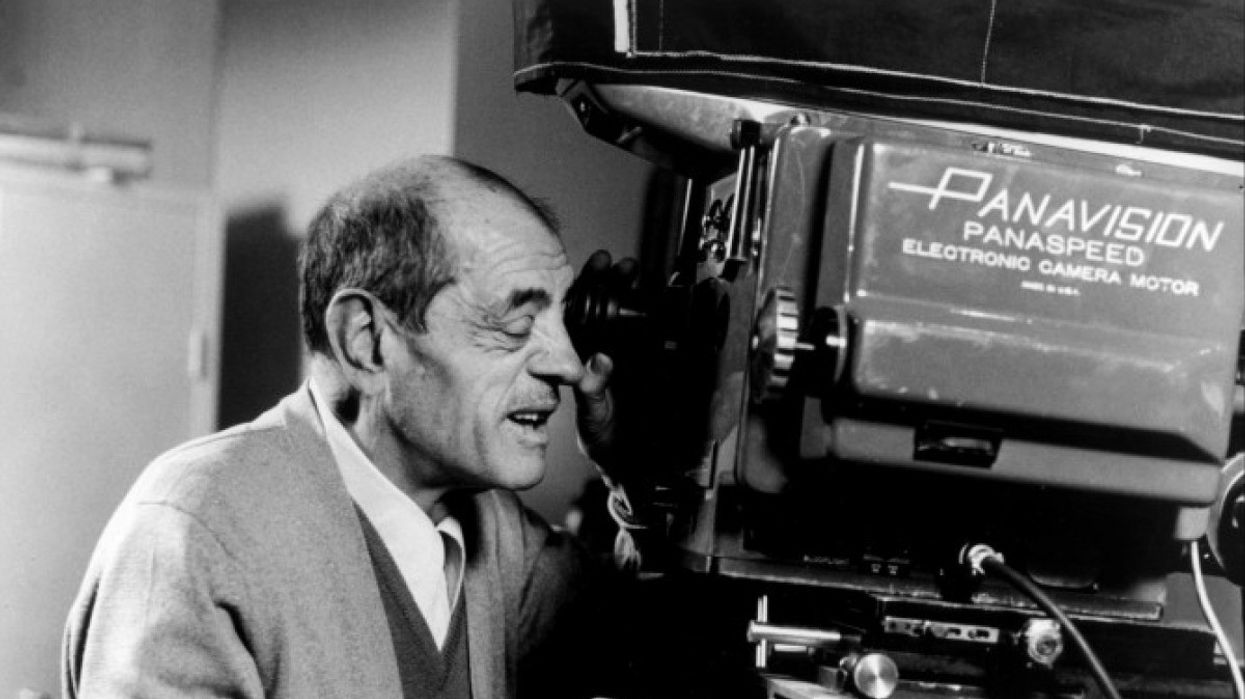

Happy (Belated) 114th Birthday to Luis Buñuel, Father of Surrealist Cinema

Luis Buñuel was a creature of the 20th century. Born in 1900, he died in 1983, and February 22nd would have been his 114th birthday. It is almost impossible to overestimate his influence on cinematic surrealism, though ironically, his biggest contribution to the movement was made without its official "blessing." No matter, along with a group of artists which included famed visual artist Salvador Dalí, his contributions to motion picture surrealism are still shocking young filmmakers today, and his works, along with his later cohorts, friends, and enemies, are required viewing for anyone who wants to understand how cinema became more than a record of life, but a rendering of the dream. On the occasion of his birth, we look back at the Spanish-Mexican filmmaker's life and work, including his best known film, the silent 1929 short Un Chien Andalou.

Rise of Surrealism

Surrealism rose out of Dada, an artistic movement which believed, in part, that an excess of cold rationality brought about the carnage of The Great War, later known as World War I. This conflagration destroyed a generation of Europe and threw the old world into the new in a blood-drenched tide. The stated aim of Surrealism was to undermine the scientific, rational precision which was taking over every facet of life, using the Freudian conceptions of the mind and specifically the unconscious to, "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality."

Up until this point, in the early 20th century, the common view was that civilization was on an unstoppable onward and upward curve towards perfection, perfection aided by science. The Surrealists, led by André Breton, rejected traditional meaning in favor of an art dominated by the unconscious, the new and little understood part of consciousness which operated underneath daily consciousness, working via symbols and apparent randomness.

Breton defined surrealism as: "Pure psychic automatism through which it is intended to express, either orally or in writing, or in any other way, the actual way thought works." And Un Chien Andalou, which means An Andalusian Dog, the name of a breed of dog from the Andalusian region of Spain, certainly follows a dream logic. Decades later, the film would also inspire "Debaser," a very rad song by The Pixies.

