Capturing Jamaica on Different Film and Video Formats: Khalik Allah on 'Black Mother'

Acclaimed documentarian Khalik Allah returns with a studied rumination of Jamaica.

A visual prayer, a cinematic tone poem, and a familial elegy, Black Mother is the latest from photographer/filmmaker Khalik Allah, a visual artist whose unobtrusive quest to find new filmic layers is at once avant-garde and humanitarian.

Bursting on the scene with his riveting Harlem-set Field Niggas in 2014, Allah became the subject of many a'gushing newspaper profiles and academic pursuits. For his second feature, Allah decided to go back to an earlier short, KHAMAICA, expanding on his family's roots.

Set in the Carribean island nation of Jamaica, that feature, Black Mother, follows the men and women who make up the community, not the least of whom are often discarded and ignored. Whether dabbling in prostitution or other innocuous but dangerous conquests, the subjects of Allah's camera are less a representation of the entire nation than they are a memory of those who often don't receive a chance to speak. Told over a pregnant woman's three trimesters, Black Mother is Jamaica as both anthropological study and personable hangout.

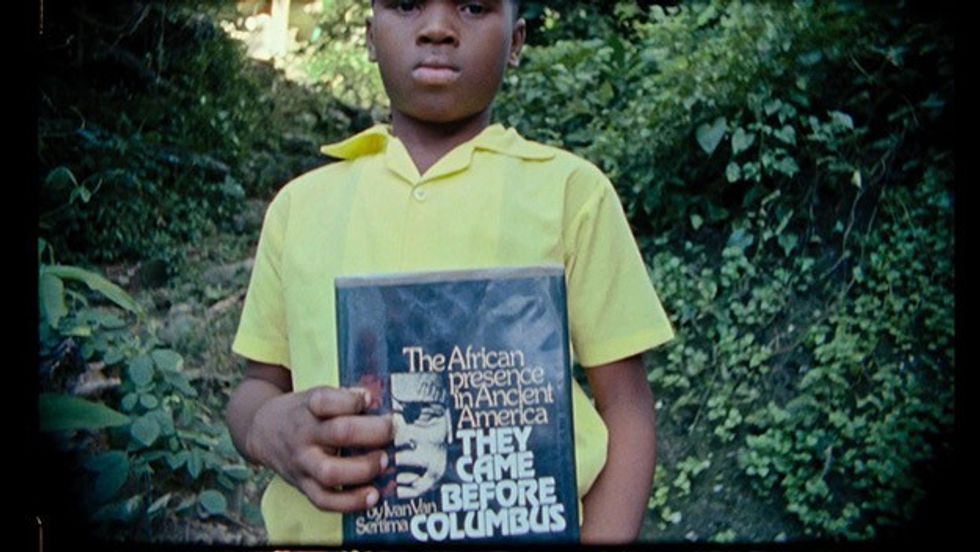

Black Mother is also an inspiring collaboration of visual formats, a prodigious example of the merger between digital and celluloid. When one young boy, late in the film, is shown holding a Bolex camera, his eye gracefully pointed at the viewfinder, a feeling of inspiration washes over you like the tides of the ocean that make up one of the film's very sturdy visual metaphors. Allah is never without a camera, and his portrait of Jamaica, at once graphic and restrained, is unlike any other you're likely to currently find.

As Black Mother gets set to open in theaters this week, No Film School spoke with Allah about his shooting and editing style, his career trajectory, and how his grandfather inspired his initial pursuit of the island nation.

No Film School: The last time we spoke on the record, back in 2015, you were releasing your first feature into the world. Since that time, you've released a book and a second feature. What has that process in the interim, between features, been like for your career?

Khalik Allah: Well, a lot, a lot of good things. The thing is, after I filmed my first feature, Field Niggas, I uploaded it to YouTube on September 28th, 2014. I threw it on YouTube and by January of 2015, which was just a few months after that, I began shooting my second feature, Black Mother [in Jamaica]. I didn't have a title for it at that time.

When I came home from Jamaica in January 2015, that's when Field Niggas started blowing up and people started asking if they could take a look at it over the internet (the True/False Film Festival advised me to take it down) and so then I started traveling with it.

