'Westworld' Editor Shares His Process and What You Can't Learn in Film School

If you ever want to work on a big Union Television show, it helps to know how that kind of show works. Assistant Editors know how it all goes down.

Four days into his gig as assistant editor on Season 2 of HBO's Westworld, Yoni Reiss found himself sorting through the results of one shooting day: seven cameras and 10-12 hours of footage.

Luckily, Reiss was in his element. If the thought of being handed that is making your palms sweat, then you're not alone. An amazing show like Westworld would be a dream for many post-production artists to work on, but what it takes to get there is much more murky for most of us. Yoni Reiss was kind enough to sit down with No Film School to demystify what it’s like to be an assistant editor on a show of this scale, and in the process explain to us how every element of post-production comes together.

Reiss had always been interested in editing. Fresh out of high school he realized he loved the way you could wrestle with footage for hours in front of the computer. That led him ultimately to a Masters in film editing from AFI, after which he he bounced around Los Angeles on every kind of editing job he could get to make a living. One day, he got a call from an old AFI friend, a woman named Anna Hauger. Hauger was an assistant of Season 1 of Westworld, and had gotten promoted to editor. She needed an assistant of her own that she could rely on. After a series of interviews with Westworld producers, Reiss got the job. (Cue the robot horse whinny!)

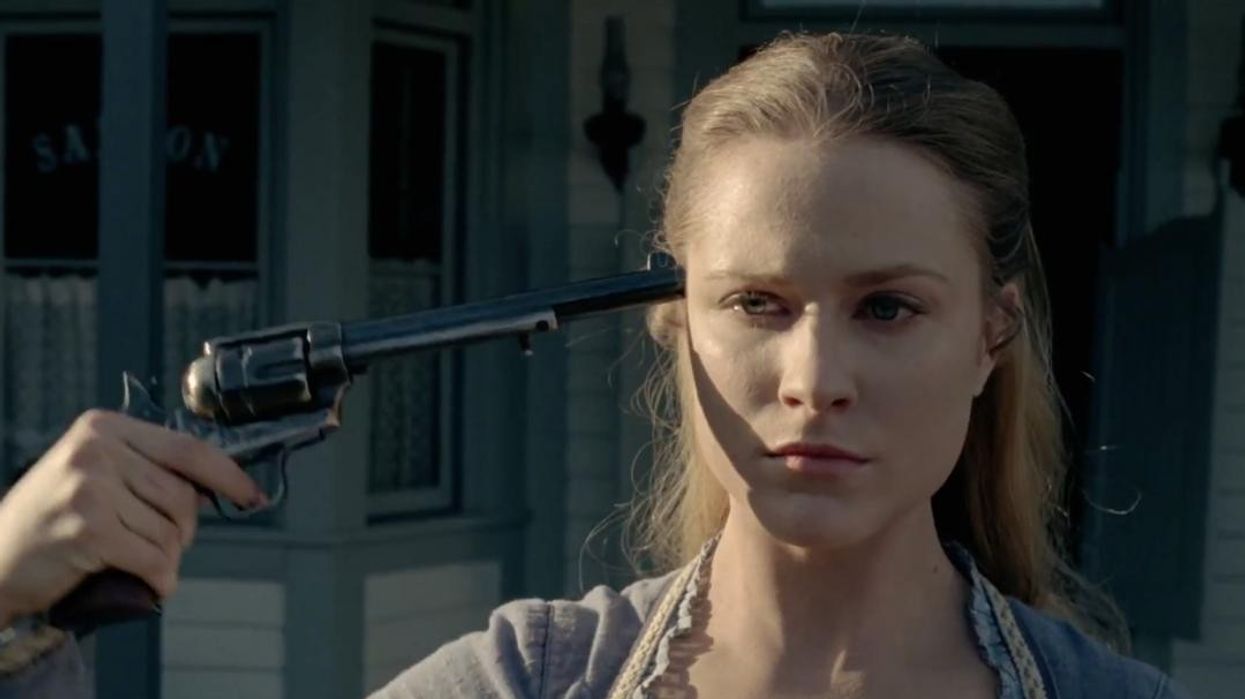

Reiss explained to No Film School what he was in charge of on the exciting madness of an HBO series that follows over 20 characters in 10 episodes, is set in an android-hosted Wild West theme park of the future, and shoots on film. Film! We’ve broken down our conversation with him into five important categories that clear up not only what happens in post-production to bring a show to life, but how to be the best assistant editor you possibly can.

What to expect when you go from cutting indies to working Union TV

Prior to getting in the union and landing Assistant Editor on HBO’s Westworld and now Watchmen, Reiss had to work his way from the bottom like everybody.

