'Black Sheep': Inside the Production of this Oscar-Nominated Short Doc

A memory of discrimination, refocused.

Nominated for the Academy for Best Documentary - Short, Ed Perkins's Black Sheep recounts the story of Cornelious Walker, a young English black man who, after being unable to escape his racist surroundings, tried his best to associate and join them.

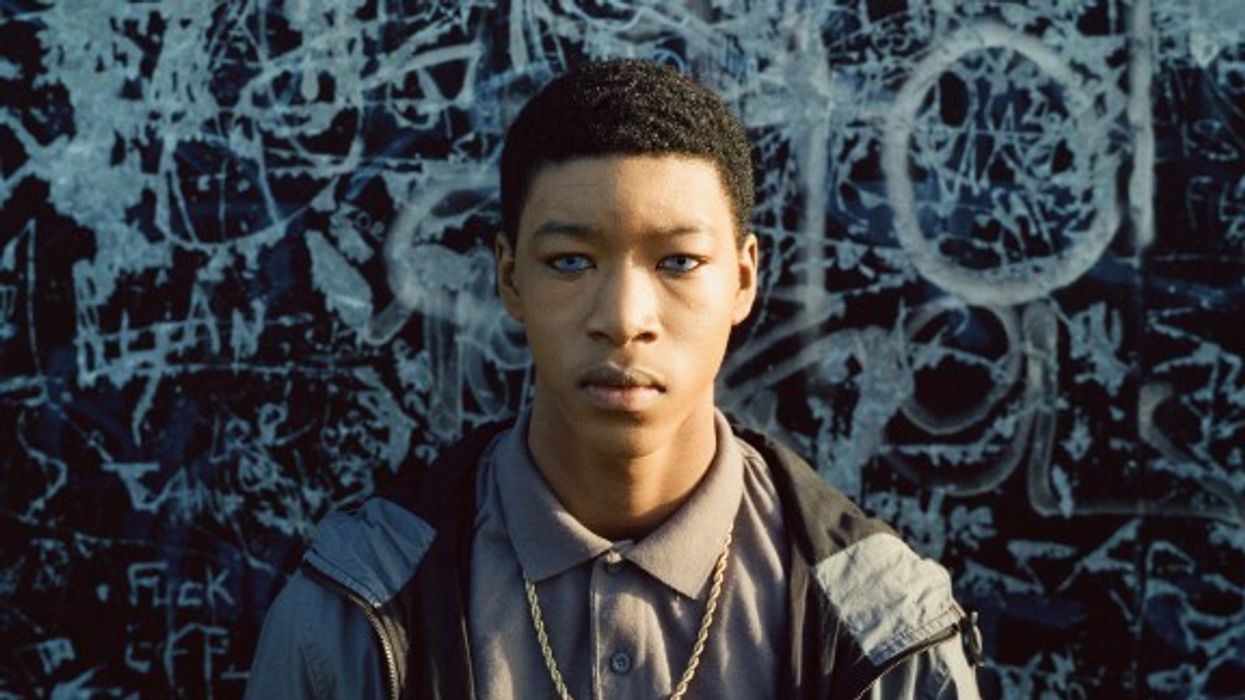

After a hate crime/murder hits too close to home in South London, the Walkers relocate to Essex in order for a better life. The only black family in town, the Walkers experience further discrimination from the white residents, leading to young Cornelious making the decision to bleach his skin, straighten his hair, don blue contacts, and change his accent in order to be welcomed by admittedly ignorant and racist locals.

Experiencing an acceptance that's both problematic and reassuring, Cornelious begins to dislike who he's becoming, even if it receives the wholehearted approval of his (white) peers.

Told via an interview with the real-life Cornelious and unique dramatizations of the story he depicts, Black Sheep is less a hybrid than a recounting of a memory. In its own way, it couldn't be more timely—culture appropriation has never been more hotly debated—and its straightforward approach refuses easy answers and a concrete finality. It's a merger of the recounting of a story and of being haunted by it.

As the 91st annual Academy Awards take place this Sunday evening, No Film School spoke with Perkins about the origins of the project, its intensely lit cinematography, casting, and how The Guardian helped to present the finely-tuned work. You can watch the film below.

No Film School: How did you first meet Cornelious Walker and had you known of his story beforehand?

Ed Perkins: Cornelius and I met through a mutual friend. We sat and had a coffee, and that was probably about a year ago. We talked about lots of things, including the film industry, and then I asked him about his life and a little bit about his story. With all of the charisma and bravery and honesty that you see in the film, he started to talk me through this extraordinary part of his childhood in the coffee shop, and I was blown away.

Especially in England, we're not used to people talking with such candor and charisma and vulnerability, straightaway. It was the first time I'd ever met him, and I was just totally taken aback with both his story and the way that he was able to express really complicated emotions and talk through what is a complicated, ambiguous story in a way that invited so much empathy.

We stayed in contact and became friends. I then asked whether he would consider allowing me and the teams at Lightbox and The Guardian to help him bring his story to the screen and share it with other people, and essentially, he said, "yes." I wasn't aware of his story beforehand, and I'm not actually sure how many people he's ever really told of what happened back then. But we got on incredibly well, and we really trusted each other, and we're indebted to him.

