Meet the People Who Capture Entire Lives in 800 Words: Vanessa Gould on 'Obit'

Documentaries about the media industry are familiar territory, but you’ve never seen one like Obit before.

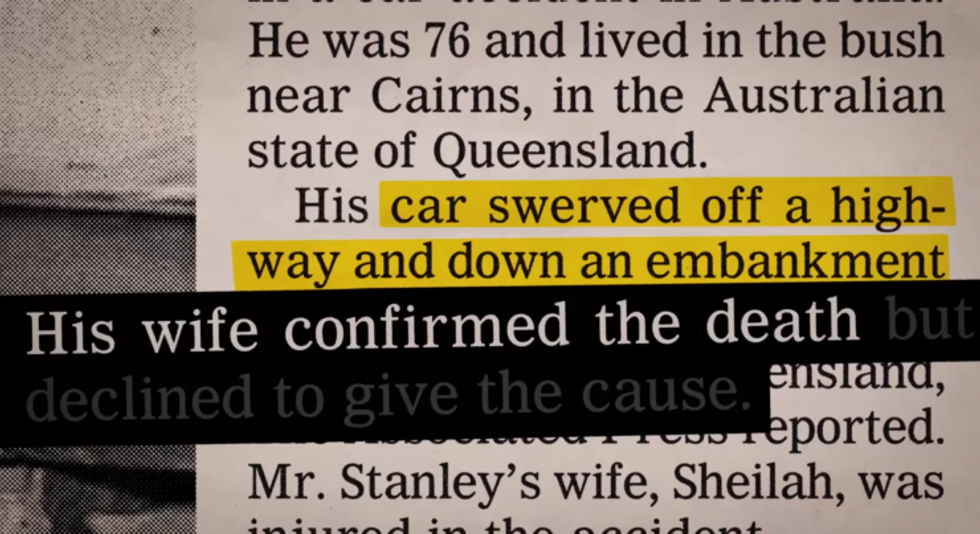

A profile of the Obituaries section at the New York Times, Vanessa Gould’s film follows the reporting team as they work on tight deadlines to research the deaths of influential figures. Along the way, they muse about getting one shot to capture the essence of a life while pondering their own mortality and place in the world. The film edits archival footage of the obituary subjects in a poetic fashion, often narrated by words from the obituaries themselves, to create a moving portrait of reckoning with life and death.

Ahead of Obit’s April 17 world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, No Film School spoke with Gould about the similarities between documentaries and obituaries, the film’s “pointillist” philosophy and bugging the New York Times newsroom.

NFS: The writers talk about their work not being about death at all, but about celebrating the lives of their subjects. Was that your original perception of this film, or did talking to them change your perspective?

Gould: I wasn’t sure beforehand, but I think it’s a common phenomenon that things aren’t what they seem. And when that happens in documentaries it’s a really satisfying approach. Once we started realizing that the film would be about life instead of death, it was a natural inclination to start working under that framework. But when my friend died, after my last film (Between the Folds), and I was helping one of the writers write his obit, she didn’t ask any questions about how he died. We were very focused him and his achievements, and what he was like as a person, and what he loved, what meant a lot to him. Even on a subconscious level I probably sensed that–maybe I didn’t realize that it was “about life,” but I certainly knew it wasn’t “about death.”

The way that this project came about was that one of the subjects in my last film who was closest to me was a very reclusive French sculptor who lived in Paris. Being a poor Parisian, all he did was smoke, and he got lung cancer and died at the age of 54, in the middle of this hype–he had just begun to really thrive creatively, and what he was doing with his work was mind-blowingly gorgeous and unique. And to lose somebody at the height, the pinnacle, of their artistic progress was just as devastating to me as the loss of a friend. I felt this desire to have him be recognized and have his work be recognized and entered into the public record somehow. Otherwise, naturally, things just disappear.

So I called all the major newspapers, really, in the world, and sent them a couple lines about who this artist was and asked them to contact me for more information. And nobody did for a couple days, and I was getting so despondent. And then, out of the blue, about a week after, none other than the New York Times called me, and they assigned one of their best writers to it, and they ran a beautiful obituary on him with a slideshow of his work. And I just had this moment, like, “Why on earth would the New York Times run an obituary about an utterly unknown, hermetic French artist?” And that just got me thinking about what culture is and what journalism is, and that’s when I got the idea to do this film.

NFS: How did you know that profiling them would make for such an interesting movie?

Gould: Well, I didn’t. [laughs] I made films before this and as I was beginning to get acquainted with reading obits, I really did see the relationship between what a documentary is and what an obituary is–this hyper-reductive, distilled essence of something, whether it’s a life or a story told on film. But you’re really taking in the whole picture and then figuring out how to do insane economy to express the salient elements.