I tell people that I was working on Black Mother for three years, from 2015 through 2018, but really a year-and-a-half within those three years I was just touring Field Niggas around. I was technically working on Black Mother for a much shorter time [than three and-a-half-years] and so there was a lot going on with my career because Field Niggas had put me on the map. I was doing shows, I was doing screenings, I started doing photography exhibitions, I had a book published, etc. So much was going on around my name, that I had to allocate time so I could get back into the production of my film.

NFS: Did your short, Khamaica, influence your starting up Black Mother?

Allah: Khamaica was actually released the June before Field Niggas came out. That was way before I ever knew I was going to make Black Mother, that goes way before I even knew I was going to make Field Niggas. Some of the footage in Khamaica made its way into Black Mother, actually. Because I had so much material from my childhood, and from the different ties that I had in Jamaica, I was able to lean on some of that material and incorporate it into Black Mother.

NFS: Where did your love for the power of nondiegetic sound come from? What do you think it provides your work with?

Allah: I believe it gives me the ability to be more poetic in my approach, to be more meaningful. Sometimes in the lack of direct meaning, you find more meaning and it's indirect. When it comes to a documentary, I think that's useful because this is not supposed to be the definitive truth.

When you take a picture of a place, it's just a snapshot and the picture itself is never the truth because there's so much that wasn't able to be captured into the frame. You have stuff that's just outside of the focal length of the lens that isn't rendered onto the picture. In that sense, when I make a film, it's just a sample. It's not necessarily the full truth, it's just a sample of the truth and then when you have the out of sync audio of the video, that hints at that and makes the audience listen and see and form their own association between what they're hearing and what they're seeing. In that way, it invites them to find their own truth. It's a device.

"My work is very much about taking people with me to an environment that they maybe wouldn't travel to."

NFS: Do you experiment with the levels of sound? Whether it's a child laughing or an adult explaining their experience to you, the impact of volume (both loud and distant) cannot be understated.

Allah: Oh yeah, definitely. There's a use of different textures, use of different colors, and there's variety in the experience. Especially in the theater, when you're watching in the theater and you hear these different levels, none of them are too blown out and none of them are too low but it gives you an experience of space and time.

My work is very much about taking people with me to an environment that they maybe wouldn't travel to. In the case of Field Niggas, yeah, that's New York City but in a part of New York where the average New Yorker doesn't even go.

In the case of Black Mother, yeah, this is Jamaica, but it's way out of the tourist realm, and so many people that would visit Jamaica would never hit many of places that I touched on in the film. I use the audio and I use the levels as another technique that hint at space and time and also to add a roundness in the texture and the quality of what you're hearing and also what you're seeing. Just like the visuals have many different formats, different format cameras, the audio, although it's on the same audio device, it has different levels, it has its own different textures which are supposed to complement, or are complementary, to everything else.

NFS: There's a way in which your two films ruminate on the unwavering perseverance of the human spirit. But it never does this in a blatant, "Issue-oriented" presentation. How do you find the positive in occasionally dire situations?

Allah: Well, I studied psychology and one of the main things that I've learned is that we are responsible for what we see. It doesn't seem that way, it seems as if we're representing what we see and what we see tells us what it is, but in fact, we tell everything what it is.

We give everything the meaning that it has for us. No matter what we're looking at, if you look at it with vision, it becomes healed and holy. If you decide to look at it with vision (and vision is different than seeing, it's heightened, more beyond the body's eyes) and you look through the body's eyes, you look almost through the demon's eyes, which is always dealing with separation and judgments. But when you look at it from a more aerial perspective, which would be a spiritual vision, then you begin to see the meaning and the light and the peace even in the most dire of circumstances. Because it still exists there. Sometimes it's just covered up, it's covered up by garbage and dust and waste and all sorts of things which need to be moved out of the way in order for the light to shine on it.

For me, I'm always making a conscious effort to show that peace is a conscious decision. Peace is a conscious thing. It doesn't just happen. it needs to be consciously decided, chosen for. When I'm working, I'm constantly trying to elevate and purify my vision in order to see the light in all things and in all people.