He started with a 7:00 pm to 4:00 am gig on a show called Stupid Suspects which featured moments like people walking into a 7 Eleven, drunk and naked, trying to buy cigarettes. With his Master’s of Fine Arts, Reiss could be found blurring out genitals in his edit bay.

Happy Friday night!

But Reiss also cut indie films, from Guadalupe the Virgin to In Organic We Trust. He got his first big break on the show Brockmire, and from there continued to move into bigger, more complex productions. Below he explains that while an indie film is about rolling up your sleeves with what you've got (and he still edits them transitioning to a union gig requires the opposite mentality.

NFS: What's sort of the biggest difference between cutting an Indie film and working on something like Westworld, an HBO show?

Reiss: I'd say definitely the scale of the productions. On an Indie film you might get an hour and a half of footage a day with one camera. On Westworld, you could get up to 10-12 hours of footage a day. You have 3-7 cameras. Sometimes they're shooting 2 or 3 units a day. In terms of the scope of everything, there's a lot more footage coming in.

I think there's also a much bigger support staff. For an indie film, when you're cutting, you probably do a lot of your own visual effects and things like that. [On]Westworld, we had a whole visual effects team. On an Indie film, you don’t have that. That can mean less bureaucracy sometimes. It's usually you, the director, the producer. On a larger scale, you do your directors cut, then you do your producers cut, the showrunner will come in, the studio has notes. When you're definitively editing more in a union world, there are many more layers of feedback, and also the deadlines are often tighter. There's a lot of Indie films submit unfinished work to Sundance or to Cannes, yet there's no unfinished work that goes on TV. If they have an air date, it's all got to be done by then.

How to make sure you don’t screw up on your very first day as an assistant editor

You get an assistant editor gig, now what?

For Reiss, to hit the ground running without any catastrophic mistakes means working seamlessly with a sizeable post crew of 20-25 people, helmed by a post-producer Stephen Semel. And that starts with making sure all the footage is there.

NFS: Everything about Post-production on Westworld would be complicated. Can you walk us through your team and how you get started with the workflow?

Reiss: I'd get in there at 9:00 in the morning. I would get everything into the system. So when I get dailies, my first thing is, make sure first and foremost, that we have everything.

Westworld shoots on film, which is not typical these days. When you shoot digitally, you get all the shots. A file doesn't get corrupt. When you shoot on film, it could be setup with four cameras and on the third take, all of the sudden, you have two cameras. You've got to really sort of go to the cameras reports, figure it out.

Oh, one camera rolled out, the other was a magazine jam or something. There are more variables in film and a lot more detective work. So priority number one was always making sure we have everything. Do we have to go back to the dailies house to look at something? Was something mislabeled?

You could be shooting hours and hours of dailies through multiple units, it was detective work to get everything in the system. Because you'd hate to be there six weeks later when the director is like, "Oh, where is that one great shot I got," and I hadn't seen it, my editor hadn't seen it. That's never a situation you want to be in. So that is priority number one: get everything in the system. Get eyes on it.

Because you'd hate to be there six weeks later when the director is like, "Oh, where is that one great shot I got," and I hadn't seen it, my editor hadn't seen it. That's never a situation you want to be in.

On Westworld, we'd shoot for 12-15 days, and then there’d be four days afterward where we get an editor's cut to put everything together, and that's when we'd get as many temp visual effects as we could in, as many temp music edits, and we'd do a lot of temp sound design. It’s all going be changed anyway, but because you're going to live with these episodes for 4-6 months, you try to get as good a production value as you can knowing that eventually professionals will come and do their sweetening with it.

After the director's cut, we got four days. That's when the various producers’ cuts would come in. HBO, because it's not week-to-week network, they would shoot everything out, and then after all of production, after they finished all ten episodes, then they'd start locking them. Which, if you were working on NCIS or something, you'd constantly be locking as you were shooting to finish those 22 episodes. Typically, networks have much tighter deadlines and they're often very inflexible. So Westworld, the one thing that was kind of really unique, and which I think HBO in general is, there's a lot more shooting done before episodes get out the door. They shoot, you kind of sit with them a bit. I worked on episode 3, 7, and 10, and we were putting together cuts of 7 and 10 before 3 was even locked. Which, again, is not typical. It's more for premium television. It's not something that would be typical on a show on TNT or somewhere.

"...it's not week-to-week network, they would shoot everything out, and then after all of production, after they finished all ten episodes, then they'd start locking them."