So I felt this kindred spirit, a little bit, with what these people were doing, albeit in a different medium. But I started to really like the fact that in the newspaper every day, where you see this minutiae about legal cases and football scores, the daily beat of whatever goes on in the newspaper, that in the obituary corner are these full stories that are crafted so beautifully. And sometimes you could look at every single one of those lives and be like, “Oh, my God, that’s a documentary waiting to happen.” So I had a fair amount of faith that, even if I was going to take this meta-view of the desk as a whole and the people who were writing these things, that it would have a chance of working in a film. But we never really knew until we got into the edit.

"Once we had all our bags and gear boxes out of the way, we just sort of shadowed them as they went throughout their day, and I think for the most part they sort of forgot about us."

NFS: How did you approach the Times with the idea for this story, and what was that process like of getting to film inside the newsroom?

Gould: It was tough. They had done two other films previously, Bill Cunningham New York and Page One. So they were appropriately guarded and cautious when I first approached them. But I was pretty determined and I believed in it. So I had a series of meetings with their editor, and he played a fair amount of devil’s advocate and really tried to get to the heart of what I was trying to do. And I think they had been asked by a number of other documentary filmmakers to do portraits of them in the past, and they’d said no. But somehow, through the course of several meetings, he said, “OK, let’s meet with the entire staff,” so I met with all the editors and writers and sort of gave them a full pitch. And after that pretty much everyone signed on.

I had to meet with their corporate communications people a few times, and similarly they were appropriately cautious. We just had to lay down some really clear rules about confidentiality, because there’s a fair amount of sensitive information being tossed around the obits desk. They just wanted to know that they, as an institution, could trust me as an outside individual, so it was a fair amount of planning.

And we filmed the [reporters’] interviews in their houses, because I really wanted to bring them out as characters. We only shot in the newsroom for maybe five or six days total. And it was great. We would load in before any of the writers got to work. We used the leanest crew possible, for reasons that are obvious. We shot on two RED cameras and had a field sound mixer. Once we had all our bags and gear boxes out of the way, we just sort of shadowed them as they went throughout their day, and I think for the most part they sort of forgot about us.

Gould: It was mostly the latter, but as I was proposing the film to them, I said, “Your executive committee can see the film before the public does.” And I think that assurance just being offered and set in place allowed them to know that nothing was going to sneak out. But then we also signed a number of confidentiality agreements assuring them that, for example, no one who was considered for an obituary but didn’t get one could ever be revealed on camera, for reasons that are obvious if you think about it. So we bugged the newsroom and had a couple ambient mics going, and we had to go through all that stuff just to make sure that nothing [bad] was picked up, and that anything that did make it in was publicly vettable, through either the fact that they did run the obit, or other things. With those two agreements in place, I think they felt confident.

It was essential to get them to have complete peace of mind and not have to worry about what they were doing, for them to obviously appear natural on camera.

NFS: That’s interesting that there were things you couldn’t reveal on camera, but then they were open about, for example, the advance obituaries for people who haven’t died yet.

Gould: Yeah, and that’s actually something–I don’t know how many people are going to pick up on that, but when I was interviewing [the reporter] Bruce Weber and he said, “We’ve got a lot of people,” he names Stephen Sondheim, [Harlem Globetrotter] Meadowlark Lemon and whatnot, I said, “Top secret,” thinking that he wasn’t going to budge. And he said, “No, I’ll tell you who.” It was a total breach of protocol for him to do that, on camera no less. So we loved it, and we put it in the film with huge asterisks next to it, expecting that when we showed the corporate people, that they were going to wring their hands and be like, “Stop.” And I have no idea why, but they looked at each other, they thought about it a little bit, and then said, “Eh.” They’re really famous people. It’s not a complete mystery that they already have [one] written for Jane Fonda, she’s 78…

I think [the NYT] is evolving a bit as an institution. They sort of think about what is interesting to their audiences and how that interest can be fulfilled, and obviously who they have an advance on is something everybody is interested in.

"I’m in the car on the way into the newsroom, thinking ... 'Oh please, somebody huge! Let’s get some huge movie star to die today!'"

NFS: When you filmed the reporters as they interviewed the survivors, did they have to explain the documentary project to the people they were interviewing?

Gould: Yeah. And we got really lucky that they said yes.

NFS: So Bruce would call up the relative of William P. Wilson, say he’s writing the obituary, and that there’s a documentary about him writing the obituary?

Gould: [laughs] Yeah, exactly. And I was sitting there with my tongue between my teeth, just like, “Oh my God, please let this go OK.” And of all things, she said her husband would have been proud.