My subjects really react to this because it's almost a form of charity to look upon them as if they're extremely forward in their own development. They've already progressed to their graduation, in a sense. What I mean is, I see them beyond their circumstances. I see them beyond their current life situation that they find themselves in. I try to look upon them as if their bad circumstance, which seems dire, is actually just nothing. It's just another experience for them, it's a small thing that they have to go through to get to where they're really going.

"All of these different formats were to capture the fabric and the different texture of Jamaica. It's a very stylized, textural place."

NFS: Where did the choice to shoot Black Mother on both film and digital come from? Were you looking for a visual contrast or companion, if you will?

Allah: Had I shot this entire movie on film, it may have looked like the thing was shot in the 1970s or in the 60s and I felt like keeping that hot quality, digital HD footage keeps it fresh. It lets people know that this was shot yesterday, that it wasn't shot in the 70s; this will be brand new, it's fresh.

The idea was to display my range as a photographer. I'm the type of director who shoots all of his own material and I take pride in that. I have a degree of fun doing that. So because I have a budget and because Rooftop Films got behind this film and gave me the Technological Cinevideo Services Camera Grant, I was able to use so many different camera formats. Shoutout to TCS and shoutout to Rooftop Films and everybody at Rooftop for giving me that TCS Camera Grant because I was able to use the Bolex and a Super 8 camera and digital cameras and a drone.

All of these different formats were to capture the fabric and the different texture of Jamaica. It's a very stylized, textural place. You go to Jamaica and you look at how a person is dressed. A lot of people who are crazy stylish, even if they're just doing some sort of like construction work even....you know, you'll find the trash man looking really fresh and all he's doing is picking up trash. Jamaica has all these different textures and the different camera formats allowed for me to play on that.

NFS: I wanted to ask you about the framing. What does the 16mm image, the actual look and feel of it, provide for your work? There are times in Black Mother where the bottom of the screen features another (or the next) image in the sequence, peeking out just underneath the centered image, as if the projector can't wait to get to what's next.

Allah: Good question man, I appreciate that. A lot of people that work with film, 16mm or Super 8, would probably crop that out. A lot of people would say, "Oh you know, that looks sloppy" but I felt it necessary to incorporate, to include that in the film because...this is raw.

My work is known to be unpolished, extremely raw, and the thing is, I was trying to show the full picture of Jamaica, and so by using the full frame, it was just a play on that. It was just another metaphor for the complete conclusion of 360 degrees: the positive, the negative, the neutral, the profane and the sacred, and I don't wanna crop anything out, even if it was at the risk of making the film look sloppy to a degree. I don't think it was sloppy. I like it like that. I think that adds more style to the whole thing. That was the idea, to show the full frame, the full picture.

NFS: There's a line in the film about the plethora of churches found throughout Jamaica and how that was predicated on the amount of slavery in the nation. Could you elaborate on that?

Allah: As you can see, the film is broken into three trimesters and a birth. There are really four parts to the film, so this film is like the heart, because like the heart, it has four chambers. It wasn't a cerebral project. This project came from the chest, it was a heart project. So using those four parts really helped me to decide and frame my editing.

In that first trimester, I'm doing certain things like establishing the church. I understood that the film was going to have a very spiritual depth to it. I wanted this period of exposition where we talk about the churches and later on, that would be in contrast to the deeper spiritual energies that come alive later in the film. My understanding is that the Jamaican people have a natural predilection to be spiritual. Regardless of the container of that spirituality, regardless of the religion. It could have been Islam, where instead of praising Jesus Christ, they may have been praising Allah. It could have been Catholicism they were given, but they were given their slavery, Christianity, which is actually an African religion but they didn't get it in that form, in its original Ethiopian form. They got it in a form which made them docile after it had been manipulated by Europe, specifically by Rome.

The whole idea was to set the film up so that we're going to make a distinction between the churches and the natural spiritual capacity of the people. I tried to do this film peacefully, where it didn't necessarily shit on Christianity or anything like that. Later on in the film, before the birth, there's a long prayer that's seven minutes long, and this woman who I had just met before...she prayed for me, she is going on about how she left the church, she doesn't go to church anymore, etc. I think there's a nice contrast there, but not everybody can pick up on that because this film is so dense.

