Mike Wallace: When TV and Journalism Got Married

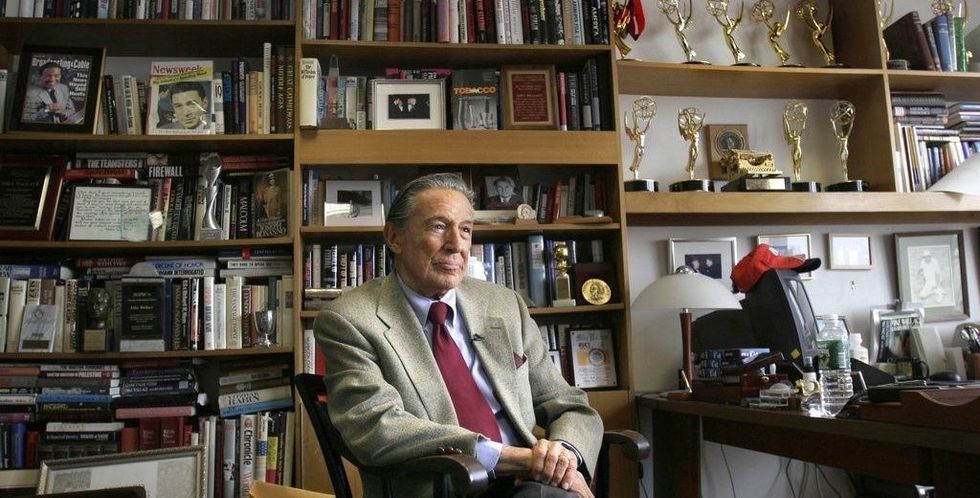

Avi Belkin's documentary, Mike Wallace Is Here, reckons with the legacy of the master interviewer.

Mike Wallace, the legendary host of 60 Minutes, changed the face of journalism and TV. That's a fact. And in this seemingly post-truth era, it's hard to separate fact from fiction. This both is and isn't Wallace's fault, as Avi Belkin so aptly illustrates in his engaging new documentary, Mike Wallace Is Here. Although Wallace was renowned for his investigative journalism, his relentless showman approach ushered in the sensational cadence that has come to dominate broadcast journalism today.

Consider this exchange, which occurs at the beginning of the documentary:

Bill O'Reilly: No, it’s not. You’re a dinosaur. You have to engage now! You have to be provocative. This is going to embarrass you, Wallace. You’re the driving force behind my career. They say I'm the most-feared interviewer since Mike Wallace.

Wallace's "gotcha" tactics were dramatic, and his charisma made for entertaining television. But as Belkin's film depicts, what Wallace was after was the truth. He wanted to hold public figures to account, to shine a light on their misdeeds. Often, he did just that; his reporting changed the public discourse around Malcolm X, the Watergate scandal, Vladimir Putin, and Big Tobacco, to name a few. He asked the tough questions and got the tough answers. The problem? The medium was the message. While the blurred lines between journalism, television, opinion, and documentary can be traced back to Wallace, he didn't espouse them. He simply set the stage.

No Film School sat down with Belkin to discuss the changing landscape of broadcast journalism, and how documentaries are filling the void.

"Mike Wallace changed the game. He was the revolution of television."

No Film School: When did you start making this film? With so much archival material, I can imagine it took quite a while.

Avi Belkin: I started three years ago. I don't think that there's a documentary that takes less than two years. It takes a while to kind of understand what you're doing and to find all the archive materials — a lot of searching and understanding what the story's about and how you want to tell it. Once you get there, then you go into editing. And then, in editing, everything things falls apart, and you start reconstructing again.

NFS: So your first order of business was to see what's out there, archive-wise, to try to craft a narrative?

Belkin: No, I think the first order of business is reading and just getting submerged in the subject matter as much as you can. I always start by researching everything I can find about [the subject]. Because in the beginning, you don't even know what you're doing yet.

My idea, in the beginning, was to try to look for a genesis story on broadcast journalism. How did we get here? How did we find ourselves in this clusterf**k situation in journalism? I always look for a microcosm story — through it, I can tell that much bigger story. So I was looking for some character or event that I could tell the broadcast journalism story through.