NFS: I guess it’s fitting, because he worked in TV.

Gould: Yeah, exactly. It’s funny, because we knew we were going to be filming Bruce Weber writing an obit. And I’m in the car on the way into the newsroom for a shoot, and I’m thinking–this is a terrible thing to say–“Oh please, somebody huge! Let’s get some huge movie star to die today so that we have something interesting to people for Bruce to cover!” And instead we had an unknown, which is 70 percent of the obits that the New York Times writes, about people who nobody has ever heard about before. In truth, him writing the obituary of William P. Wilson was a great thing to happen, because it’s so exemplary of what they do on a daily basis and it’s so exemplary of how drawn-in people can get to a story of someone they’ve never heard about before. And then the further idea that he had to do with media and the way media is covered and how that intersects with culture and influences culture was a nice meta-thing going on. We were very fortunate with the way that evolved.

"When we showed it to the Times, they were like, 'What was that?'"

NFS: I’d love to hear more about how the editing style for this film came together. The opening sequence where footage of all these different lives is being stitched together without context, I found that so striking and emotional.

Gould: From the very beginning, the film’s editor [Kristen Bye] was involved in every single decision in the editing room. Our thinking was that, people can watch this movie and learn about X, Y and Z and how they do that and get interesting facts, but we thought what would make the film profoundly more powerful was to then bring those ideas and those feelings into the individual viewers that were watching and to let them feel that sense of nostalgia and history and of generations turning over and just how fast time passes by, and the little things our culture does to mark moments within that avalanche of contemporary history. We felt like a way of bringing people in would be to go through the Prelinger archives and find these old home videos that look like the ones so many people have.

What we tried to do [with these videos] was, in these opening and closing montages, where we get really meta and tap into the history of the century and everybody that lived in it, we wove in our subjects, just to remember that in this huge, pointillist map of history, the people we learn about in the film–the rower, the aviatrix, the typewriter repairman–they were all little points on that map.

But I also think it makes people see an individual before they became whatever they became. You should look at that and see a person’s future. So the idea with that was to turn time around. It was a universal way into that sense of nostalgia and passing of time and what the future may hold and what we all may become and what we all may remember.

When we showed it to the Times, they were like, “What was that?” To them it was out of left field, because they were expecting just a portrait of them. And it actually furthered our conviction that to viewers, this had to be personal in some way and had to resonate what was happening to them in their lives, not just the writers and reporters.

"When I first had the idea of making this film, I said to myself, 'Let’s use this as an excuse to dust off footage that, for any other reason, might never see the light of day again.'"

NFS: How did you actually get the footage of the real people?

Gould: We worked with this amazing archivist out of California, who had just finished up Selma and did a lot of other great features with archives: Milk and The Good German and Good Night, and Good Luck. He was so excited about this. In a lot of ways a project like this was an archivist’s dream. Once we narrowed in on which obituary subjects we were going to try to look at, he started to find whatever he could on these people. And whatever he came back that was the most compelling and the most beautiful helped us make our choices as to which ones we ultimately used. And none of these people are really famous, so he found this footage mostly in the basements of CBS affiliates in, like, Madison, Wisconsin. Half of it came from overseas, and some of these were tapes that have been sold time and time again. He was like a private investigator, practically.

When I first had the idea of making this film, I said to myself, “Let’s use this as an excuse to dust off footage that, for any other reason, might never see the light of day again.” Who’s going to look at this striptease of Candy Barr? That’s just lost. We loved the idea of going to the weirdest places in the most faraway corners to resuscitate stuff that’s so interesting and so forgotten.

"We never got sick of the people we were covering. We would edit these sequences over and over again, and they just never got old."

NFS: I was watching your film a few weeks after a friend of mine died–

Gould: Oh no, I’m sorry.

NFS: But it was very touching, when you show this montage of the writers reading their own prose, and you show footage of all these different people throughout history. I started tearing up. It had nothing to do with my friend whatsoever. But I still felt a very strong connection to that sequence and those lives.

Gould: We never got sick of the people we were covering. We would edit these sequences over and over again, and they just never got old. We really fell in love with them. And I think one of the reasons why I also get sort of choked up in that sequence you’re describing, when they’re reading their own words–you hear just how much attention and care and dignity was applied in the writing of those lead paragraphs of these people by a stranger. There’s something incredibly comforting about that. Even when you’re gone, in many cases, somebody will find the best version of you and write something really beautiful. And it will be there for everyone.

To learn more about Obit, visit its Tribeca profile page.

Be sure to check back for more coverage of Tribeca 2016.