How 'Gleason' Director Turned 1,300 Hours of Footage into the Moving Story of an NFL Player

Ex-NFL player Steve Gleason sets out to capture his spirit on film for his unborn son.

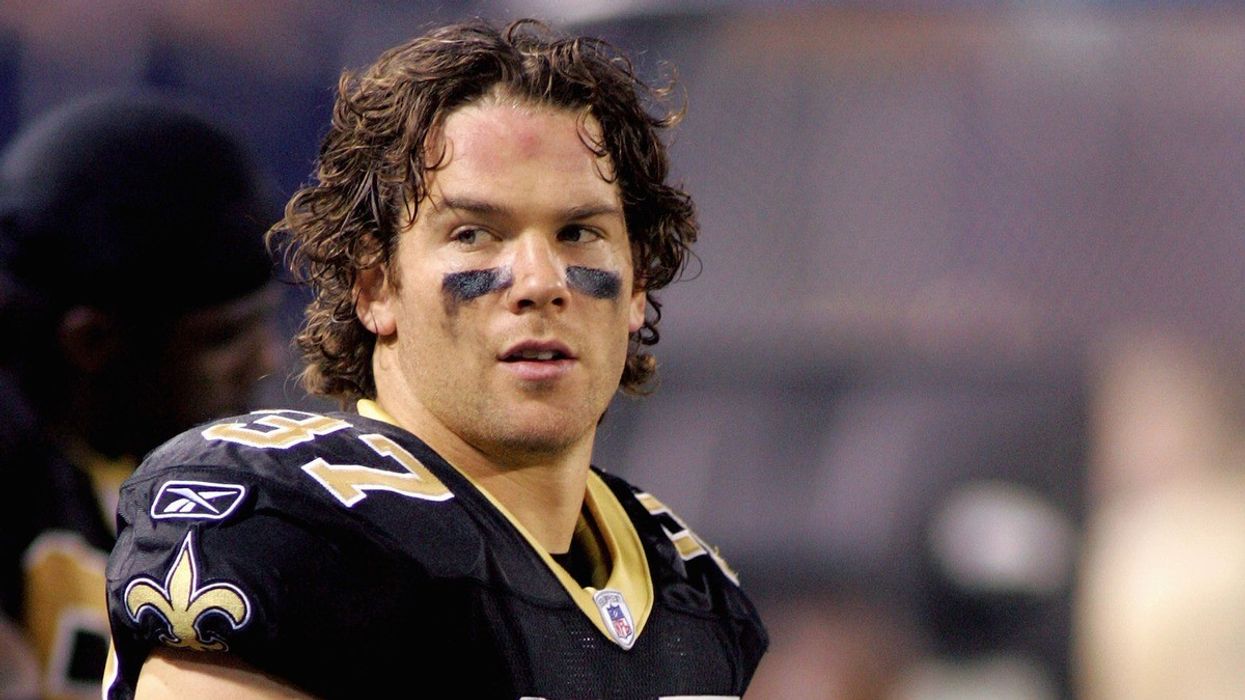

NFL star Steve Gleason made the play of his life in 2006 when he blocked a punt and led his team to victory, establishing New Orleans as a city that never gives up. A few years later, he was diagnosed with ALS (also known as Lou Gehrig's disease), a rare condition that quickly deteriorates the muscles until, ultimately, the lungs fail.

Gleason is the former football player's attempt to document himself so that his son can get to know him. Thousands of hours of footage later, director Clay Tweel pieced together the progression of Gleason's battle with the affliction.

No Film School spoke with Tweel at SXSW 2016 about finding the story, editing down 1,300 hours of footage, and reinforcing his beliefs in universal truth.

"I had to shut myself off while we were editing because it was too overwhelming. I didn't really get emotional about the story or any of the footage."

NFS: How did this project fall onto your plate?

Tweel: I came out to LA to be a production designer about 12 years ago. I'd worked on a movie called Cry Wolf with Seth Gordon, who was the editor. When I moved out to LA he gave me Final Cut Pro and After Effects and he was like "Learn these and I'll get you some work." He really kind of took me under his wing. I started working on The King of Kong and that was a 3-year job that was my film school. I learned how to do editing and motion graphics, and I made a song that was in the movie. They were stupid enough to allow me to learn on the job and do lots of stuff. That's where I fostered my love of documentaries and got a strong editorial background. Then I started directing, and Seth and I worked together on a lot of other docs.

