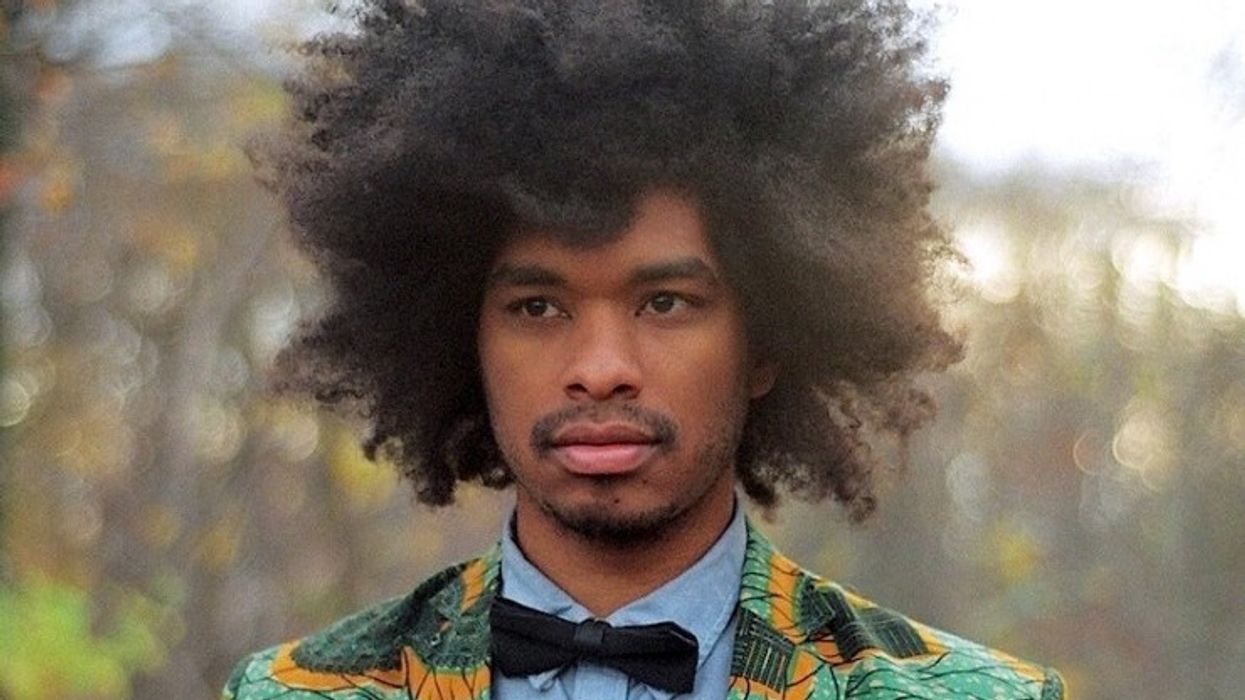

How Director Terence Nance Made a Microbudget Sci-Fi That Left Audiences in Tears

Terence Nance, whose name you will know by heart if you don't already, is a cinematic force.

Terence Nance's feature, An Oversimplification of her Beauty, is his attempt to reckon with femininity as a male artist—a peculiar direction for a debut filmmaker, but perfect for Nance, who is propped up, inspired and beguiled by the many members of his community. Through his work as a producer, critic, cinematographer, director and actor, he's helped change the way audiences relate to black art. Through his short work—Univitellin, Swimming in Your Skin Again and especially his latest, They Charge for the Sun, which played to rapturous approval at this year's Blackstar Film Festival—Nance has beamed beautiful, strong images of his community to audiences around the world. Nance's highly theoretically and deeply intelligent work speaks for itself, but he doesn't stop there. He works tirelessly on behalf of other young black artists, as well.

"Finding the ecstatic moment in the process of making the films and showing them is really elusive."

They Charge for the Sun is a sci-fi film and, as such, something of a departure for Nance. It follows a young black girl, Eve, in a dystopian future where people carry out their lives at night to avoid the sun's harmful rays. We spoke with Nance after his incredible premiere at Blackstar, which found a packed house erupting with applause, laughter, tears, and cries of joy at its final minute, an experience unlike anything we've ever had in a movie theatre.

NFS: What was the funding process for 'They Charge for the Sun'? Did the sci-fi element help you pitch it? Do you think having a succinct idea helps with the funding of new work?