Finding the right way to organize footage for your editor

Group clips, camera notes, and Scripter. One of the most crucial beginning tasks of the assistant editor is to organize the footage for the editor in a way that will make your editor happy to have hired you.

That means knowing your editor preferences, as well as following some general rules.

NFS: After you get the dailies in and everything is there, how are you looking to group the footage? And is that something you’ve based on your relationship with the editor you’re working with?

Reiss: For something like that, it's the editor’s call. Some editors only like the group clips in there, some people like the subclips and the master clips. Some people get really finicky about what color action is, what color stop or reset is.

I'll group things based on how many takes. If they shot four cameras for one take, I'll group all of those. My editor, Anna Hauger, only likes the group clip. But, for instance, a lot of editors like to see every single angle and then the group clip under it, so you'll have individual subclips of, let's say, four shots, and right under that you'll put the group clip.

Also, something that my editor likes, which I think is smart, when I set up the bin, I set it up in chronological order. Sometimes there's a shot that's clearly supposed to be an opening shot but it's Take F. So I'll put that at the very top of the bin. If there's a shot that's clearly meant to end the scene, but it's Take A. I'll put that at the bottom of the bin because at the end of the day, it helps Anna more to know what shots she's looking for in the story as opposed to Take A, B, C, D.

"Also, something that my editor likes, which I think is smart, when I set up the bin, I set it up in chronological order. Sometimes there's a shot that's clearly supposed to be an opening shot but it's Take F. So I'll put that at the very top of the bin."

But the one thing that editors all usually like is their clips grouped, and I do that based on the setup. So if setup A has four takes on three cameras, each group clip will have those three cameras, and you'll see the four takes. That's where I can add things, like, let's say they shoot it MOS, or sometimes as I was talking, you know, something rolls out, if there are four takes but three doesn't have B cam I'll name the clip, you know, Scene 20A-3_noBcam. Just little things for Anna, when she's working with the director, she isn't being like, "Oh, is there a B cam here?" She kind of can see it straight away. We have that short hand.

"...one thing that editors all usually like is their clips grouped, and I do that based on the setup. So if setup A has four takes on three cameras, each group clip will have those three cameras, and you'll see the four takes"

NFS: Then after that grouping happens, Anna knows exactly how to get started.

Reiss: She can just start watching. Something I should also say, I go by the script notes as well. When I'm grouping the clips, we get camera reports and script notes, and those are sort of my two road maps because on the camera reports I'll see, okay, shot A has four takes. It has A cam, B cam, and C cam, and the script notes will reflect that as well.

Sometimes, for instance, a script note has four takes but the camera reports only have three, that shows me where a discrepancy is and I can be like, "Oh, wait a minute. What happened?" And usually, on the camera reports, it'll say “Roll Out” or “Magazine Jam” or “we went to light another setup”, so and so forth.

They also do this thing where it's squiggly if a line is off camera and it's straight if a line is on camera. There's a program called Scripter, which is essentially the script notes within the Avid program. I go through and I bring in each group, and you can click on the line that can correspond to a certain point in the take, so that way Anna can open up the script in Avid, not a paper form but actually in Avid, click on a line like, "He killed my father," or whatever, and she can see every take just by clicking. See can see little stick marks, so if the director wants to see every line reading for a certain line, she can just go click, click, click, click, click, and there they are.

NFS: So then Avid is what everyone is using for this show?

Reiss: Yes, definitely. Particularly, on a show with multiple editors, the thing Avid does better than every other program is sharing.

We each use the same project, but only one bin could be open at one time. So let's say Anna has the current cut open. I could go in there, I can't make any changes to the current cut but I could lift, copy, and paste a section, open it up in my assistant bin, do some sound work or visual effects for her, and then we have a transfer bin that's just called, "For Anna," where I'll throw things in there and then she can open it up when she's ready, take a look at it, grab it. Avid is, by far, the best for sharing with other editors and their assistants.

The Jim Jeffries Show was on premiere, I know definitely Atlanta cut on premiere. It’s more prevalent, certainly, but I'd say Avid is still industry standard.

"Particularly, on a show with multiple editors, the thing Avid does better than every other program is sharing."

How to work around complex VFX sequences without VFX

On Westworld, like most show, you have to lock the edit, and later the VFX are made. Showing a cut to HBO executives with the text “crazy thing here” is enough sometimes, but more often than not, you have to learn how to convey the visual effects without ever having them.

NFS: Westworld has plenty of complicated effects. Do you create temp VFX, and how does it work in the edit with that?

