features and a dozen shorts eager to combine resources and put on a show.

That couple of months between announcing Slamdance and actually putting it on was a little nerve-racking. The festival director at Sundance left an intimidating voice message on Shane’s answering machine. Filmmakers who were friends of ours and had committed to Slamdance were getting cold feet and dropping out. Dana called Robert Altman, and told him we had this crazy festival idea, and asked if we should be worried that we would wind up being blacklisted by Sundance. Bob thought about it a moment, and said decisively, “Eh, fuck ‘em.” The Pope of Indie Film had blessed Slamdance – what more could we want? (Of course, 25 years later Altman is dead, and we’re still blacklisted....so I’m not sure how that worked out.)

Dana called Robert Altman, and told him we had this crazy festival idea, and asked if we should be worried that we would wind up being blacklisted by Sundance. Bob thought about it a moment, and said decisively, “Eh, fuck ‘em.”

The University of Utah’s film department got nervous that they’d lose all their perks with Sundance and at one point they told us they were dropping out of the arrangement. Oddly, it was the head honcho at Sundance that eventually told the University to stick with us, because he knew that Sundance would get decimated in the press if it came out that they had quashed us. Honestly, at that point I was hoping we’d get shut out. We would indeed have gotten amazing press and wouldn’t have had to do all the hard work of running a festival. Sadly, we had to drive to Utah and figure out how to run a film festival!

Almost all the filmmakers stayed in one condo in Salt Lake City not far from the University. We realized almost as soon as we started our screenings that no one from Park City was coming down the mountain to find us in Salt Lake City. (But on the map, they looked sooo close together!) Filmmakers Lise Raven and Frank Hudec (who had a film called Low) led the charge and rented a 16mm projector from a vendor in SLC. I drove with them in the back of their rental compact car – a rolled up screen sticking out my window, blizzard snow blowing in my face.

We went to one of the main hotels in Park City, the Prospector Inn, and found a friendly night manager who had no qualms about renting us a tiny conference room. It was 30 feet down the hall from the hotel’s big conference room, which was one of Sundance’s main screening venues. We used the lobby pay phone to call our compadres in Salt Lake and told them to haul ass up the mountain. Meanwhile, we asked the pimply-faced young night manager if we could borrow his Xerox machine. We ran off a couple hundred fliers indicating that Slamdance had made it up the hill to Park City! By the morning, the Sundance wait line went right past our little screening room, and we scheduled our films for 15 minutes after each Sundance start time. Their overflow crowd walked right into our free screenings!

We started running all our 16mm films at the Prospector, in addition to keeping all our screenings going at the University, including all our 35mm prints. By the middle of the week, a filmmaker named Chris Glatis called the condo and asked if he could get his short film into Slamdance. We politely told him that we were half-way done with the festival, so it was too late. That’s too bad, he told us. He had rented a 35mm projector and was running his film at the Yarrow Hotel in the heart of Park City already. Really, you have a working 35mm projector in the middle of Sundance? Congratulations, Chris! You’re in Slamdance!! So we co-opted his projectors and were able to start running our 35mm films (including Omaha (the movie)) in one of the main hotels at Sundance.

By then, a few real Sundance filmmakers were dropping by to see our shenanigans. Oscar- nominated animator Bill Plympton, who had a film in Sundance that year, came to watch Omaha (the movie) and Drive Baby Drive. Sundance jurors Whit Stillman and Samuel L. Jackson heard what we were up to (Sam’s wife LaTanya Richardson was in a Slamdance film). One unnamed Sundance competition feature filmmaker (who chooses to remain anonymous, even now!) told me the Sundance festival director warned him to stay away from those Slamdance guys: “They’re troublemakers!”

1995 was a pivotal year in indie film. It was at around this time that Miramax became part of Disney, New Line became part of Fine Line, and Sundance was the epicenter for this Hollywood-ization of indie film. It was at the festival that year that Fox launched Fox Searchlight (with Brothers McMullen) and within a couple years, every studio had its own independent film division. Sundance had embraced the limelight, showing more films by second-time directors, films with bigger stars and budgets, and films with distribution deals already in the works. It had largely forgotten about the first-time directors like us Slamdancers who had been so inspired by that first generation of Sundancers.