NFS: Was the concept for the project always for Cornelious to be reflecting back on his story with the accompaniment of dramatizations?

Perkins: Whenever you're thinking about how to bring these stories to life, you're trying to come up with an approach that is in service of the story itself, rather than the other way around. And most of the time, it's a discovery. The first thing we did was shoot an interview with Cornelius. We filmed over the course of two days in a little studio, and we were all very struck by Cornelius' rather extraordinary ability to tell his own story. He has a very distinctive look and very distinctive way of talking and with a huge amount of charisma.

We shot the interview with him looking right down at the lens, so that he was hopefully going to engage, us as the viewer, as directly as possible. It struck me after seeing that interview, that whatever other visual components we were going to add to the film, they had to be there in service of the story and never get in the way of the interview itself. And so, we wanted it to stand on its own as much as possible, and that's one of the reasons why there are lots of jump cuts to black throughout the film, which in early cuts some people thought was a mistake or representing things we were gonna cover up with B roll.

I felt very strongly that we wanted to give this film a real sense of transparency, and I wanted to show the audience almost like a sketchbook of how we made it, showing them where we cut in interviews, so that they're experiencing Cornelius as close to how I was experiencing him in the room during the interview. The question was then, "Well, what else do we bring to the interview? Do we leave it just as an interview, or do we animate it, or do we do something different?" And we all, including Cornelius, talked a lot about how best to do that. What we came up with was what you see in the film, which is an attempt to, in a way, bring to life some of the really painful memories from Cornelius' past, but bring to life them in from of him, so that we're getting his honest natural "verite" reaction to being confronted with these painful memories from his childhood.

We went back to the actual town where the events happened all those years ago, and we found the exact places where the events happened. We actually found the house where he used to live in, and we got permission to film in there. We found the actual room where that used to be his bedroom, and we repainted it the same color it was when he lived there. And so, we spent a lot of time and care trying to bring that world...to bring his life as a 12-year-old, as a 10-year-old, back to life in the present day.

Apart from the wonderful guy who plays the younger version of Cornelius, everyone else you see in the film is not an actor. They're real young men and women who live in the actual town. We spent a long time getting to know them, explaining to them why we wanted to make the film, and why it would be great for them to try to help us. We're indebted to them, because they're not actors, and they took part in the process and really wanted to help tell this story.

You're getting a slightly different hybrid approach, which we found to be exciting, but that also had its challenges. We went back to the place that holds very painful memories for Cornelius, and he was forced to confront those memories right in front of himself, to look at himself age 12, being hurt or being sad. I know that was difficult for him at times. There were times during our chat when he would say, "I just need to take a bit of a break and take a walk." That was part of the process, and it was something that he and I agreed to go on, that adventure, together. I can't speak for Cornelius, but I hope that there was a sense of catharsis in undertaking the process in that way.

NFS: There are moments during the interview portions of the film where your voice is heard asking questions off-camera. What was the most difficult aspect of conducting this interview? Was there much Cornelious wouldn't reveal?

Perkins: Of course. With any documentary, it's often the most painful bits of someone's story, and the bits that are hardest, that are also most revealing of the truth of someone's story. I think what was incredibly important in all of our films, but especially this one, was that Cornelius and I spent a long time getting to know each other. We met quite a lot before the interviews and talked through his story, and I had a good sense of where I thought the half of the story was before we sat down and actually did the interview. But we gave ourselves enough time to really explore other themes and issues.

As the director, it's imperative that you're open to the interview going into different directions, into places that you couldn't have expected and following the truth. There are always times where it's difficult to ask the followup question, or to prod, but that's all built on the relationship between him and I, of trust. He knew that I was asking those questions because I felt it was important to tell the story. He also knew that he was in control, and if he didn't want to answer a set question, that was absolutely his and everyone's right. That level of trust is crucial.

Together we worked through it and found what we thought were the most important things. People's lives are complicated, and one of the challenges in making a film is that, in 27 minutes, you can't tell every part of someone's story. You can't introduce every nuance and theme. Part of the process of editing it is to choose the things that feel most trustful, that feel most salient. I hope we've managed to do that in this case.

"When I'm making that initial string, I only have the interviews. When you're cutting that interview, inevitably you have to cut to black. The traditional way would then be to cover up those cuts with more footage, different footage. But I don't know, I really started to like the cuts to black."

NFS: When the film often cuts between scenes, we first cut to a black screen to provide a momentary sense of calmness. What did cutting to black provide for the pacing of your film?

Perkins: The way I tend to work when we're doing films like this is I'll always shoot the interviews first, and I'll then edit the interviews into a timeline, which I can essentially string out. And in this case, specifically, the basic structure of the film didn't change very much when we then went and filmed the other part, the other footage, the original footage, back in the town.