Fast forward to Sundance 2 years ago. I was sent a teaser trailer for this project. It was about 5 or 6 minutes long, and it just floored me. I was so blown away by how powerful even just this short snippet was. Steve and [Michel Varisco Gleason, Steve's wife] had been filming themselves, and then these two young filmmakers, Ty Minton-Small and David Lee, came on and started helping the family film. They became so ingrained in the story that they started care-taking for Steve and living with the family. They became like brothers to Steve and Michel and they amassed a ton of footage over 3 years.

NFS: Too much footage?

Tweel: Yeah, too much, and they were admittedly too close to the story to try and figure it out, so they cut a teaser trailer in order to go try to find a director.

NFS: I was watching it on a screener and I literally had to pause the movie and text some people and tell them that I love them. Or just apologize for something. It made me think so much about the impermanence of everything and the will to not give up.

Tweel: Those are my favorite pieces of feedback. I've gotten that a handful of times, people saying, "I left the screening and I called my mom and we had the best conversation we've had in like 10 years." The fact that the movie seems to be having a real impact and changing people's perspectives and lives along with bringing awareness to ALS... that's more than you can ask for as a storyteller.

"Just understand that your original intention is 100% not going to be what the movie is."

NFS: How did you secure the job after you saw that teaser?

Tweel: It blew me away and I jumped on a plane a couple days later and flew to New Orleans to meet up with Steve and Michel. There's a real energy around them that just draws people in. People love to be around them and they are fun-loving, powerful individuals. I got to talk to Ty and David and some of the other producers that were down there, and then I was kind of pitching myself and how important this story was. I guess a side note is that my dad is Muhammad Ali's lawyer and I grew up with the Alis — both Muhammad and his wife Lonnie, who is one of the smartest, coolest people I have ever met. Michel and Lonnie are my heroes. I have always wanted to try to find a way to tell their story, but every piece of archive on Muhammad has been used like 50 million times. Steve and Michel's story was an interesting parallel that I thought I could explore, and I talked to them about how much I thought the story could be appealing to a large audience. I found out later I was the only person that flew to New Orleans, and I think that's what did it.

NFS: There's some really interesting stuff about being a hero and how he was able to do that — no matter what.

Tweel: I talked to Scott Fujita, who's a producer but who also was a football player, and he talked a little bit about that in addition to what Steve says in the film. It's hard to be on a football field with 90,000 people screaming for you, and just have to have that go away. That's a hard psychological hurdle to overcome for anybody. Then, on top of that, having to deal with all of a sudden getting a terminal diagnosis. There are a lot of things that Steve is having to confront in himself. Both he and Michel are so vulnerable and open and honest and articulate about how they are going through these things. That's what makes it, I think, so powerful.

NFS: Yeah, it's an example for every person of how to overcome adversity. That footage of him walking the football field... My god....

Tweel: I kind of had to shut myself off while we were editing because it was too overwhelming. I didn't really get emotional about the story or any of the footage I was watching for most of editing. After I saw that teaser trailer and I cried, I kind of put my director hat on and was just like, "Okay, we've got to find a way to get this done." I'm more into the nitty gritty nuts and bolts.

But that scene when he goes on the football field to lead the "Who dat?" chant.... It was about 5 days before our Sundance premiere. We're in the sound mix, we had just laid in the new track by our composer Dan Romer and Saul, and I was watching it against picture for the first time, and it hit me. In a dark theater watching it, it just kind of all came rushing back. It's a tricky balance. How do you feel what these people are going through, but also from an anthropological point of view, and then allow the audience to be connecting with and relating to them in a way that you're not while you're making it?

"Our process is not very different from a writer's process on a fictional narrative movie."

NFS: Years of editing will only prepare you for so much.

Tweel: We had 1,300 hours of footage when Ty and David stopped filming and we decided to start editing. I had to go back and Seth and I went and shot a couple of sit-down interviews to tie the room together and add a little context. Over the years, I have developed a system for how to organize and structure our footage. It was a system that Seth developed on The King of Kong that I learned, and then over the course of many movies have adapted to my own way of thinking. It was a pretty Herculean task to take that many hours, and we had a couple editors come on. All day every day you're watching footage for like 3 and a half months, trying to put things in their proper place.

NFS: The film is paced very well and you really feel the progression of his physical decline.

Tweel: That was something that was important to everyone, including Steve. He wanted to show the kind of daily challenges of ALS, but he wanted to really make sure that people understood what the progression was like. We were pretty stringent about our timeline in the movie — when things are happening and at what point Steve is in his progression of losing motor skills, or losing speech, or the different procedures that he undergoes. That was yet another kind of box that we were putting ourselves in that we had to deal with structurally when putting the story together. So on top of trying to arch out a film and a kind of journey for a character, you have to have it be in chronological order too.

