'Search for Revelations': Invaluable Cinematography Advice from DP Kirsten Johnson

Seasoned DP Kirsten Johnson gives some of the best cinematography advice we’ve ever heard.

Kirsten Johnson faced a room full of fellow filmmakers at the Camden International Film Festival and held up one of her most important tools. A camera? A gimbal? No. A simple water bottle. “The biggest, most important thing I know as a cameraperson,” she told the assemblage, “is how to manage my water intake, and I'm really serious about this.” She the proceeded to shimmy over the desk that she was behind and join the audience.

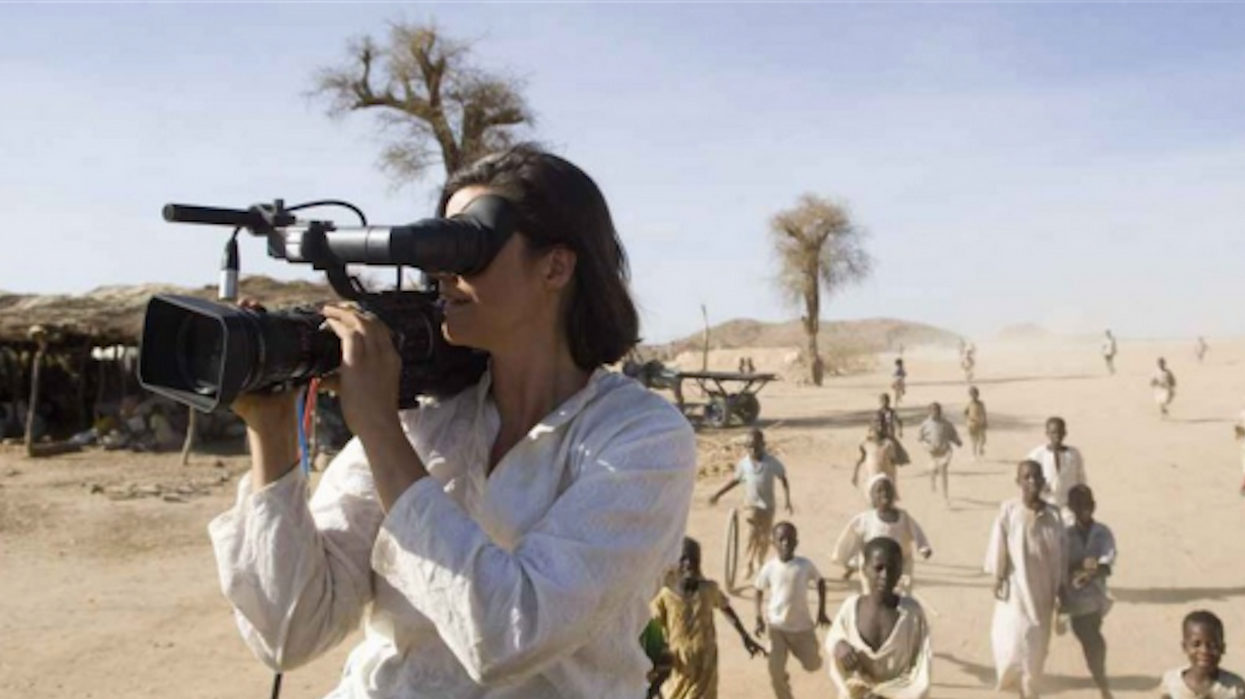

These two tenants—staying hydrated and knowing how to negotiate her body in a space filled with other people—are cornerstones of Johnson's long and storied career, during which she has shot over 25 films for the likes of Laura Poitras and Michael Moore.

Some of these stories are finally being displayed from Johnson’s own perspective, rather than in service of another director’s vision, in her new feature documentary, Cameraperson. (See our interview with her about the film from Sundance; it also won CIFF’s Harrell Award for Best Documentary Feature.) An object lesson in what happens outside of the frame, Cameraperson is a must-see for any documentarian.

Here are some of the best lessons we gleaned from Johnson at her CIFF masterclass:

Seriously, stay hydrated

"This is your big takeaway from the day, this bottle of water and my body," Johnson announced dramatically. She pointed to the myriad tense, long-term situations that camerapersons can get into in which you can’t move for hours at a time. You need water to function, but at the same time, "you must only drink as much water so you will not have to go to the bathroom ever. This is an acquired skill. Basically, you learn to calibrate how exactly how much you need to take in."