Mike Wallace was this unparalleled character in broadcast journalism. He had this career that started in radio, then went to television in the early days, then, obviously, 60 Minutes. Mike Wallace changed the game. He was the revolution of television.

"The questions we ask are revealing of our subconscious, of our own character."

NFS: How did you figure out the balance between telling a story specific to Mike and his life, and telling a story about this macro issue of broadcast journalism?

Belkin: I looked at all the interviews that he gave to people during his lifetime, and I transcribed all of them. That was kind of the framework that the film worked from. And on the other hand, there were all the interviews where Mike was the interviewer. I thought that was interesting—it's very rare that you have a person asking questions, but also answering questions. Being on both sides. It's a double portrait.

When he was interviewing people, I was looking for questions where he reveals his own character through them. We're always asking questions that are specifically of interest to us. A lot of the times, the questions we ask are revealing of our subconscious, of our own character. So, that was what was guiding me when I was watching the materials.

For the first time ever, CBS opened the archives for us. It was insane. I watched over 1,400 hours of 60 Minutes. It took a year. And during that time, you're not only going to gain an appreciation of Mike's craft — he was so good at what he did. But also, you get a sense of themes. You see these questions he's repeating over and over and over again. Like, for example, "How many times have you been married?" He asked that a lot. And Mike was married four times. He would always ask people, "When are you going to retire?" Mike retired when he was 89. So I looked for moments where he was basically showing, "This is Mike Wallace."

Belkin: The obvious thing, I would say, is that an interviewer who is good at his work is well-researched. He's coming to the interview knowing a lot. Mike was the master of that. He would work for weeks before an interview. I watched the first 15 minutes before an interview begins, which you never saw on television. You see Mike with a pile of pages, just reading notes. Then, during the interviews, he would go to his notes and would say, "On January 1962, you said this and this and this," and he would confront people with their own quotes.

But what changed the game — and I think it's unparalleled in anything that we see today — is the dramatic element that he put into an interview. Watching him do an interview was almost like watching a movie. Regular interviews can be very boring. I don't think people understand how boring they can be. But I never watched an interview with Mike and was bored. I watched all the raw footage — four or five hours sometimes — and it's all interesting.

"Mike was obsessed with people's weak spots. When a person is irritated, he's a bit more honest. He's deviating from the script."

I think that's because of Mike's character. Very early on, Mike understood that the way to get under a person's skin is to irritate him. And when a person is irritated, he's a bit more honest. He's a bit more vulnerable. He's deviating from the script. Because we all come with agenda: "This is the answer I'm going to give." And then when a person starts feeling a little bit uneasy, or a question rubs him the wrong way, he starts becoming less scripted. That's when the real color comes out. Mike was obsessed with people's weak spots.

I think that's another reveal of his own character. Mike was not a reflective person. He was always trying to gain more perspective on his own weak spots through other people's weak spots. So, he was a needler. You see in his interviews — especially in the outtakes — how he would always throw a little jab at people to try to get them unsettled to get some more truth to come out in their answers.

Belkin: There were a few, actually. Thinking about it now, they were journalists. The interview with Oriana Fallaci, the Italian journalist — she was the biggest journalist in Europe in the '70s and '80s, and was basically a female [equivalent to] Mike Wallace. She was very tough and did interviews with all the living people of the 20th century. That interview exchange was very equal. I felt like she was seeing eye to eye with Mike, and in many ways, knew all his techniques. She kind of knew what he did, and she was smiling throughout it, which was beautiful to see.

"Mike would always love to start with a killer first question."

