Turning 1000 Hours of Footage into a Devastating Family Doc

Davy Rothbart's "17 Blocks" is a family's two decades, distilled into a heart-wrenching 90 minutes.

When Cheryl Durant was young, she dreamed of being a movie star. "Unfortunately, life had other plans for me," she says in Davy Rothbart's documentary, 17 Blocks. Neighborhood violence claimed her husband's life; drugs overtook hers. She struggled to support three kids as a single mom in the urban blight of Washington, D.C.—just seventeen blocks from Capitol Hill but effectively worlds away.

The story with Rothbart's movie is much the same. When Rothbart starting filming 17 Blocks, he thought he was simply documenting his time with the Durants. He met nine-year-old Emmanuel and teenagers Smurf and Denice in 1999 on a local basketball court; when they became closer, Emmanuel expressed interest in the camera, and Rothbart started lending it to him. Other times, he'd film the family himself, as they hung around the house and enjoyed each other's company. But Rothbart could never have predicted what kind of film he was actually making.

Over the course of 20 years, the camera watches the kids grow up. We grow to love them. We root for Smurf to transcend the siren song of drug dealing. We watch Denice become a young, capable mother. We watch Emmanuel overcome the odds and achieve academically, setting himself up for a promising career. Although things are tough in the under-served neighborhood, the Durants get by. Their seemingly endless reserve of love and support for each other seems to safeguard against the dangers and challenges they face.

Then, there's an earth-shattering tragedy, and nothing is ever the same again for the Durants.

To say more would be a disservice to Rothbart's film, which hits you like a ton of bricks in its third act. The family's suffering feels immediate and even personal. 17 Blocks is empathic filmmaking at its best. No Film School sat down with the director to discuss why he kept himself out of the story, despite the fact that he was very much in it; how he distilled 1,000 hours into 90 minutes; and more.

No Film School: Your movie destroyed me.

Davy Rothbart: Well, I'm so grateful that you got a chance to see it and that you felt the ways that the family and I hoped that people would. The family's so excited to be able to actually share their story in a big way.

NFS: I want to know everything about how this came to be. I liked that you didn't overly emphasize the process of the film, even though it was incredible that you filmed over two decades. The film just kind of presents the story to you and foregrounds it in this family's experience.

Rothbart: Well, it was 1999, and I was a couple of years out of college. I moved to D.C., stayed on my friend's couch. He lived on the backside of Capitol Hill. A few blocks beyond that was a basketball court where I used to play almost every day. I met Smurf because he would always play at the same court. We just kind of hit it off. His little brother, Emmanuel, would always kind of be watching us through the fence, trying to play with the big guys in their 20's.