There are many things that a cinematographer needs to calibrate to stay present in the moments that they are filming. "You need to be hydrated," Johnson acknowledged, "you need to have some kind of nourishment, and you need to be monitoring your own emotional response to what's happening in the situation. That's a very complicated set of issues."

Understand yourself and your subjects simultaneously

Johnson showed the group some very sensitive footage that she had shot of female military personnel who had survived sexual assault by fellow soldiers while on active duty. She apologized for not warning us first—but, she asserted, this is exactly what happens to you as a shooter.

"You're brought to a place," she said, "you're picked up from the airport and start hurrying, and you get into a room and suddenly you're hearing things for the first time as you are trying to film them."

This challenge is especially pronounced if you're both the director and the cameraperson (a feat which Johnson deemed "slightly crazy"). Among all the things you have to keep in mind while shooting, being present with your subjects while also thinking of the big picture of your film might be the most important. As Johnson described it, “You’re managing everything that's going on inside of you, as you're trying to understand what's going on inside of other people.”

Let truth trump aesthetics

It probably goes without saying, but for most cinematographers, image is paramount. For Johnson, this doesn’t mean that a standard definition of beauty has to be your top priority.

"On an aesthetic level, we dream of beautiful, golden shots—sunshine, beautiful people that have beautiful skin...and then you get into a situation and everything is ugly to you," Johnson mused. "It's an ugly room, ugly furniture, your subject’s face is getting blotchy as she's talking to you….”

But in those situations, Johnson advised, simply take a breath and remember that everything in your frame is helping to tell the story. In the case of the subject’s "blotchy" face, "this person is talking emotionally about something deeply important to them; the way her face was becoming red is telling the interior story of her body."

Work in teams

Johnson acknowledged that filmmaking demands ego. "We all have crazy hubris like, 'We're going to build something out of nothing and make a film,'" she said. But she also knows that it usually takes teamwork to make a good film happen, particularly because the challenges of being a director are very different from those of being a cinematographer.

"I ask of you to collaborate in the world because there's a lot going on when you're making a film," she implored. "You can help each other.”

Of course, these partnerships don’t come without hitches. "The collaboration is such an intense thing," she stated. "There's so much demanded. You think that you're doing everything and nobody else is doing anything, when and in fact they're doing it as much as you are." The entire audience laughed knowingly.

Our footage is “a mirror of us as filmmakers as much as it's a mirror of the people who we are filming.”

So how does Johnson make it work? As a cameraperson, she said that she prefers to "talk to a director about what they care about, what they're trying to do, and sort of immerse myself in the things that they love and what are they trying to imagine. Then I don't need to be told anything—I don't need to be told what lens to use, I don't need to be told where to stand. What I need to understand are the questions that they're involved in."

Search for moments of revelation, but intervene carefully

Once Johnson generally knows what she’s looking for, her primary job is to be present in a situation to capture the small, subtle moments and signals that characters are giving. She elaborated, "I think that what we're searching for as camerapeople are these moments of some form of evidence and revelation that are different from what is known. That search is what pulls us forward."

This also begs the question of when, or if, a shooter should intervene in a scene that feels problematic. Johnson admitted that this is a constant struggle for her; Cameraperson pulls back the curtain on several moments when she clearly felt torn about whether or not to become an active participant in the scene she witnessed.

One of the most harrowing of these scenes involves a dying baby in a Nigerian clinic. Johnson audibly wonders whether or not to beckon a midwife who has stepped away. She admitted ruefully, "I go back to hubris—thinking you know what to do. There is nothing I could have done for that baby and nothing the midwife could have done for that baby in that situation. What we learned after the fact was that the hospital pulled off all kinds of resources to continue to try and save that baby because we were there filming."

"A lot of times, you're a clueless outsider projecting all kinds of things onto the people you're filming and you're telling a false tale."

As such, unintended consequences can be positive. When she was making Cameraperson, Johnson learned that the father of that same baby is a modern Imam in what has become a Boko Haram village. He told human rights workers in Nigeria that he wanted to stay in the village to defend the rights of women—despite threats and extremism—because Johnson had stayed with him years prior while his baby was dying.

Ultimately, stick with your gut instincts and the information you have at hand to determine the best course of action. However, if you do decide to intervene in a situation that you are filming, tread lightly.

