Watch: How French New Wave Changed Cinema and Created the Auteur

Godard, Truffaut, Resnais, Varda, and other pioneers of the French New Wave movement changed cinema forever.

[Editor's Note: This video essay, a collaboration by Press Play and No Film School, is the second in a series on film movements, their histories, and their enduring influence. Familiarity with movements of the past is crucial to the understanding of current cinematic trends. Watch the first film in this series, on German Expressionism. The following introduction was written by Max Winter.]

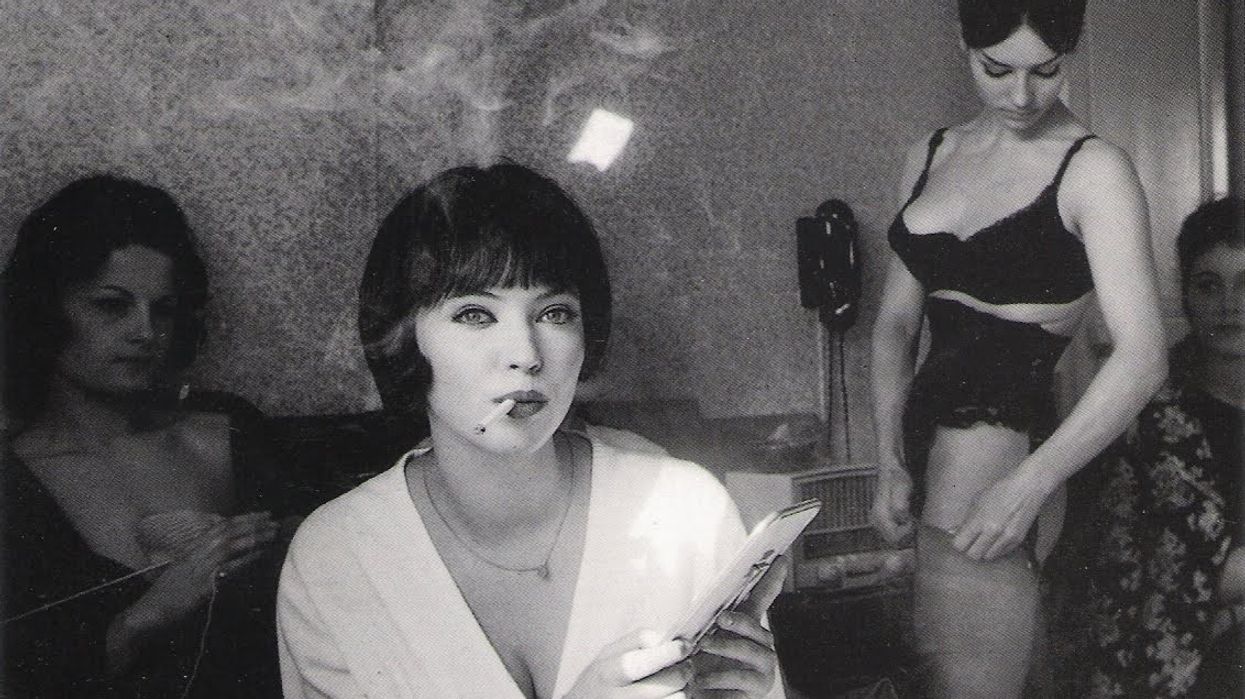

Ah, the French New Wave, the film movement on which many young cinephiles cut their teeth. Its hip, moody, black-and-white stories of love, violence, ennui, and social strife provide a perfect entrance into the private-made-public world of cinema.

The remarkably detailed video essay below both gives us the history of the movement and explains why its disjunctive essence has been so important to today's filmmakers. Watching it might help to explain where our Wes Andersons, Jim Jarmuschs, and even our Charlie Kaufmans came from.

The French New Wave movement began as a result of a sea change in French cinema brought about by the end of World War II, which ended Nazi censorship in France and exposed French viewers to many American and British films they hadn't seen before, such as Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles, as well as French filmmakers like Jean Renoir, all of whom were previously banned.

The movement's founders believed firmly that each director was the auteur of each film, and that large studios could not lay claim to a film's identity.

A group of critics, many of whom published in the seminal journal Cahiers du Cinema, proposed a new cinema that would break with the story-bound principles of past films and explore the potential to which one could play with film structure—and what effect that would have on the viewer. Perhaps more importantly, the movement's founders believed that each director was the auteur of each film and that large studios could not lay claim to a film's identity.

Among its primary practitioners were Francois Truffaut (The 400 Blows) and Jean-Luc Godard (Breathless, Masculin Feminin), who made films which, with their jazzy, relentlessly improvisatory eloquence, immersed us. They also pioneered techniques and approaches that are now standard devices for imaginative filmmakers.

One of the most important foundations of the French New Wave was an interest in and respect for realism; few sets were constructed for these films, and most of them were made on location. This enabled the filmmakers to work with relatively small expenses. The famed Left Bank of the movement, whose practitioners included Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda, and Chris Marker, took this idea even further, building some films almost entirely out of photographs and other factual, research-based materials. For example, Chris Marker's La Jetee, considered by some to be (at least) a progenitor of the video essay, is made solely out of a series of photographs.

The French New Wave pioneers pushed the limits of cinema technique. In Godard's special use of the jump cut—where time passes with each successive cut—the space between the cuts suggests a wealth of information. This technique has influenced directors for decades. The long take was also a favorite of the New Wavers, given that it could allow the viewer to immerse himself or herself in a location, the mise-en-scene, or a character's face.