Scorsese & De Niro: True Partners in Crime

Over 40 years of epic collaboration from cinema's favorite wiseguys: Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro.

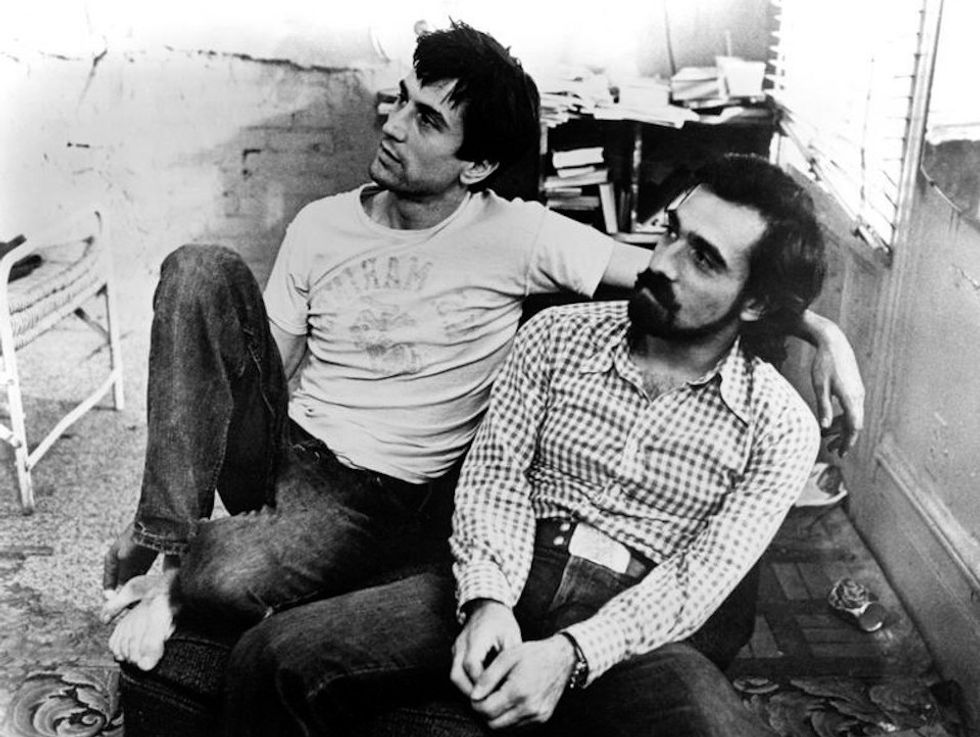

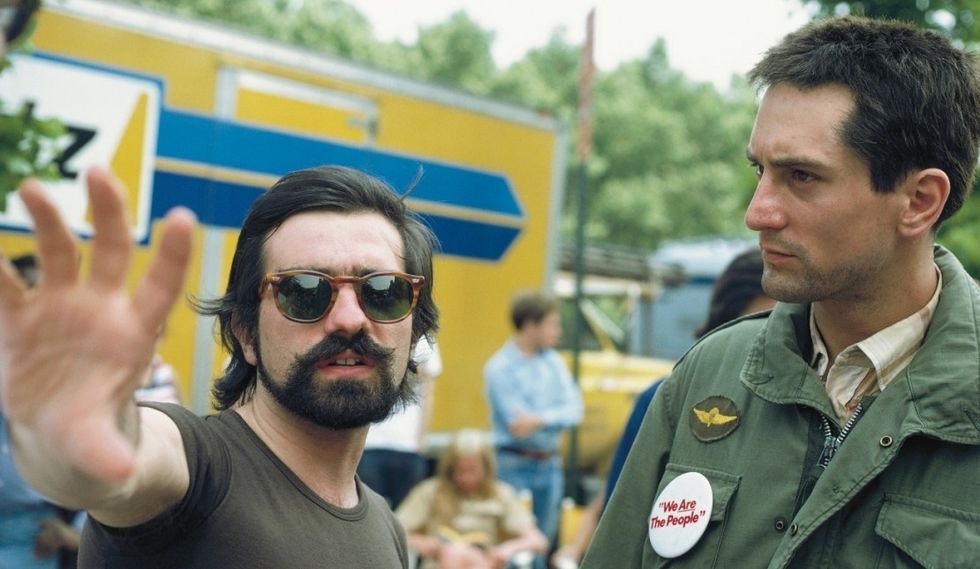

Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro joined forces at the Beacon Theatre for a Tribeca Film Festival master class: exploring 40+ years of collaboration from Mean Streets to The Irishman. Slated for a Netflix release this fall, their latest collaboration is a gangster epic with many of the usual suspects. The pair have their act down. Sprightly, bespectacled, Scorsese took the stage with a grin of childlike excitement. De Niro, known for surly, gabby characters, is the opposite in real life: onstage, he plays an introspective second fiddle to his pal Marty.