It matters where you put your body

One subtle form of intervention can simply be how you move in the space with your camera. Often times, like when Johnson was filming the military rape victims, you have to absorb someone else’s trauma while getting the story beats necessary for your film—a complicated negotiation. Of that specific scene, she noted, "My capacity to actually move in that space was incredibly limited and strange, where I would start to get close to someone and see them flinch, but then when they were speaking their testimonies, they wanted the camera to be there."

The challenge: you need your subjects to trust you, but you also need to have freedom to move. "In a certain way, you can't leave them," Johnson continued. "You made some sort of an [unspoken] pact with the person, that they're going to reveal the most terrible things of their life. You're here and they’re talking and suddenly you realize, if you move, it is a breaking of this bond. Yet, you're trying desperately to think of, 'how am I going to cut this into a sequence?'"

She gave an example of how a cameraperson's choices might affect a scene. "Suddenly, you see someone pressing their fingernails against their arm and you can see they're hurting themselves," she said. "You then have to decide if you either want to potentially change their behavior by shifting your placement or capture it from across the room with the long lens. By merely making your subjects aware that you have noticed something, you can change a whole scene."

Your subjects will always be surprised by the final product

One crucial aspect for any documentarian is building trust with our subjects. Johnson drew a distinction between the trust that’s created during filming—for example, that you, the cameraperson, will respect that person’s space—and the trust that the finished product will be what they anticipated. When a film comes out into the world, “it will be a completely different thing than you imagined as the director, and it probably will be a completely different thing than I imagined as the cinematographer, and it will definitely be a different thing than the person imagined," she said.

By way of example, Johnson told an anecdote about her current project, which involves filming the Soloway sisters, Jill and Faith. Jill’s show Transparent is based on their own family story; Johnson is now capturing their real lives, behind the scenes of the show. Johnson recalled, "They're trying to make this thing together and I'm somewhere in the equation, I don't even know where. Their two different perspectives on what the footage is is so radically different, I literally started laughing. It could not have been more polar looking at the scenes of themselves."

We need to prepare ourselves and our subjects for a wide range of potential reactions. But it’s not just your subjects who are exposed through footage—it’s also you. According to Johnson, our footage is “a mirror of us as filmmakers as much as it's a mirror of the people who we are filming.” She warned fellow filmmakers to be aware that common purpose can quickly turn into deep misunderstanding.

You can’t know everything

One of Johnson’s most profound statements of the afternoon: "I guarantee you, all of you think you're making a film about something, and you will make a film about something else."

This idea circled back to her assertion about the hubris of filmmaking. It’s not just that we believe we can adequately and truthfully tell other people’s stories, but that we have to make decisions about what to leave in and what to take out—decisions which get skewed through our own perspectives on the world.

"We think we know what a film can be and what the world needs to be, and then we're encountering the evidence and complexity of what it actually is," she said. This gets compounded by the fact that we have such intimate relationships with our subjects. "Your naiveté of the other person's reality is acute because sometimes you're really deep in. You can see someone's eyeball because the camera lens can take you so close."

Johnson paid heed to the fact that it can also serve your story well to be an outsider—for example, if you need a critical eye to expose corruption in a situation where the insiders can't talk about it. However, she cautioned, "A lot of times, you're a clueless outsider projecting all kinds of things onto the people you're filming and you're telling a false tale."

"What do we do with this moment in history that we're in? Why are we all trying to make films and why are people letting themselves be filmed?"

Keep asking questions

In order to combat the danger of "telling a false tale," Johnson advised to continuously analyze and gain perspective on your own work. In fact, that is part of why Johnson made Cameraperson.

"In some ways," she said, "the gesture of making this film is simply to say all of this mattered to me. It still matters to me, and I am holding up the incompleteness and inadequacies of it and the struggle of it and trying to bring the discussion into a larger place.” The discussion that she is engaging her fellow filmmakers in, along with her audience at large, revolves around the very nature of making media.

Johnson may as well have been speaking directly to the No Film School community when she declared, "It's amazing that all of you are filmmakers. It's amazing that everybody in the world has a camera. What's going to happen? We're all struggling with this thing. What do we do with this moment in history that we're in? Why are we all trying to make films and why are people letting themselves be filmed?"

By transparently sharing her process and continuing to ask questions, Johnson has done a service for our industry, allowing both novice and veteran filmmakers to learn from her impressive career.