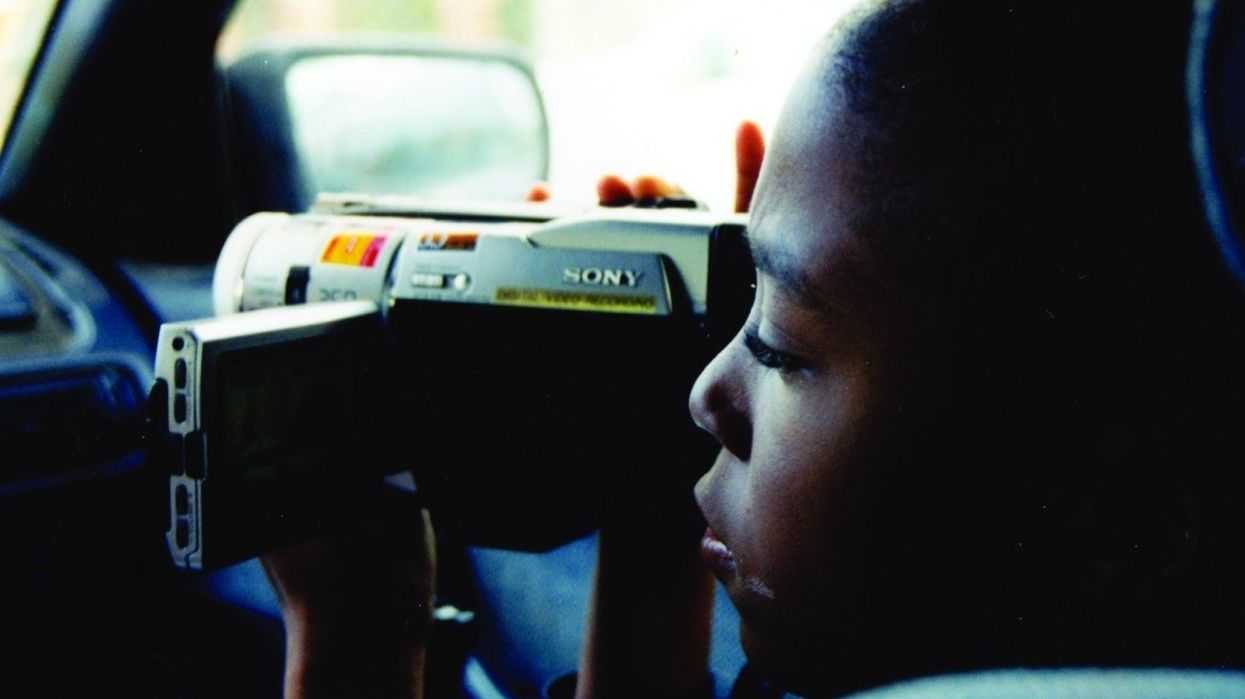

I think I had just gotten the video camera because I wanted to learn filmmaking. I was curious about it. Emmanuel saw it one time and he was interested in it. I just handed it to him, I showed him how to use it, and he started filming with it.

Eventually, I had an idea for a narrative film and I thought Emmanuel would be good to be the star of it. He was into the idea. I went to meet his mom to ask her permission and she was cool about it. But within a week of filming, I realized that my idea was stupid and wasn't going to be interesting. But I'd already gotten to know Emmanuel and his family and they were so cool and welcoming.

"Now it's time to find some way to piece together 20 years of footage into a 90-minute film."

Emmanuel was so interested in learning filmmaking. There was no real plan. We would just roam around the neighborhood. He would hold the camera and interview people on the street. Sometimes, at his house, he would interview his family, then his brother and sister until Smurf started filming. They would interview me. I would interview them. It was just a camera being passed around. I started leaving the camera with Emmanuel and his family at night and on weekends, sometimes a week or two at a time. I was just so taken with the footage that they were shooting. Emmanuel had a poetic eye for a nine-year-old. He was shooting some really lush and beautiful stuff—as much as you can with a $300 camera.

What really happened more than anything was—as Sheryl likes to put it—the family adopted me. I was a little lost and far from my own family. Having them in my life, and having a place to go every day and hang out... that meant a lot to me.

Over the years, I would come back, after I left D.C., to spend time with them. They felt like family to me. It was just a close friendship, but the camera was always a part of it. Whenever I would see them, we would film some more.

10 years later, I was so proud of Emmanuel. He was graduating high school, engaged to his high school girlfriend, training to be a firefighter. Against some pretty incredible odds, he had really prospered. We were all so thrilled. I did go back for a few weeks that summer to film because I thought we could piece together all the footage from his childhood, and stuff he'd shot and I'd shot over the years, along with this sort of triumphant ending. He was celebrating the fourth of July with his family. It was just a beautiful time.

Rothbart: A few months later, it was New Year's Eve. Emmanuel and I always talked on New Year's Eve. So I was expecting his call.

My phone rang. It was him. But it was actually Denice, and she was calling to tell me what happened. It was utterly shocking and devastating. I was on a plane the next morning to D.C. I asked, "How can I help?" Cheryl was just like, "Where's your camera?" I was like, "What do you mean?" It's unbelievable how perceptive she was, and how much wisdom she had about the situation. She just said, "So many kids are killed in this neighborhood all the time, but none have been documented their whole life like Emmanuel has. We need to tell his story."

Her friends had gone through losing sons and daughters through gun violence, and she had supported them through those days and weeks. She knew what was coming in the days, and weeks, and months following. She was like, "We need to film all of it, so people really get what it means to lose someone in this way." I just followed her lead.