Together, they look almost regal: two icons who have reached overwhelming career heights. At the same time, they’re dwarfed by the massive vaudeville décor that surrounds them with gold: two human dudes, who started out just like us. That’s right, there’s hope. The great Scorsese started out as a nervous fan, too—a physically beleaguered young man who assuaged his fears with film and music. NFS is here to pass on his best life-advice.

Observe the World

Scorsese grew up a misfit, restrained by physical issues. “Because of my asthma, I couldn’t run around and play sports with the other kids. So I spent a lot of time inside,” the director recalled with a good-humored shrug. From age eight to 23, Scorsese lived in his parents’ Little Italy apartment, on Elizabeth between Houston and Prince. He spent much of his youth staring out of a window, studying characters on the street and the trappings around them.

“That view was the best,” Scorsese grinned, nostalgic. “I could always see everything happening in the neighborhood from above. Later on, critics would say ‘Oh he’s doing God’s point of view in his films,’ but no. That overhead shot came from my childhood,” Scorsese chuckled.

Another fortuitous by-product of asthma was Scorsese's immersion in American cinema. “I watched countless, countless hours of movies and TV. I didn’t come from a reading culture,“ he admitted, almost sheepishly. “There were no books at the apartment. So for me, it was all visual storytelling—a mix of what I saw on the screen…and in the street.”

Set Your Mood

But Scorsese wasn’t just a student of cinema. The third pillar of his film education was music.

“Music framed all my stories. Back in that little tenement apartment on Elizabeth Street, I found the most extraordinary state of freedom: whenever I listened to music, I kept seeing images.” He paused, reflecting. “The first music I heard was Django Reinhardt when I was four or five. It created abstract images in my head, and they’re still with me today. That was the beginning of my process.” Clearly moved by the memories, he tried to switch back to the practical. “That’s always been the way I start designing a picture. I listen to music alone in a room somewhere. The songs create images. They begin telling the story.” He shook his head, still moved. “Roy Orbison, The Drifters, they represent memories. These songs I use in my movies are more than nostalgia… This music is what scored our lives.”

Scorsese’s eyes glistened; he took a deep breath. De Niro nodded slowly: in many ways, Scorsese’s story was his story, too. Then, it was time for two film clips: the two old friends leaned back in their seats, craning up at the screen—still intrigued by their own work.