Un Chien Andalou

Of their famous first film, Buñuel later recalled: "Our [Dali and Buñuel] one and only rule was very simple: no idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted. We had to open all doors to the irrational and keep only those images that surprised us, without trying to explain why." As filmmaking is a labor intensive, industrial process, this was, to say the least, a risky proposition. Interestingly, the film was a huge hit with the French bourgeoisie, playing for eight months in Paris and making stars out of the two. Naturally, this led to Buñuel's disgust:

What can I do about the people who adore all that is new, even when it goes against their deepest convictions, or about the insincere, corrupt press, and the inane herd that saw beauty or poetry in something which was basically no more than a desperate impassioned call for murder?

The images are startling and manage to haunt long after the few 'scenes' of the film are done, and this is a low-budget, silent, short film more than 3/4 of a century old (so there's no excuse for you not to get out there and put your vision on the screen!). In fact, one could argue that Un Chien is the first low-budget indie film, since by 1928/9 there was most definitely a production and distribution system in place, and Buñuel and Dalí were working completely outside of said system, self-financed, and so low-budget that Buñuel had to edit the film in his kitchen without the benefit of any equipment save his (unsliced) eyeball and, ironically enough, razor blades and tape. It has also been argued that the film was an inspiration for the symbolic, associative editing and imagery in music videos -- many commercial directors saw the film in school, which for years was one of the few places that had a print to screen.

I first saw the film when I was 17, with a live piano score, and this version, one of the many on YouTube (be warned, though: there are many versions online, featuring many different and cool soundtracks, though they have also been struck from film prints ranging in quality from the pristine to the nearly unwatchable) comes from the original negative and was struck in 2003 from the highly flammable nitrate film stock on which almost all of cinema's early classics were shot. Nitrate stock, as can be seen below, is highly volatile, and will catch fire if you sneeze around it, and so unless transferred to safety stock or digital, runs the risk of literally burning up huge swaths of cinema history:

Kuleshov Effect

The movie, while not the first, was certainly one of the most influential surreal films, and led to Dalí and Buñuel being officially invited to join the Surrealists one evening. There was plenty of surreal art and literature by this point, but film grammar, in both the US and USSR, had been mainly concerned for decades with establishing itself as a coherent dialectic montage, whereby, e.g.,the Kuleshov Effect, a Soviet innovation, established that the neutral face of an actor was be interpreted as any number of emotions, contingent on what the next shot in the sequence was. This foundation of editing is part of the basic grammar used today in everything from commercials to blockbusters and helps create the illusion of temporal continuity, a building block of narrative, even if it isn't used in the strict dialectic, Soviet Marxist sense in which it was invented. But it is a building block of the POV shot, reaction shot, insert, etc.

Surrealism concerned itself with dismantling this structure of mimicry of consciousness. Dali's visual genius and Buñuel's raw filmmaking skills created Un Chien Andalou, shot in 1928 and released in '29, and financed by Buñuel's mother, and was the best example to date of what could be accomplished when film was treated as more than a frame on which to hang a linear story (Buñuel began as a film critic, later worked as an AD, but aside from a short stint at a private film school, was untrained in the technical aspects of filmmaking).

L'Age d'Or & Later Careers

Success led to another collaboration between the two, the feature-length L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age), but it also led to a nasty falling out, with accusations hurled back and forth along with further proof that 'good fortune' can be its own downfall. Dalí was essentially a Royalist who supported Spanish dictator Franco, while Buñuel's leftist politics led him to press on and shoot the film on his own, and mostly in sequence, owing to his relative lack of filmmaking experience. Its presumed anti-Catholic sentiments led all prints to be withdrawn and not seen in public again until 1979, since when the Vatican threatens to excommunicate the financiers, they tend to get skittish:

The success and infamy led Buñuel to Hollywood, where he worked for a short spell under studio boss Irving Thalberg. Meanwhile, Dali went on to a successful career in painting. Buñuel, in later years, would have a successful and respected career as a filmmaker, producing many classic art films such as The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

The interested viewer is encouraged to check out the many resources available online which provide the free education that used to be available only to film students. Directors to check out include Man Ray, Jean Coucteau, Reneé Clair and many others.

Other Surrealist Filmmakers & Those Influenced By the Movement

Despite the creator's insistence on his work's misapprehension, it's almost impossible to state the impact Un Chien Andalou had upon its release, particularly on other filmmakers. The first entry in Jean Cocteau's trilogy, Le Song D'un Poete (The Poet's Song, 1930) owes much to the film:

Probably the biggest and most mainstream American director who was influenced by the Surrealist movement is David Lynch, and this is particularly evident in his early shorts (This video is part of a playlist featuring 70 surrealist shorts, many of them by Lynch):

Many other Surrealist films can also be found at this post by Fandor, which you should definitely check out.

What do you think? Are you a Surrealist, or a confirmed narrative nut? Do you find the juxtaposition of 'random' images fascinating or maddening? What do you think an indie filmmaker can learn, both from the aesthetics and the working methods of these filmmakers? Let us know in the comments, and feel free to post a .gif of a trout if you think that would prove your point better than words!

Link: Spotlight on Surrealism -- Fandor

(This post has been a short survey of the genre, focused on Buñuel's birthday, and is in no way intended to be a canonical list or survey of the genre. This is merely an introduction with a couple of examples for the curiouser and curiouser.)