How Pasolini Uses Eye Contact to Move His Audience

Pier Paolo Pasolini made supremely artful use of eye contact, giving transcendent meaning to his films.

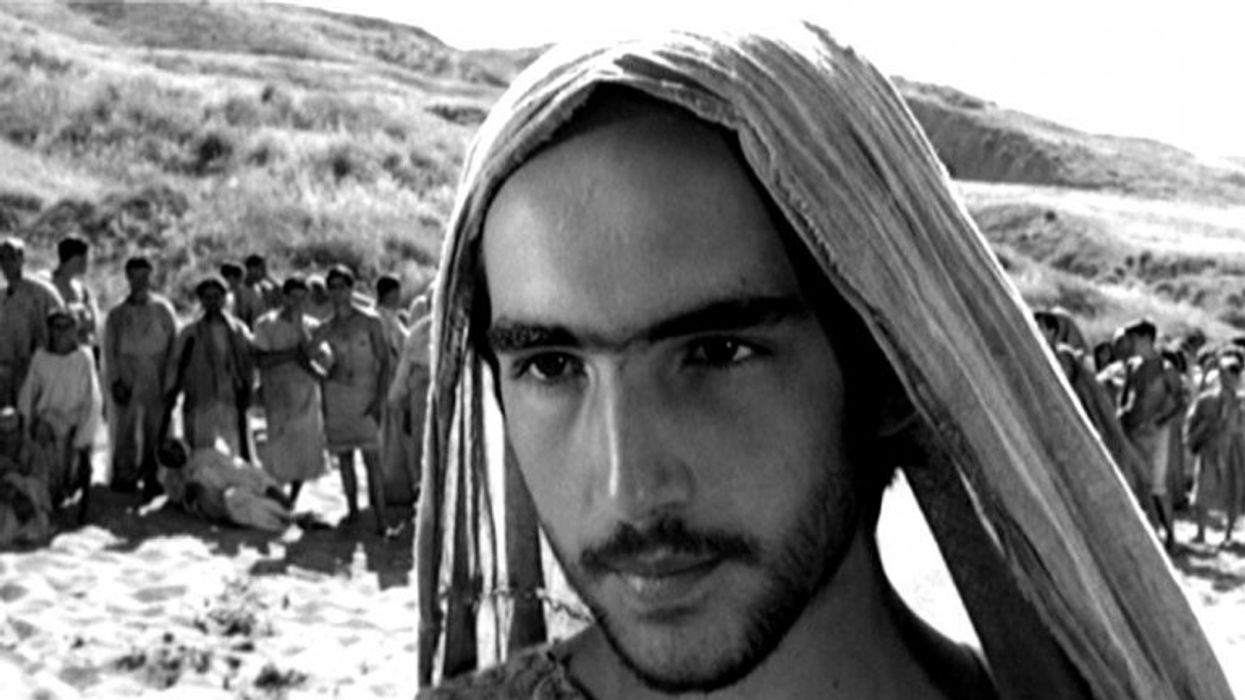

Italian filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini was a polarizing figure during his brief, prolific career that was ended by the mysterious circumstances of his death in 1975. From the restrained beauty of The Gospel According to St. Matthew, to his final film, Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom, he was a singular force in world cinema, producing works of great beauty as well as outrage (caveat: Salo, his adaptation of the Marquis de Sade's scribbled monstrosity is by far the most disturbing film I've ever seen). Daniel Mcilwraith of Fandor meditates on his use of the close-up is a quiet master class in restraint in this video essay:

The filmmaker himself said, "the eye of the camera always manages to express the interior of the character." Keyframe notes that there is always "something unnerving, yet often playful, about making eye contact with those on screen," and that, in Pasolini's films, "Flirtatious smiles, looks of distain, and vulnerable glances all are captured in the character’s eyes by the eye of Pasolini’s camera."

"The eye of the camera always manages to express the interior of the character."

Cinema is, in a pure sense, the art of capturing faces. The human face is so powerful that many consider the close-up the most important shots in film, more so than any set-piece, complex long take, or epic battle. The eyes, the contours of a face—these are the things that make a star. Academics even attempt to quantify an actor's success by the number of times the rhythm of medium shots (the most common shot in films) is interrupted to show their face, alone.

Pasolini's faces are often "confrontational, breaking the barrier between screen and spectator," as this remarkable moment from his quiet, naturalistic version of The Gospel According to St. Matthew demonstrates. Though an atheist and communist, he was not a didactic filmmaker, just as the Jesus of his film is never, what Bosley Crowther of the New York Times calls, a "transcendent evangelist in shining white robes, performing his ministrations and miracles in awesome spectacles." Rather, he let the eyes and faces of his actors communicate all we need to know, and every filmmaker can learn much from this singular artist, a man cut down at the height of his artistic powers.

Source: Keyframe