When I'm making that initial string, I only have the interviews. When you're cutting that interview, inevitably you have to cut to black. The traditional way would then be to cover up those cuts with more footage, different footage. But I don't know, I really started to like the cuts to black. I hope it gives the audience the chance to see or experience Cornelius as I did, and I wanted to be transparent. I wanted to show our hand. I wanted to clearly show audiences where we're cutting away from the interview and where there are cuts in his testimony, so that this is as truthful and as authentic as possible.

Clearly, that also helps with structure and pacing. But we weren't quite sure whether it was going to work, and I was a little bit nervous. It's obviously been done in films before, but we took it to quite an extreme level. You're always nervous about how people are going to respond to that, and whether they're going to watch and say, "Oh, God, it doesn't feel finished. There are all these holes in it." It definitely took a little bit of tweaking, but I'm pleased we went with that approach, and it feels right for the story.

"We didn't want to overplay that as a technique, but those moments that you do see are totally authentic, and I think add something else, something different."

NFS: At what point in production did you choose to incorporate the older, real-life Cornelious into moments of the dramatization? He appears slightly ashamed for whom he had become as he oversees his younger self interacting with the white teenagers.

Perkins: Well, that was always the potential reason for going back to the actual place (to bring to life these moments that Cornelius is talking about interviews), to bring back these memories to life, these painful memories, and then be able to film Cornelius' natural reaction to having those memories play out in front of him. That always felt really central, because I think, when Cornelius and I talked, he hadn't been back to that area for a long time, and it clearly held ghosts from his past and held these very painful memories. We thought it was important (and he thought it was important) to go back there and confront some of those memories.

We suspected that his reaction to seeing these memories would be interesting and would add another layer to the documentary. That always felt central to the whole approach. Clearly, there were lots of other moments that we filmed, and we had to choose which moments of Cornelius we put into the edit. We didn't want to overplay that as a technique, but those moments that you do see are totally authentic, and I think add something else, something different.

NFS: The film alternates between colors of piercing blue (to match the color of Cornelious' contacts) and firey red (as in being placed underneath a street lamp as a vicious fight takes place). What conversations did you have with your cinematographer about how to light the film?

Perkins: We worked with an incredible cinematographer, Michael Paleodimos, who worked on a short film called Stutterer, which won an Oscar a few years ago. He was extraordinary and the collaboration was amazing. We did talk a lot about colors. Clearly, those contact lenses were the inspiration for that strong blue color that we followed through with some of our lighting choices. I've always been interested in that rusty orange color, and our costume designer, Sharon Long (who is amazing) [found that] rusty orange jumper that young Cornelius wears in some of the scenes. Those colors started to take hold of our imagination.

In terms of the lighting, it was pretty high key lighting in places. There's a lot of handheld camera work. I didn't want this to feel like we were trying to in any way to pretend that this was real footage (rather than original footage shot by us). I wanted it to have that slightly heightened color palette, so that they are clearly memories, imagined memories, rather than anything else. As a result, the saturation in certain parts is quite strong. We worked a long time on the grain, trying to create a distinctive look and adding film grain on top, just to make those moments feel heightened, like memories. I spent a lot of time thinking about when we remember something, when we have memories from our childhood....what form do they take? What colors?

At least in my memories, certain colors (one, two, three colors) will often pop. They're the things I remember, or it might be a smell, or it might be music. These kind of strong textures are the things I remember, rather than seeing it playing out in long form. It's the same with camera angles. When I have memories from my childhood, I don't tend to remember things in mid shots. I tend to remember things like the very close-up details, or very wide shots of landscapes and places.

We tried as best as possible to choose camera lenses and angles that followed these very close macro textures, and then also stepping right back with a wide lens as well. It's all in an attempt to suggest that these are memories, heightened memories, of his past.

"Narratively, this isn't a film where we wrap things up in a neat bow."

NFS: Did that also affect the musical score for the film?

Perkins: I think the music is a huge part of the storytelling in this film. We were lucky enough to work with an amazing composer, Tom Barnes, and then also to be able to use some music from an Italian composer and an American composer duo, and that helped so much to bring this piece to life. You're always thinking about what kind of music and what tone you want to bring to a piece.

Especially with the sound design and music, I wanted to create a film that felt quite...the word we used in the edit was "angular". The music would be unexpected and it would take you to odd places and would come in very sharply and disappear quite sharply and upset the rhythm of the piece. As soon as you felt, as a viewer, that you were getting into the piece, or starting to feel comfortable, a big music cue would come in, or something with the sound design that would take you somewhere else and never quite allow you to settle, never allow you to be totally comfortable.

It's In the same vein of when Cornelius was going through these horrific experience. He was also constantly never comfortable, constantly looking over his shoulder, constantly worrying about where things were going to come from. And so, that was the attempt there, and we wanted to follow that through right to the end.

Narratively, this isn't a film where we wrap things up in a neat bow. The ending is purposely, consciously unfinished and unsettled, and that felt right to us. Cornelius and I talked a lot about that, and it felt correct to leave it on that haunting unfinished note and force viewers, force audiences to take the story home with them, to be confronted with the issues that Cornelius so bravely brings up, and not let us, the viewer, off the hook.