Dying Onscreen: 'Badlands', 'Bonnie and Clyde', and American Violence

Penn's 'Bonnie and Clyde' and Malick's 'Badlands' both explore American violence, but in profoundly different ways.

America has been, since its birth, a nation steeped in violence, and film, that most profoundly American art form, has never shied away from this fact. For decades, the infamous Hays Code had kept a lid on sex and violence in the movies, but starting in the late 1960s, Hollywood began to produce films that depicted onscreen mayhem in a more explicit way that had never been seen before. The first, and most famous, of these films, was Bonnie and Clyde.

Bonnie and Clyde seems to be a classic case of a film wanting to have its cake and shoot it, too.

Bonnie and Clyde and Hollywood Glamor

Until 1967, and the release of Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde, actual bloodshed was seldom shown onscreen. As Thomas Mazzucco writes in his essay, "Filming a Revolution: The Birth of Graphic Violence in Bonnie and Clyde," the "severity of injury was usually just implied through moans or other acting techniques" up to that point.

Not so in Penn's film, where, in the climactic scene, the titular duo is gunned down at the hands of the villainous Texas Ranger Hamer and his goons. The scene deployed over 1,000 squibs, the most of any film up to that point. Of the violence, Mazzucco writes, "Penn...show[s] the true devastation violence brought in reality...[the screenplay] mixed humor and comedy with romance to offset the great violence." And the director himself has been quoted as saying, "it seemed to me, that if we were going to depict violence, then we would be obliged to really depict it accurately—the kind of terrible, frightening volume that one sees when one genuinely is confronted by violence."

While some of the film's apologists claim it is an allegory for the Vietnam war, this strikes me as a case of protesting too much, not least because of the comic tone of much of the film—it displays a profoundly unserious treatment of violence. Furthermore, the two stars are overwhelmingly glamorous; when contrasted with those with whom they interact, they appear as veritable golden gods among the dustbowl mortals. Bonnie and Clyde seems to be a classic case of a film wanting to have its cake and shoot it, too.

There is something vaguely fascistic in the film's aesthetics. With its scenes of gore and mayhem depicted in a highly stylized manner (i.e. the final scene, with its slow motion and repetitious bloodshed), Penn undercuts his own arguments about obligations to accuracy.

At one point, Jean-Luc Godard was attached to direct the film, and though the movie claims a spiritual lineage to the French director's debut feature, Breathless, when one watches that movie's final sequence, the death of Michel (who is, incidentally, obsessed with American screen legend Humphrey Bogart) could not be further from the tendentious visual moralizing of Bonnie and Clyde, which is, in the end, nothing more than a classic Hollywood blockbuster masquerading as protest film.

The violence depicted is neither accurate nor particularly interesting.

Bonnie and Clyde's subversion is not in the way violence is deployed, because the violence depicted is neither accurate nor particularly interesting. The film is remembered, and justly so, as the movie that burst the levee which had previously held back the blood-dimmed tide of pornographic onscreen mayhem, but really, that's all.

Its legacy can be seen in the countless violent films which followed, though, ironically, a film like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, while certainly more disturbing, is actually less bloody than Bonnie and Clyde and its thousand squibs, relying on camera tricks and editing for effect. Where Bonnie and Clyde fails is in its tone-deaf quality, its failure to understand that depiction is not the same as critique, no matter what the filmmakers would have you believe.

Malick managed to both avoid the clichés of Bonnie and Clyde as well as craft a story far more in line with Breathless.

Badlands and the Myths of American Murder

Seven years after the mayhem of Bonnie and Clyde, Terrence Malick made his feature debut with Badlands. The 1973 film accomplished much of what its predecessor had done. In its depiction of another real-life murderer on the run (the film tells the fictionalized story of teenaged murderer Charlie Starkweather and his 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate), Malick manages to both avoid the clichés of Bonnie and Clyde as well as craft a story far more in line with Breathless and its movie-obsessed protagonist.

Where Bonnie and Clyde is all winking glamor, Badlands is a haunting critique not only of the myth of American violence, but of the way that movies themselves craft myths that are, all too frequently, lived out in real-life.

Based on the story of 19-year-old Starkweather, who, with Fugate at his side (either as accomplice or hostage), murdered 11 people in Nebraska and Wyoming between December 1957 and January 1958, the film depicts with a stark realism a murder spree that was sparked (ostensibly) by the refusal of Fugate's father to allow the two to be with each other.