One unnamed Sundance competition feature filmmaker (who chooses to remain anonymous, even now!) told me the Sundance festival director warned him to stay away from those Slamdance guys: “They’re troublemakers!”

Consequently, the press was turning on Sundance. Slamdance was the perfect sidebar story to write: A group of renegade directors holding onto the true indie spirit! After interviewing me about Slamdance, The New York Times declared us to be a group of “cheerful subversives” (and clearly, that description has stuck).

We found ourselves, Slamdance and our films mentioned in newspapers and magazines around the globe.

We’d finally broken through the Sundance hex: Our films got invited to other regional and international festivals (often playing side-by-side with Sundance films), some films got distribution and filmmakers got agents. By the end of the week, there was a feeling that Slamdance was working so well we should try it again the next year. Filmmaker Peter Baxter (who’d aptly enough produced the Slamdance feature Loser) and I met with the Yarrow Hotel manager, and we put down Peter’s credit card as a deposit for the next year.

It may have been groundbreaking in the U.S., but in the international context of film festivals, what we started with Slamdance was not so unique: In 1969, the French Directors Guild, including such luminaries as Luis Malle and Robert Bresson, started its own sidebar fest at Cannes called Directors Fortnight (aka Quinzaine des Réalisateurs). Disgruntled critics (aren’t they all?) started their own section at Cannes called Critics’ Week (Semaine de la Critique) in 1962. Both sections are still going strong 50-plus years later, and are still run completely independently from the official sections in Cannes.

Of course, this tradition dates even farther back to the Salon de Refusés (“exhibition of rejects”) in France starting in 1863, where painters like Courbet and Manet staged their own unofficial art show in defiance of Emporer Napolean III. Now, Robert Redford may be short, but he’s no Napolean. In 1996, he was asked about Slamdance and called us “parasites” in Interview Magazine. He was right, of course, but it was still the best press we could have gotten, ensuring our street cred for years to come.

Like in an old western, Sundance had pull with the Sheriff and city council and tried to kick us out by whatever legal means they could try.

Slamdance also wasn’t totally unique in the U.S. Plus or minus a year from when Slamdance started also saw the launches of other significant festivals like South-by-Southwest’s film fest, the New York and Chicago Underground Film Festivals, the Hamptons Film Festival, the Los Angeles Independent Film Festival (later called the Los Angeles Film Festival). With the addition of AFI’s Film Fest in LA, and Tribeca in New York (started in the wake of 9/11), and the rise in prominence of Toronto’s festival, Sundance’s absolute hegemony over North American indie film premieres would be over (sort of).

Sundance tried to squeeze us out of Park City for years. The festival would outbid us for every venue we could find. After the Yarrow caved to Sundance in our third year, we found a friendly family-run hotel at the top of Main Street called the Treasure Mountain Inn (TMI).

Unlike most of the corporate-owned hotels and resorts in town, the TMI was run by Thea Leonard and Andy Beerman, a mountain-town hippie couple who’d been spurned by Sundance in prior years. Like in an old western, Sundance had pull with the Sheriff and city council and tried to kick us out by whatever legal means they could try. But 25 years later, the Sheriff has long since retired and the TMI’s Andy is the mayor. The locals love us, by and large, because they have an easier time getting tickets to Slamdance events than Sundance ones.

Peter Baxter is still running the festival, and we’ve largely stuck to our original mission. The main competition is devoted to first-time directors, with small budgets and no distribution in place. We’re still at the Treasure Mountain Inn, which I’ve affectionately dubbed a “snowball’s throw across the street from Sundance.” We have two small (hot and cramped!) screening rooms and a crowded lobby at our disposal every year which gives Slamdance a warm intimacy that’s somehow absent from Sundance.