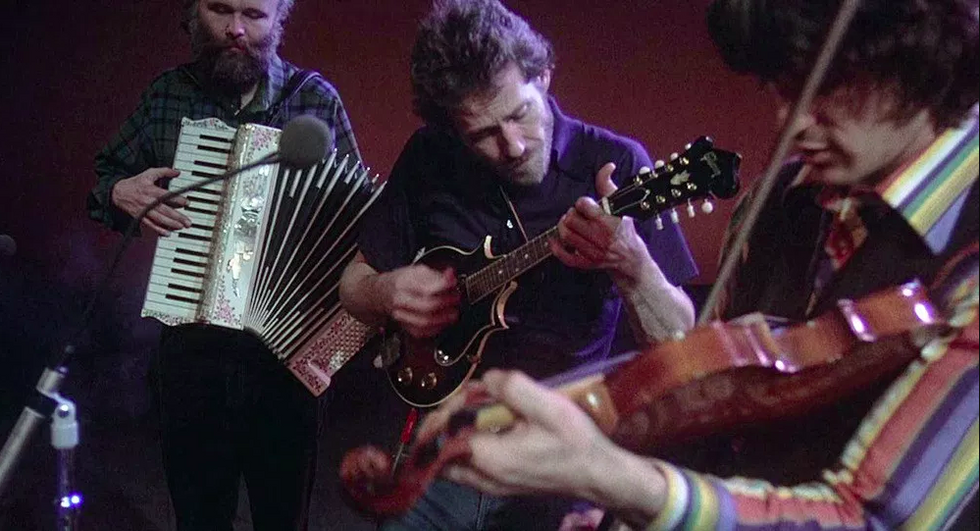

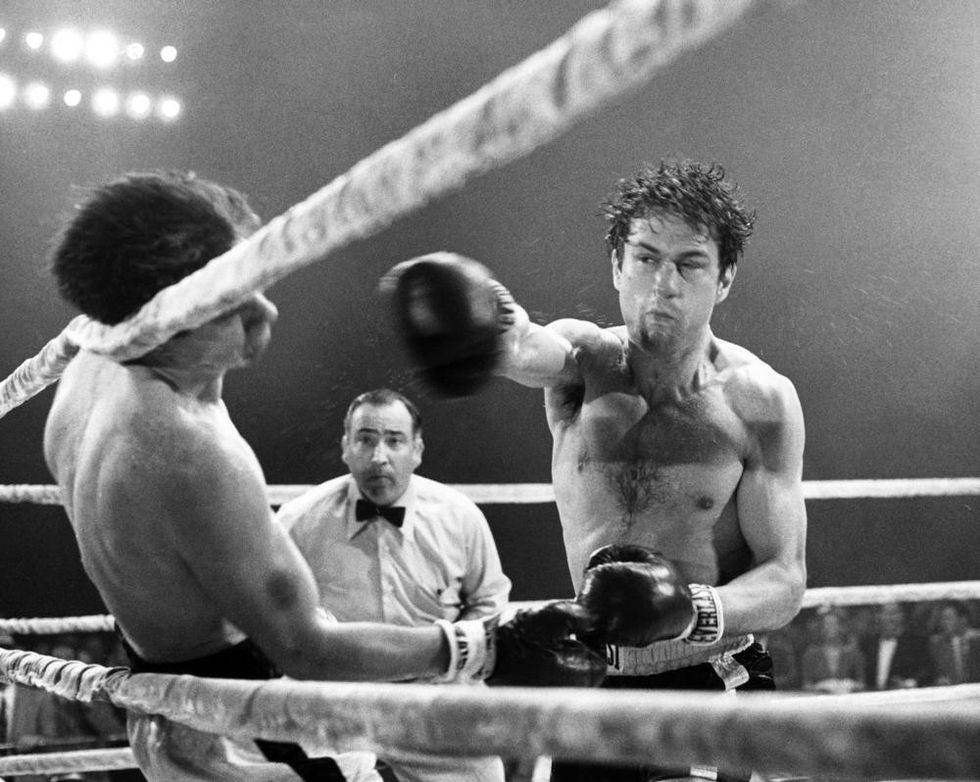

First came The Last Waltz, and a mesmerizing performance by Emmylou Harris: the camera floated around her and each musician in perfect synch with the music—a harmony both delicate and precise. Then came Raging Bull, and a brutal boxing match. Here, the camera danced in intimate close-up, scrutinizing every staccato beat of the fight. Both scenes felt dreamlike. When the lights came back on, Scorsese explained his two choices.

“I picked those two clips because they’re perfect examples of how music conjures images in my head for a scene. Before filming The Last Waltz, I did drawings for each song’s performance shot by shot, designed to go with the specific music.” Scorsese’s voice rose as he spoke, memories tumbling out almost faster than words. “It wasn’t a situation with seven cameras to be edited later; each shot was very deliberate. The tracking shot on Emmy-Lou Harris: that had to be straight, it had to have a direct feeling. It was the same for Raging Bull.”

And it wasn’t just pop music that moved him. For Casino (1995)—which turned out to be his most expensive soundtrack yet—he pulled themes from other movies as inspiration. Using the mood from another scene to evoke something new altogether.

His smile lit up the room. “I couldn’t have done this anywhere else besides America,” he enthused. “It’s amazing here because you get influenced by all these different kinds of music. All these different songs lead to different images and allow me to step into different worlds.”

Use What You Know, Expand from There

For the kid who spent much of his childhood cooped up in a tiny apartment, the chance to explore different worlds as a filmmaker was a dream come true. Scorsese used his own experience as an outsider to explore themes he saw in the world around him: the overwhelming need for acceptance; the conflicts inherent in love and desire; the driving hunger to ‘be someone’; the corruption caused by money and power. The conundrum of faith and doubt. Catholic guilt.