Reiss: We would start getting some temp VFX pretty quickly. There are some things that are super complicated, and sometimes people will bring in the storyboards. For instance, on Episode 3 with the tiger, there was a banner that literally said, text on screen, "VFX, tiger runs at this character." Any of the real big VFX, we would use Previs, like the storyboards. It's difficult for an editor, but sometimes they just cut a shot and it's just the backplate. It looks like trees in a field and they'd, in their mind's eye, see a tiger running through it and figure out how long to hold it. It's definitely a skill that needs practice.

For instance, on Episode 3 with the tiger, there was a banner that literally said, text on screen, "VFX, tiger runs at this character."

Other times, I could try to get it as close as possible. For instance, throughout Westworld, the characters do a lot of stuff on tablets when they're programming ‘hosts.’

Because I came on Season 2, they had all the tablet elements on Season 1, so I could go in After Effects and essentially just place them. If I wanted to see an alarm going off on a tablet, I could go somewhere in Season 1, see the element where they used an alarm, and essentially put that using After Effects or sometimes Avid, using their tracking tool. I would do those temp VFX until they eventually got farmed out -- but that's only after the cut is locked.

So we did the temp VFX as we were doing our offline edit before we'd lock. If our VFX team had time, they would help us out. Or we'd go in using After Effects or Avid and paint out a boom mic or create temp muzzle flashes or blood spurts. Just so somebody knows if you got shot in the head or the chest, or things like that. That was a lot that assistants would do. We had one assistant on Westworld who was an After Effects wizard, there’s always one, and he'd be the guy where we're just like, "What's the quickest way to do this." Mark Allen Wilson is really a stud at it and helped us out.

If we could get it pretty close, then we'd put it in. It helps the network see it as they're watching a rough cut.

"...it's just the backplate. It looks like trees in a field and they'd, in their minds eye, see a tiger running through it and figure out how long to hold it."

Turnover: when the Assistant Editor becomes the most glorious middle-man

At the very end of the whole process, the place onlining the show cuts in VFX as they arrive, and then final sound mix is done. The end. But well before that, a million things need to happen. And it’s Yoni Reiss’ job to make sure those million moving parts are integrated through good communication.

NFS: Near the end of the process of finishing an episode, what happens? What's the last thing that you're there for?

Reiss: We locked the picture. The first thing that means, essentially, editing stops and everything's locked, it's within time. That is really when a lot of the assistant work also comes through. A big part of it is called turnover.

Turnover is giving everything to everyone who needs it. The color house would do a process called Online, so we edited everything DNx 36, which is pretty common for TV shows. We still brought it in low res because if we brought it the amount of hours of footage Westworld had at high res, the server space would be five or six times as much space. 21 terabytes would turn into 120 terabytes real quick.

So we send out offline edit. Essentially, that's the locked cut. What I'd give them is an EDL, because it's Avid and they work on Avid, too, I'd give them a bin, and something called a video mixdown, which is essentially Quicktime, just so they have reference when they're putting together the final product they have a low-res version of what I was looking at and they would send it.

It usually took them probably like a week or two to assemble it, and then they'd send me back something called a VAM, which is a video assembled master. A VAM is completely un-color-corrected. It's just for me to check that they onlined everything properly, that they weren't missing a shot, that nothing was a few frames off, so on and so forth.

I would check the VAM against our offline edit. I'd turn the opacity down to 50% and you can see if they framed a shot wrong or if a shot was off or if they weren't lining up right. It usually looks a little blurry image, or you will see their head in two different places, and you're like, "Oh, that's wrong." Usually, they weren't that many mistakes, but every once in a while, it's like, "Oh, the shot is a couple of frames off," and so forth.

And then after the VAM was good, we give the okay to online and then they would start color-correcting it. And then concurrently, we had a visual effects assistant who's also feeding them visual effects. So after they're coloring it or as they're coloring it, they're getting different versions just because the visual effects still change after they're locked. Sometimes that does change color of sound if, like, they wanted to move a gun shot a little later or, let's say, there was one explosion and they wanted to add a second one or something like that, things like that do change for color and sound. So we'd send updates if there was a visual effect that they felt really affected it.

So typically, someone on set would record, let's say there are three characters in a scene. He'll mic all three of them up, and then he'll give me a track that's also a mix of all three, which is great for offline.

But for online, when they're really getting into the nitty-gritty, they're gonna pick the individual mics. But the nice part is, when you send the EDL and how they did things on their end on Pro Tools, they could recreate that. They would only see the mixed track in the timeline, and in Pro Tools they could recreate that, match it up to each individual mic because the metadata was sort of all the same.