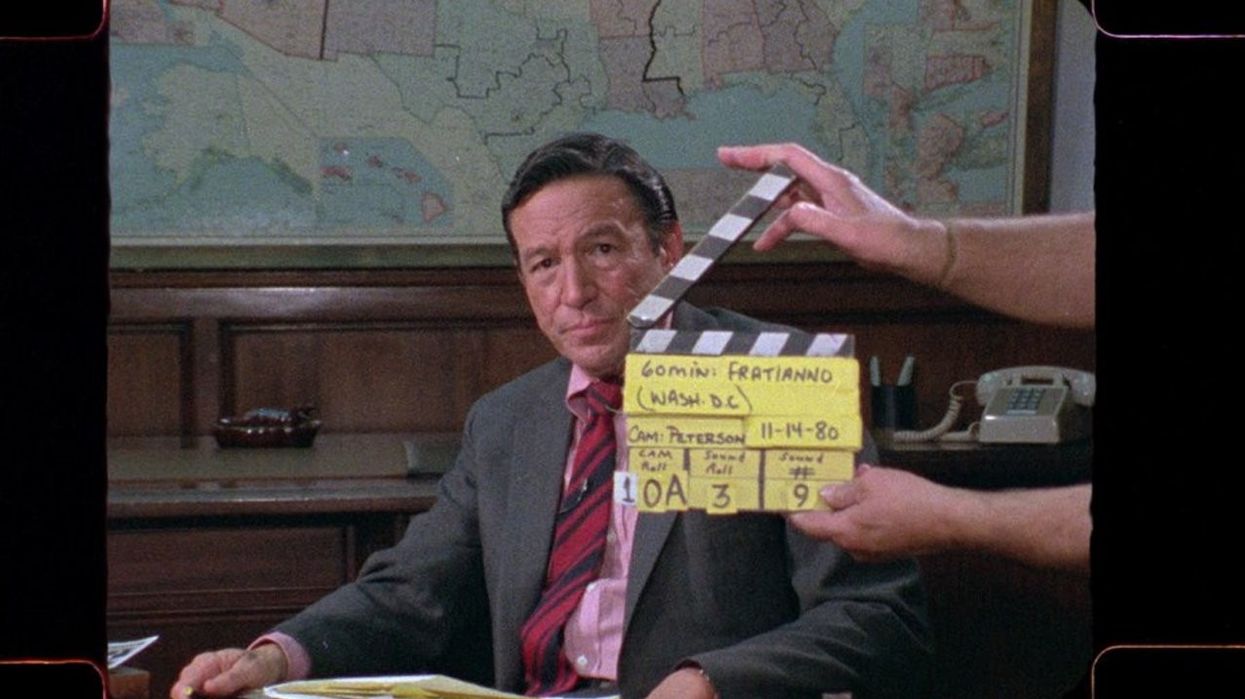

Mike did an interview with Larry King, which I felt was also very equal. But Mike gave Larry King all of his classic moves. Mike would always love to start with a killer first question. So, the first question that you hear when the slates are coming off, is Mike asking Larry King, "Are you nervous?" And Larry says, "No." And Mike says, "People say you're a patsy." You see Larry King really swallows. And then he's like, "Yeah. Yeah, I know."

And then they go into this exchange where Mike says, "Imagine you're interviewing Hitler. It's 1935 in Germany." So, these two people, who are so good at interviewing people. [these] legends of journalism, hypothesizing about what would it be like to interview Hitler. Larry's approach was curiosity. He would be like, "Why would you do that?" And Mike's approach was, "You did that" — telling him to his face what he did, and getting him to react to the facts of what he did.

A lot of the time, his peers were the only ones who really held a candle to Mike. Barbara Walters, I think, is the only person who really got Mike. So, in the introduction to the story with Mike, she says, "You can't do an interview with Mike Wallace without being Mike Wallace." And then she goes in and just rips Mike for like 20 minutes in a beautiful interview. And to Mike's credit, I think, he answered every question there. He didn't shy away from those. Although, sometimes in his life, he was hesitant to answer those honest questions.

NFS: When he was asked about his own marriage, it's almost as if he didn't see it coming.

Belkin: He was a little bit caught off guard, right? That's exactly what we talked about before. Those questions that you don't see coming — that's the moment where a person is really without his shields.