In a review of Scorsese’s second film, Boxcar Bertha (1972), Roger Ebert declared: “We get the feeling we're inhabiting the dark night of a soul.” That still holds true today.

Scorsese summed it up himself. “You start to question everything,” he explained. “I was raised as a Catholic, but— The faith that was instilled in me as a kid, that changes. Ultimately, it has been a long struggle towards a mature faith, whatever that is.”

With each film that he made, Scorsese continued to plumb the complex tapestry of human interactions, emotions—and then expanded his reach. At first, he stuck to crime, to life in the streets: a mix of mood and violence, both internal and external. Then came Raging Bull.

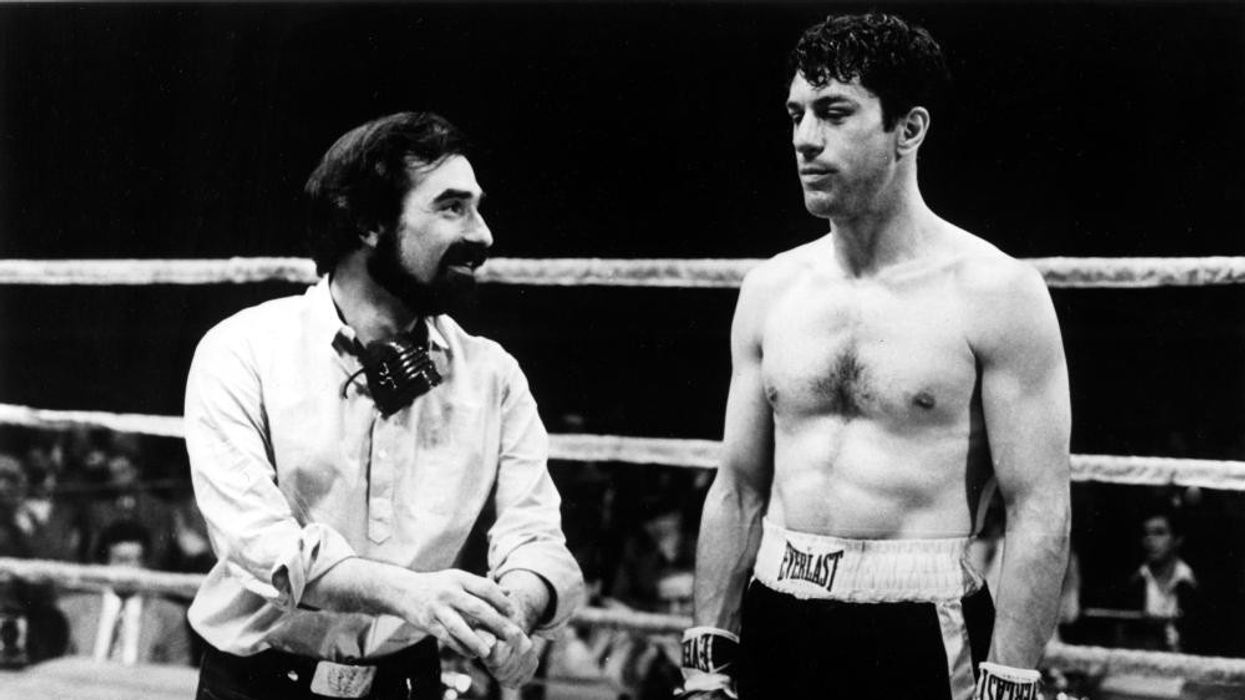

“I had been resisting it for awhile, a few years actually, because I didn’t understand boxing,” Scorsese recalled. But then he realized: Jake La Motta’s story explored the same human dilemmas that had haunted his earlier films. So he asked De Niro to help him understand the sport.

De Niro nodded, remembering. “You told me to go practice boxing, so you could watch and take videos of it.” As their training sessions increased, Scorsese began to develop the film in his mind. “I sat there in this gym on 14th Street and I suddenly realized, it’s overwhelming. We can’t just shoot this, I have to design it all.” The film had nine boxing scenes; based on De Niro’s choreography, Scorsese sketched his approach, frame by frame. “I wanted it to be like ‘The Wild Bunch,’ like Peckinpah, in terms of the choreography of the camera and the physicality of the boxing.”

By the time they started shooting, the pair had turned an unfamiliar world into a universal experience.