"Emmanuel had a poetic eye. He was shooting some really lush and beautiful stuff—as much as you can with a $300 camera."

Together with everyone in the family, we tried to record all those big moments. Nobody should have to lose a family member in that way. Certainly, nobody should have to clean their brother's blood off the floor in their front hallway. Nobody should have to go to one of these T-shirt shops that specialize in memorial T-shirts. But being with them throughout those days, weeks, and months that followed gave me a better understanding of what it means to lose someone in that way.

But then we didn't even stop filming. Our friendship continued. It's been really amazing to watch Smurf and Denice's kids grow up, I think it was when they got to be 10 years old, like Emmanuel was when he first had a camera, that I sort of felt like the story had come full circle. Like, now it's time to find some way to piece together 20 years of footage into a 90-minute film.

Fortunately, we had Jen Tashara, this incredible editor, helped with that. She just won the Best Editing Award last night.

NFS: How many hours of footage do you have?

Rothbart: I think about a thousand, give or take. It's pretty crazy. [Cheryl, Emmanuel's mom] watched every minute of it, and the family collaborated deeply. We made this together. We talked with the family throughout about what story we wanted to tell with this footage. Which scenes are most important? The family really led the way in terms of what should be in the movie.

NFS: Can you talk a little more about the process of editing with the family, and with your editor? I can imagine it was not straightforward.

Rothbart: Yeah. I want to give a huge amount of credit to Jen. She's made a lot of great films already, and I've been friends with her almost as long as I've known the family, so she'd always known about this project. But I was so thrilled to get her on board because she's a great storyteller and she just fell in love with the family.

We watched all the footage and she started constructing a version of the story. We were still continuing to shoot at that point. For example, Cheryl said, "You know. We've talked so much about substance abuse and the way that's affected my life, and the chain reaction it's created for my kids. But I don't think you've ever actually filmed me using drugs. It's ugly. People need to see it. I'm about to use drugs. It's important to get it on camera." So we added things like that.

NFS: Were you working on 17 Blocks in between different projects? How did you make it all work?

Rothbart: Yeah. I worked on it a little for a very long time. In the last three to four years, it became more of one of the main things on my plate.

Over the last 20 years, I started a magazine, Found Magazine. I made three other films. I wrote a book called My Heart Is An Idiot. Soon after I met the family, I started working with This American Life in 2001 as a reporter. I've done 10 stories for them.

So, I was always busy doing other stuff. This was just something that I would work on in fits and starts. Sometimes I would go [to D.C.] for a couple of weeks, hang out with family, and work on it. There was always more to capture.

"Each time you pull out a scene, you knew it was the right decision, even though you were sad to lose this scene that was special in its own right."

Now, it's surreal to think that it's done. Having Smurf's son here at the festival this past week was really special. I think they both have a little bit of a filmmaking itch, and so I'm going to get them some cameras this year and encourage them to start filming their lives, too.

NFS: Looking back on the whole process, what were some of the most challenging elements that you encountered along the way?

Rothbart: Jen has found a lot of moments in the footage where you can overhear [the family] asking me while I'm filming, "So when all of it going to be done?" or "What's happening with the movie?" And I always said—and I meant it, at the time—"I think, like, in three to six months, we'll edit something together." You hear me say that in 2004, 2007, 2012. I think at some point, they never thought there would be a finished film. It was just like, "This is Davy's weird hobby."

Now, the storytelling works, but there were so many other great scenes that are incredible that we wanted to have in the movie. One challenge is just, how do you pare it down? I would love to have a three-hour version of the movie. Losing scenes I loved was hard. Each time you pull out a scene, you knew it was the right decision, even though you were sad to lose this scene that was special in its own right.

I think, honestly, just losing a brother and a friend was most the most challenging. And recognizing that he's one of hundreds of thousands of kids whose story this is.

At the end of the movie, when I see all of those names [of gun-shot victims], each time I watch the movie, I notice a different name. I just imagine, "Well, there could be a whole documentary made about that kid's life, too." That's challenging to me—recognizing the scope of the problem.