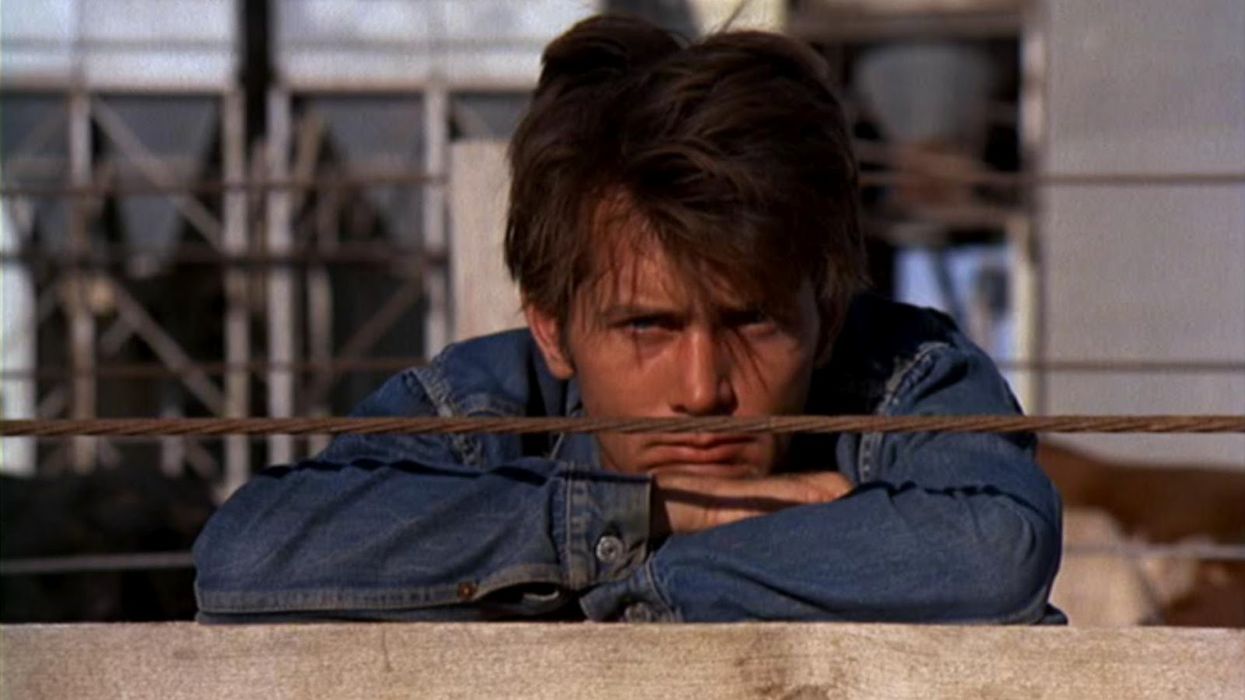

After first murdering a gas station attendant weeks earlier, Starkweather murders Fugate's mother and stepfather (as well as her two-year-old stepbrother), then flees with her when she arrives. Malick fictionalizes much of their killing spree (the names of the characters played by Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek are changed to, respectively, Kit and Holly), but at no point is the story ever glamorized. Contrast the ending of Bonnie and Clyde with the Kit's final run:

While Bonnie and Clyde plays with tropes and genre, pretending to deconstruct what it actually prettifies, Badlands shows what happens when characters live by tropes: The Rebel Without a Cause, The Doomed Lovers, the Innocent Killers, backed into a corner. Badlands takes these myths and explodes them, by refusing to traffic in the romance of murder, and instead showing the actions of characters playing at being in movies.

Badlands is a film about bored American youth in thrall to the myths of Hollywood, the myths of America. This is actualized in the film by Spack's narration, which, with its affectless tone, often belies the mayhem that takes place on screen. In one of the movie's most profound sequences, the two are shown fleeing the fiery wreckage of Holly's house after killing her father, and then taking to the woods to live in a brief idyll of teenage make-believe.

The two films could not be more different, and while both are equally important, their relevance arises from strikingly different places. In Bonnie and Clyde, Arthur Penn takes the story of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker and, through his glamorous surrogates Beatty and Dunaway, crafts a Hollywood blockbuster very much in line with the classic tales of gangsters on the run, pursued ruthlessly by the law.

The difference in Penn's approach is the way in which his antiheroes are depicted as the truly righteous parties, up against the "system" as personified by Hamer and his goon squad, out to viciously murder the Robin-hood like Barrow and Parker, who are only in it to stick it to the man. In contrast, Malick's film depicts a James Dean obsessed teenager who commits murders out of what appears to be nothing more than fatalistic nihilism, a boredom with his dead-end existence.

No one in Badlands dies in slow-motion, and no one dies for any reason at all.

Spacek's narration highlights the unreality of the duo's mayhem, the degree to which they are living out a sort of fantasy, and in this respect, the film is far more like Godard's critique of a Hollywood-obsessed hoodlum. But whereas Godard has a certain winking quality in his film (which, to be fair, is present in many of the director's works), Malick turns his camera on the mayhem with, if not detachment, then certainly not approbation. Like Godard, Malick is interested in the degree to which the myths of Hollywood are lived out by those who watch them, and in doing so, does more to critique the idea of violence as a sort of meme, transmitted by Hollywood, than any moralizing could do.

Bonnie and Clyde and Badlands could not be more different in the way they handle the myth of American violence as perpetrated through Hollywood. But the ethical waters plumbed by Badlands are far more honest, murkier than in Arthur Penn's 1967 love letter to the real Bonnie and Clyde. No one in Badlands dies in slow-motion, and no one dies for any reason at all. Rather than going out in a blaze of glory, at the end, Kit's cowboy posturing ends in a coward's defeat, and in this, is far more realistic than the fatuous martyrdom of Bonnie and Clyde.

While both are important films, in the end, it's Badlands that has something far truer, and more disturbing, to say about American violence and its relation to the flickering images on the screen.