NFS: Did you shoot additional footage?

Tweel: Our process is not very different from a writer's process on a fictional narrative movie. We have a cork board, we have index cards, color-coded via character and or theme, and we are trying to plot out an outline of what we think the movie's going to be. We looked through all the footage and figured out where some holes were. Of all the 1,300 hours that were shot, no one ever asked [Steve or Michel], "What's going on, and how do you feel about it?" We needed to go in and have a little bit of context dropped in. We shot a half dozen sit-down interviews and shot some things that happened over the course of 2015 with the family.

"We're trying to avoid empathy exhaustion. You don't want to get to the point where you're halfway through the movie and you're all cried out."

NFS: What was the biggest obstacle in making this?

Tweel: It's twofold. Finding a story in all those hours, really distilling it: What is that core principal that everything has to relate to? Coming up with what that filtration system is that's going to help you narrow down into a palatable two-hour movie. That was probably the biggest challenge. Second, I think having a movie that has a balance of the lightness and the darkness, the tragedy and the comedy of everything. Michel and Steve, they're legitimately hilarious people. They're fun to be around, they're charismatic. We didn't want to have that get lost in the more tragic or poignant parts of the story. A term that I think Seth coined was we're trying to avoid empathy exhaustion. You don't want to get to the point where you're like halfway through the movie and you're all cried out.

NFS: Any advice for other filmmakers?

Tweel: From the get-go, be okay that [your movie] is going to change. Just understand that your original intention is 100% not going to be what the movie is. Accept that, and sketch something out and know that you're going to be re-sequencing; you're going to come up with an entirely new sub-plot. For example, on this movie, I did not know the depths to which that we could explore Michel's character and all the struggles that she was going through, which proved to be super powerful.

NFS: What was your technical workflow for this film, since you shot over many years across different formats?

Tweel: I'm the lead editor as well, so I'll throw you a technical bone. It was every kind of format that you could imagine: everything from a C00 to a DSLR to a handy cam, to three different flavors of iPhone codec to GoPros, everything. We started editing last March and it was a very intense time table: the goal was get the movie into Sundance. To watch all that footage and to put together a cut in 7 months was insane.

Because of that, we did the math and figured out that if we tried to transcode all of that footage in order to use Final Cut or perhaps even Avid, we would have lost about 4 weeks. We used Premiere for the first time in my life — I've been on Final Cut for a decade and since [Apple] kind of stopped making pro software and Final Cut 7 is going the way of the dodo, I just jumped foot first into Premiere and had to figure a lot out. There's a lot of growing pains, but in the end I think we saved a good chunk of time on a tight post schedule.

"This movie just reinforced for me that if you mine somebody's story correctly, there's going to be a deeper truth that's embedded there that we can all enjoy and connect to."

NFS: Let me guess, you had trouble exporting?

Tweel: [Laughs] Yes. I got all sorts of work-arounds for exporting. We can do a whole other article on post workflow.

NFS: How do you navigate and get the most out of your film festival experiences?

Tweel: I don't do a ton of parties, but I like to do meet-up type events where you're going to be talking to other filmmakers. I like the talking shop. Talking with other documentary editors, directors and being like "So, what did you shoot on?" "What were the snags that you came across?" Talking about other people's experiences with distributors or theaters. Those are valuable things. There's a happy hour that they do here [at SXSW]. Go to those and just meet other filmmakers.

NFS: What was the biggest thing you learned making this film? Anything you will do massively different next time?

Tweel: My passion for telling stories in the documentary format is trying to get to the core of the motivations of why people do what they do. It sounds super cliché, like: "Oh, everyone has a story." But I think that there really is a universal truth that people can relate to. This movie just reinforced for me that if you mine somebody's story correctly, there's going to be a deeper truth that's embedded there that we can all kind of enjoy and connect to.

I love subverting expectations. All the movies that I've done — a movie about teenage magicians, or a movie about 3D printing entrepreneurs or two rednecks fighting over a leg in North Carolina. Once you get past the premise of the first ten or 15 minutes, the movie becomes something completely different. I hope that people understand that this movie has very little to do with football and, in some ways, ALS. It's a story about humanity. It's about a father and son, an inter-generational relationship. It's about living life with a purpose. Those are pretty grand themes.

For more, see our complete coverage of the 2016 SXSW Film Festival. Listen to our podcasts from SXSW (or subscribe in iTunes):

No Film School's coverage of the 2016 SXSW Film Festival is sponsored by SongFreedom.