And then we'd also turn it over to the composer, which is pretty easy. Another AAS, separate guide tracks, we'd give it to them with the music, dialogue and sound effects separated, so that way they could hear what music we used for temp, mute that, put their own in, audition it for people, which is standard. They call it "spit tracks", but it's sort of, when we deliver it to them it's not like, "Here's a Quicktime with the audio baked in." Instead, it's like, "Here's a Quicktime, here's all the dialogue, here's all the music, and here are all the sound effects." So they have more control on their end.

And, of course, everything has to be the same length, it all has to be named consistently, and just very organized for them. We put something called the two pop and the tail pop. A two pop is the 2 seconds before the frame, you just have a visual with the number 2 and no audio, and then you also do 2 seconds after the end of the frame just so when they're bringing everything in they can see it lines up really nicely.

While that was happening, we had a visual effects team editor and a visual effects assistant editor who were turning over all of the visual effects and they'd be the ones that, when they'd get different versions in, they would cut them in, they would show them to the showrunners, they would take notes and so on and so forth, until they got those locked in.

NFS: Dang! There are so many moving parts that you oversee.

Reiss: Absolutely a lot of moving parts. Because again, when they have money, there's a lot of really talented people working on this, and definitely, as an assistant editor, part of your job is to sort of shepherd the materials to everyone who needs them. I have a great team, but with that comes coordination and making sure just everyone is on the same page.

"...doing odd jobs or sometimes Ubering, after 3-5 years, everyone I know has been able to get there feet under them."

If you can find a way to afford living in L.A. for long enough, you can make it

According to Reiss, while it’s a tough industry to break into, there is a lot of TV being made these days, and a dire need for Assistant Editors who know what they are doing. The mantra for Reiss is plain and simple: survive long enough catch a break.

NFS: Considering you’re path to Westworld, and now Watchmen, what’s your advice to others?

Reiss: I think something that they won't tell you in any film school is, the beauty of this industry or how to make it in this industry, in my opinion, is to survive. I've seen a lot of people who, particularly, I live in LA, have been here eleven years now, who've had a rough go of it, but if they manage to hang around doing odd jobs or sometimes Ubering, after 3-5 years, everyone I know has been able to get there feet under them. Some are very successful, some are kind of, but everyone is sort of having a nice, normal adult life.

"...something that they won't tell you in any film school is, the beauty of this industry or how to make it in this industry, in my opinion, is to survive"

LA's an expensive city, the industry, because it's make-believe, sort of closed off. I definitely believe, if you can hang around long enough, you can make it. Dan Kuba, the post-producer who hired me on Brockmire, hired me the next two times. I had 8 interviews to be in union work, and it felt for a while like, "Oh man, maybe I can't break in." But once you do, it's remarkable how quickly you're on the treadmill. I got Watchmen because I'm working with my same editor, Anna. It took a couple years until I circled to HBO, but once I got in, it's just like, "Oh, that's it." You sort of cross that divide. In LA, because it's expensive, it's not the easiest city to move to, if you can find a way to survive and make ends meet for the first few years where things will get a little weird, you'll get an opportunity.

And particularly now, there's a lot of TV being made these days. There are all these streaming services are coming out. Just in terms of content, a lot of it's being made. So there is a lot of work. I definitely believe, especially for assistant editing, something that's not taught a lot, there's a need for people who know what they're doing. And because the industry turns over so quick, even a successful person is looking for work once or twice a year, there are opportunities and things get weird with it if you hang around. My first union gig, I heard about it on a Friday night, I started Monday morning, just taking over for someone. It’s a high turnover industry, and if you hang around long enough, those opportunities will come in. Survival. That's really my big word. Find a way to make those ends meet, to save that money, to hang around just long enough, and I really believe the ones who can stick it out, if they're talented, will be justified.

"Find a way to make those ends meet, to save that money, to hang around just long enough, and I really believe the ones who can stick it out, if they're talented, will be justified."

I think also I would say, there are a lot of things I didn't know how to do, particularly on After Effects, that I can look on YouTube these days. Like No Film School, you guys are a great site, I think there are more and more resources for people who have that inclination to do it on their own. I remember when I got to AFI, they gave me a book called Non-Linear Editing 4, which is essentially like an editing textbook, like, this is what a codec is, this is what timecode is. And now so much of that can be found on No Film School, YouTube, online. There were definitely times on Westworld where I had to do, say, a glitch visual effect or something and I'd literally just typed it into YouTube and you can see someone do it in After Effects. It's definitely a world where those resources are there for you to find it out.

Thank you, Yoni!

'A Different Man'via A24

'A Different Man'via A24 'Bodies Bodies Bodies'via A24

'Bodies Bodies Bodies'via A24 'Past Lives'

via A24

'Past Lives'

via A24