Slamdance has minted Oscar winners, Palme d’Or winners and countless filmmakers who’ve gone on to show their second or third films at Sundance

And of course, we have an annual Hot Tub Summit at the TMI’s massive jacuzzi. Audiences come for both festivals, and the folks who now run Sundance have finally warmed to our existence...a little!

The films in Park City may not spin the world’s turnstiles, but the filmmakers who make them most definitely will. Slamdance has minted Oscar winners, Palme d’Or winners and countless filmmakers who’ve gone on to show their second or third films at Sundance. But if the proof is in the pudding, then take a slurp of this:

Just looking at first-time directors who’ve screened over the first 21 years at Slamdance, their worldwide box office gross for films they’ve directed or produced is more than $16 billion (according to Box Office Mojo). It’s also worth noting that the filmmakers currently behind the reigns of the Marvel, DC and Star Wars universes are Slamdance alumni. Hollywood? You’re welcome.

Sure, there will be the naysayers who wonder if most of that money is just from Christopher Nolan and his producer/wife Emma Thomas. Indeed, $5 billion or so is. (Not too shabby for a couple who could barely get 14 people to their first Slamdance screening of Following. Needless to say, their marketing efforts have improved.)

The list of financially successful Slamdance alumni includes such successful filmmakers as Rian Johnson (The Last Jedi), Oren Peli (Paranormal Activity), Marc Forster (World War Z), Jon M. Chu (Crazy Rich Asians), Seth Gordon (Identity Thief), Gina Prince-Bythewood (Beyond the Lights), Mike Mitchell (Shrek Forever After), Lynn Shelton (Laggies) and Joe and Anthony Russo (Captain America 2 and 3, Avengers Infinity Wars).

It’s also worth noting that the filmmakers currently behind the reigns of the Marvel, DC and Star Wars universes are Slamdance alumni. Hollywood? You’re welcome.

The Slamdance list of alumni directors includes many international filmmakers who’ve enjoyed great success worldwide, including South Korean auteur Bong Joon-Ho (Snowpiercer, Okja, The Host) and Frenchman Frédéric Forestier (Astérix Aux Jeux Olympiques). In both cases, their first times on American soil were to present their earliest films at Slamdance.

Oh, and that’s just the first-time directors Slamdance showcased in competition. If you add in directors we’ve screened out of competition (typically not their first film), the worldwide collective gross adds up to over $18 Billion. That’s more than the annual GDP of Albania. And if you start to include actors, producers and others that have been a part of Slamdance (ie. Ben Affleck, Mark Ruffalo, Vince Vaughn, Roger Corman, et al), there’s no telling how high you could tally.

Most film festivals that have been around for 20 years or more can probably boast similar numbers, and I’m sure Sundance itself is no exception. But what’s unique about Slamdance is it’s actually programmed and organized by its own alumni filmmakers, and we’ve created a unique community unrivaled by any organization our size.

When Hollywood inevitably does ignore us, who do we have to turn to? The most important connections Slamdancers make aren't the agents, producers, distributors or press.

Nope.

It's each other.

what’s unique about Slamdance is it’s actually programmed and organized by its own alumni filmmakers

Slamdancers are friends, colleagues, codependents for life. Slamdance is group therapy without the therapy, and frequently not in groups. "By filmmakers for filmmakers" is more than just an empty festival slogan in search of punctuation. When we need to borrow a camera, bootleg editing software or just get a referral on a good criminal defense attorney, Slamdancers call on one another. When we've been dropped by our agents, screwed by our distributors, and ignored by festivals the world over, we know that there will always be a plate of garlic chicken and a room full of fellow Slamdancers with whom to share our pain and flaunt our joy. That's why we're different, and that's why we're still around.

On the occasion of the 25th edition of the Slamdance Film Festival, this is an excerpt from festival co-founder Dan Mirvish's Focal Press book, The Cheerful Subversive's Guide to Independent Filmmaking. Dan will be signing copies in Park City at Dolly's Bookstore on Monday, January 28, from 2-4pm. Dan's newest film, Bernard and Huey, is available on Amazon Prime.