It's similar to like when you get fed in Jamaica, when they give you a plate of food. That plate is dense. There are all sorts of yams and ackee and breadfruit and you get a lot of food on your plate and you don't have to eat it all, but it's there. That's how I made the film, I made it with a lot of options, a lot of themes. There's a lot of food on the plate and you may not like it all, you know what I'm saying? But it's up to you to decide what you want. Some people eat it all and they love it. Some people will only eat a little bit and that's okay too.

"This film wasn't made to be in competition or to be in the film world, specifically. That's the thing, us as filmmakers, that often times we get so embedded in the film world that we start making films for other filmmakers."

NFS: What was it like connecting with and filming your grandfather?

Allah: In a way, that was one of the main directions of the film because my perspective of Jamaica is very unique. I was born of a mixed race, being half Iranian/half Jamaican and on top of that, I grew up in New York not within my Iranian family but with my Jamaican family. I'd go to Jamaica and back to New York and then back to Jamaica my entire life, well, for my childhood at least. It gave me a very unique perspective. Had I been living in Jamaica my whole life and had been born and raised there, I probably wouldn't have made the film the way that I did, but because I had this unique perspective, I made it this way.

Many of those early trips to Jamaica were to visit my grandfather, to sit at his feet and listen to him. He used to give me prayers. The first thing I did when I went to his house, his maid would be there just praying over him. When I was 15, I was like, "Oh, this again?" but I began to notice the importance of it as I got older into my 20s. I wanted to make this film with a spiritual feeling. That was what I was really going for.

This film wasn't made to be in competition or to be in the film world, specifically. That's the thing, us as filmmakers, that often times we get so embedded in the film world that we start making films for other filmmakers. I'm like "no, I'm not making film for the people that are in this 'fellowship.' I'm not making this film just to be in universities or these really intellectual, theoretical people who are just soaking up film theory. I'm making film for everybody and for people that are way out in the world, certain people that are into meditation, I want them to be drawn to my film, certain people that are into yoga, I want them to be drawn to my film, people who are into health and the earth, conserving nature, I want them to be drawn into this film." That was the idea.

I think taking this approach to my grandfather kept it loving. There are some parts of this film that are harsh, I know, and may be hard for some people, but it was important that I be honest and that I don't just make it all lovey-dovey. I gotta keep it as it is because that's myself, that's me being me. I mean, I made a movie called Field Niggas...

NFS: Are you editing the material once it's been shot? Making an assembly once you have everything you need? What's your editing process?

Allah: Editing for me is a long process of organization. I organize and I organize. I have to get organized and as I'm organizing things, and it's more or less like I'm seeing what I have and I'm doing it as I shoot. In a sense, I had six hours of audio on this film. Throughout the years I was going [to Jamaica] and filming, I would take this audio, these interviews, these testimonies and put them up on a flash drive and would play it in my car. I'd connect it to the USB in my car, and while I was traveling with Field Niggas going through Massachusetts or going to Connecticut, I would just listen to all of this and start to organize it into themes. That's why I say a lot of this is just about organizing before I really begin editing.

There's a part about women talking about raising children and how children should be raised. What I do is: I take all of these women's audio and put it into a timeline on Premiere or Final Cut (I started off with Final Cut and then I had to switch to Premiere halfway through the edit because I upgraded my system).

I look at the audio like it's a gallery, almost as if I built a photo gallery, just with the audio itself. I put up the walls, the doors, everything....just with the audio, the audio was the complete structure. And then I came in with the visuals a little bit later. That part was like hanging the pictures up in the photo gallery. That part was a little easier for me. It's a very music video-esque style because a lot of doing music videos is when you're given the track and then you just put another layer on top of the track. So in a way, I created a long music video of a documentary...but without music.

Richard Gere and Uma Thurman in 'Oh, Canada' via Kino Lorber

Richard Gere and Uma Thurman in 'Oh, Canada' via Kino Lorber  Uma Thurman in 'Oh, Canada'via Kino Lorber

Uma Thurman in 'Oh, Canada'via Kino Lorber