Nance: It was originally a music video that was inspired by a D Propser Lyric "In the future they will charge for the sun." When that music video didn't happen, I was trying to find a way to make it, and through a complicated series of events, the vast majority of it was produced through [film lab] Project Involve so there wasn't a process of pitching it to "financiers" or anything like that. It was just the film I was making as a director in the program, which requires you to make a film. That said, I think the film was under-funded in that everyone in the program, my marvelous producers Kady Kamakate, Ana Souza, Giula Caruso, my amazing DP Andressa Cor, my co-writer Eugene Ramos, and I believe all the above-the-line crew and most of the below -the-line crew as well worked for free or cheap to get it done and lots of aesthetic sacrifices were made to make the film with almost no cash on hand. All that said, if I had it to do over again I wouldn't have made it that way.

In general I don't know how people get "funding" for movies so I can't say what would help in terms of pitching. I don't think the idea matters at all in the quest for funding. I find that it's more about if the person with the money likes you and is attracted to you and your work enough to patronize it.

"I tried to not think of it as a genre film."

NFS: This film is a little bit of a departure for you, being very specifically a genre film. Can you talk about tackling something with a set of guidelines sort of built into it? Did you have to alter your aesthetic approach at all working in the genre?

I tried to not think of it as a genre film, and allow the characters to dictate what the world would be stylistically. Also, it wasn't set in the "future" or maybe I should say "the movie future" or a space that operates explicitly in our collective aesthetic imagining of a dystopian future, which most often is intentionally aestheticized as an impossibility. I wanted the film to feel probable, so I just thought of it as a story that was experienced from Eve's point of view and made aesthetic decisions as If I was her.

NFS: When the big reveal (which I won't spoil for readers) happens at the end of the film, I heard a thunderous applause the likes of which I have never heard in my life. It was incredible, I felt like the love in that room could have lit the city. How did it feel to know that your work had had that much of an impact?

Nance: It's hard to describe how it felt. It was a fundamentally indescribable moment. I think it's the closest thing a filmmaker can feel to what a standup comic might feel if they set up a story-based joke for like 10 minutes and it really lands. Or when a musician works an audience into a communal ecstatic moment. I think, as an artist who makes static work (stuff that isn't "live"), finding the ecstatic moment in the process of making the films and showing them is really elusive, so when it kind of landed so emphatically like it did at the screening it overwhelmed me; I teared up a bit.

I also think the response was less about the film and more about the audience at Blackstar, and the cross-section of black life that we represent. It's about us and where our experiences meet, and the response in that room was this strange, and unexpected moment of universal commonality. Like a moment when a lot of people are ecstatically on the same page not just because of what the movie is saying but because of what is going on outside the theater every day.

"It's about us and where our experiences meet, and the response was this strange and unexpected moment of universal commonality."

NFS: What do you think it is that made that moment come alive and turned that movie theatre into what felt like a wedding, a graduation and a mass all rolled into one?

Nance: I can't answer that without a spoiler but I guess I don't have any intentions with the work in that way. I don't have specific intentions about what anyone would or could take away. I'm more curious about how people respond and remain open to what those responses bring out in me.

NFS: You helped make one of the best films I saw last year, Naima Ramos Chapman's And Nothing Happened. Do you have any other projects in the pipeline about which you're particularly excited?

Nance: I am a partner of a production company MVMT which I run with Director/Writer/Producer Chanelle Aponte Pearson, and her first narrative directorial project is called 195 Lewis. It's a series that we are releasing online this fall. It's played at many fests, including Rotterdam, OutFest, and Blackstar to name a few.

In post production, we have Mariama Diallo's first feature African Scramble, and Naima's follow up short to ANH called Piu Piu. In development, there's Tayarisha Poe's first feature Selah and the Spades, which just finished the Sundance Labs. Naima is also in development on a series called Groupchat.

I hesitate to call what I do with younger filmmakers "mentorship" because I think that implies a one-sided dynamic in which I impart all the knowledge. I collaborate with lots of unbelievably talented artists and these collaborations are mutually beneficial to them, MVMT, and myself as an artist. At the end of the day, when I was trying to make my first feature, I felt very alone and, more specifically, I did not have any relationships with filmmakers who had done it before and were willing to help me make my film, but this was not for lack of trying. Also, I should say that in the art world I had a few very helpful mentors so I knew what I was missing on the film side.

After going through that, I made a promise to myself that at whatever point I had any access to any resources in the film industry, I would make sure to do everything in my power to help as many people as I could who were feeling the way I was feeling when I was just starting out. All that said, I'm not particularly good at it and my methodology needs lots of refining.