Play Against Type

By 1982, Scorsese and De Niro were both household names. They’d just won multiple Oscars for Raging Bull (1980); De Niro was being honored for other award-winners, including The Godfather Part II (1974) and The Deer Hunter (1978). But they were starting to feel cornered. Type-cast. Scorsese was best known as a “gangster storyteller”; De Niro was known for his macho wiseguys. They both wanted a challenge—and Scorsese suggested a film that would subvert expectations.

The film was The King of Comedy (1982), a sometimes underrated classic where De Niro plays Rupert Pupkin, a profoundly lonely comedian who lacks both audience and self-awareness. The result was a dark and disquieting portrait: a masterful distillation of ideas into one core character.

For Scorsese and his camera, it was also a new approach to storytelling. “I wanted to create a reset button in my head, so we shot it as simply as possible.” Eager to explain, the director uncrossed his legs, gazing out at the crowd. “I wanted to pull back and redefine what the narrative through the camera is. What it could be. Unlike my earlier films, The King of Comedy is very reliant on dialogue, and the relationship in the frame between people.”

To drive his point home, he called up a film clip: De Niro sitting in Jerry Lewis’s waiting room, staring up at the cork ceiling—so intently that Jerry’s gate-keeper can’t help but look up too. It’s a hilarious, character-driven use of composition that didn’t even require a camera move. As the clip played out onscreen, Scorsese laughed along with the crowd.

Once again, he made the unfamiliar familiar.

Choose Characters Who Move You

No matter how different the setting, Scorsese keeps returning to characters who move him, conflicted souls who fill the world as we know it. Like Raging Bull, like The King of Comedy, The Wolf of Wall Street gave us a struggling everyman, a microcosm who reflected a troubling macrocosm: in this case, a world of nickel-and-diming, of people taking advantage of each other while avoiding self-doubt.

In many ways, each one of his films is some form of moral interrogation.

Scorsese searched for the right words. “Ultimately, these films are about my own personal struggle: a struggle toward the very essence of faith. And uncertainty,” he ruminated.

De Niro brought up Scorsese’s 2016 film, Silence, as a good example. Scorsese nodded. “That film took me a long time to put together. It was based on a novel by [Shusaku] Endo, I didn’t know how to write it at first, but finally I think I got it.” A three-hour period piece, Silence was a 17th-century missionary tale set in Japan that tackled questions of faith, doubt and suffering. “The Irishman comes out of that too.”

Scorsese and De Niro grinned at each other: clearly partners in crime. The Irishman—scheduled for release in the fall of 2019—is their latest collaboration, cross-fertilized by all their past work, a natural vehicle for what they now own as a “mature” voice.

Fans beware: yes, this film will return the fabled pair to their comfort zone of violent crime—but according to them, it won’t be a remake of Goodfellas or Casino. Instead, it will explore the life story of wiseguy hitman Frank “The Irishman” Sheeran, adapted from Charles Brandt’s 2003 book, I Heard You Paint Houses—with a huge dose of emotional heft.

“Bob and I read this book, and it was profound. You really felt the heart of this character, these situations.” The director looked out at his audience, trying to telegraph his enthusiasm. “The Irishman isn’t necessarily about the trappings around the characters. It’s about the essence of who they are.”

The film will also break ground in terms of CGI. In order to allow Scorsese’s favorite actors to play younger versions of themselves, he is using cutting-edge ‘anti-aging technology’ to morph scenes from earlier films (ie, 36-year-old De Niro in Raging Bull). If it works as he describes, this will be a landmark moment for cinema: at long last, the eternal medium.

But that’s just an aside. Much as the new tech excites Scorsese, its ultimate purpose is to serve the same goal he has always had: to explore human nature, to pose difficult questions, to keep searching for answers.

One of the answers came early on, from his old parish priest, Father Principe. “He told us, ‘Get out of here. There are good people here, but you don’t have to live their lives—getting married at 21, having children, feeling trapped. Take the opportunity, take the advantage of where you are in this life.'”

For Scorsese, that was life-changing advice: not only did he "get out," but he has spent his career exploring the lives of other outsiders, characters caught in a lifestyle that builds them up, then destroys them—unless they’re wise enough to get out. His eyes sparkled behind his oversized glasses, a lifetime of cinema playing in his mind’s eye. “The years have gone by and I see differently now. I think and I hope from a different vantage point.”

Again, De Niro gave a slow nod.