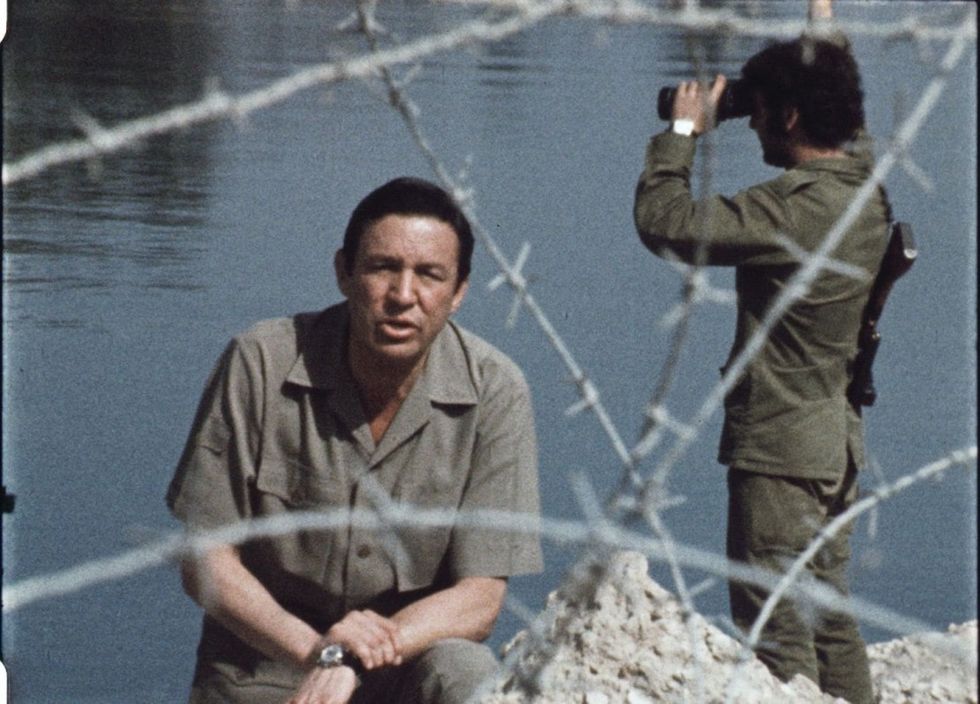

NFS: You could have gone straight archival with what appears onscreen, but I liked how you had different competing frames, at times. And other times, you could see a little flicker of a film strip. I thought that was a really interesting visual approach — it made the whole film feel more dynamic.

Belkin: I like those imperfections in the film and the archive materials. They feel physical to me. But also, this whole movie is archival, and I felt like in a way, it was Mike's subconscious memories floating into each other. Those little blips and splices that connect the memories that move you along from place to place, connecting our lives... that is the driving engine, visually, of the film.

NFS: I thought it was a really strong and interesting choice for you to open the film with that exchange about journalism versus opinion. That is kind the dialectic that we're dealing with right now.

Belkin: Beautifully said. That's the crux of the state of journalism today. We find ourselves today in a situation where we can't separate opinion from fact.

Belkin: It was already very much clear that journalism has shifted into opinion journalism. People who are not journalists are giving you this so-called news. We see it with comedians. Like, comedians today are journalists, right? Stephen Colbert, John Oliver...all those guys are basically doing news shows. Which is okay, and I have no problem with that, but it just creates a different kind of way of getting information.

Journalism's duty is to get information to the public. That's the journalist's role. How they do it, obviously, differs. Before Mike, it was very much objective journalism—very straightforward, Edward Murrow, Walter Cronkite... all those guys were giving you the voice of the establishment news: "This is how it happened." No spice.

NFS: Did you see Meeting Gorbachev? I interviewed Herzog for it. He told me that he sat down with Gorbachev, and to put him at ease, said, "Look, I know you've spoken to a lot of interviewers before. But I'm not a journalist. I'm a poet." That apparently just disarmed Gorbachev completely. I loved that.

Belkin: Yes. Documentary is art. Journalism is not. We shouldn't forget that the motives are different. Documentary is about emotion. And journalism should be very concrete. It should be more about the facts—giving information to the audience. I agree with Herzog.