On Land and Sea: How Aquatic and Grounded DPs Seamlessly Collaborated on Simon Baker's 'Breath'

Established actor Simon Baker relied on collaborations with two experienced shooters for his feature directorial debut.

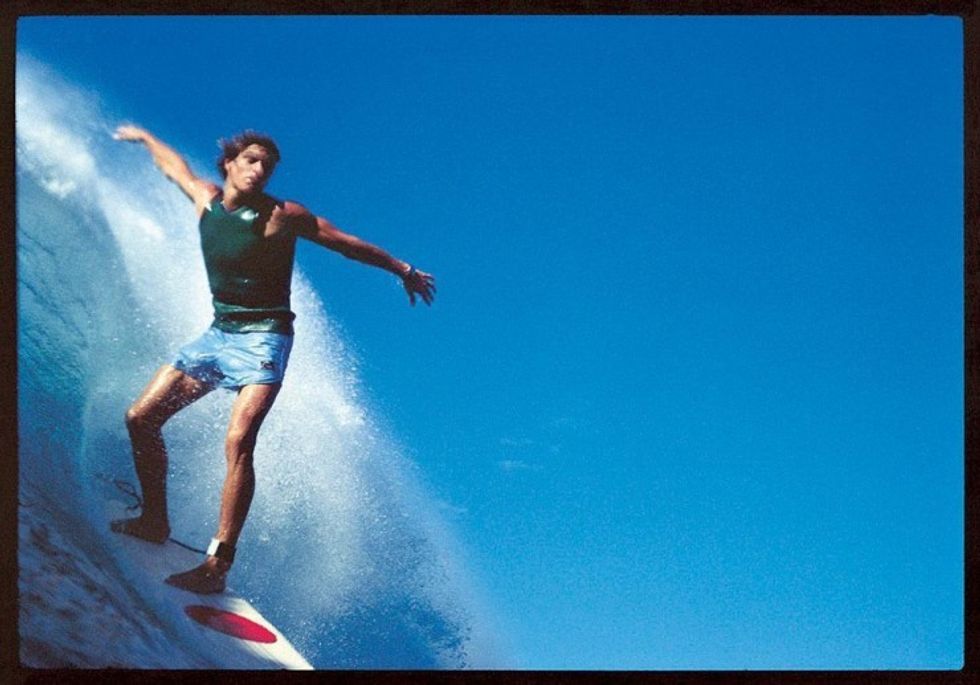

One director, two DPs, and a beautiful film. Breath is an adaptation of Tim Winton’s award-winning and internationally bestselling novel, a bildungsroman about two young surfers on the Australian coastline, set in the mid 70’s. It’s not just a great surf movie; it’s a compelling, visually radiant story with deeply realized characters. Breath premiered to critical acclaim at TIFF 2017 last week.

Even if you aren’t familiar with Simon Baker–the Australian, Golden Globe-nominated actor-turned-director who made the film, both as actor and director–you’d probably recognize him. As an actor, he has performed in The Devil Wears Prada, The Ring, LA Confidential, to name just a few, as well as in TV series including The Guardian and The Mentalist–both of which he has also directed. Breath is his debut as a feature film director.

“Each film is its own journey. If you pay attention, you can learn a lot.”

The result is stunning. Much of the book, and the film, takes place in the ocean as well as on land. To satisfy this duality, Baker enlisted the two best DPs he could find: Marden Dean, an award-winning, mostly land-based cinematographer who has shot 24 features including Fell, The Infinite Man, and Boys in the Trees, all gorgeous; and water cinematographer Rick Rifici, one of the world’s most sought-after camera wizards. Like Baker, they’re Australian, and all three are surfers.

This threesome is what makes the film shine. In an intimate industry talk at TIFF, they revealed how their Director / DP collaboration evolved, what cameras and lenses they chose for the project, and how they managed to stay in sync.

Learn to Adapt

“Each film is its own journey,” Baker declared. “If you pay attention, you can learn a lot.”

A mess of blond curls, Baker was in full surfer-dude form–but as soon as he spoke, he upended his image. Just as the film proved to be far more profound than your average "surf movie," Baker is far from the beach bro stereotype–and as both Dean and Rifici were quick to agree, he knows how to collaborate.

“Most of what I know–the importance of teamwork, the importance of flexibility–comes from my years as an actor,” he explained. “I’ve always been a sponge on sets.”

One of the lessons he learned was that there is no single approach to directing. “All directors approach things differently,” he told us. “Some are more visual than others. I’ve learned as much from first-time directors as I did from Martin Scorsese, George Romero, Ang Lee. The one consistency with all of them is that when you’re directing, you’re the curator. You have to embrace the fear, the doubt. You don’t let those emotions choose the music for you–but you do take them on the road trip with you. You have to learn to adapt.” He smiled. “It’s pretty simple: each situation is a meal. If you don’t have good tomatoes, don’t do a tomato dish.”

"Each situation is a meal. If you don’t have good tomatoes, don’t do a tomato dish."

Baker paused, reliving a lifetime of chaotic sets. “Film production–and TV, especially–moves at such a high speed. So you surround yourself with good people, you try to make them your allies.”

“And you communicate. That’s the key.” Baker’s voice was emphatic. “That’s why I do group story time: I say ‘Here’s the scene we’re shooting, here’s how it fits in the story.’ When you do that, you see the crew get more enthused, they bring a part of themselves to the shoot. The excitement of that collaboration, when everyone is invested…You can feel that in a movie after the fact.”

Mind-Meld with Your DP

“The way I see it,” Baker asserted, “my responsibility as a director is to honor the filmmaker in everyone who’s on set. And for me, that starts with the DP.”

“I’m lucky. I’ve gotten to work with some of the best. I just hover around and watch how they work.” Among the DPs he has worked with: Frederick Elmes (Blue Velvet), Peter Suschitsky (The Empire Strikes Back), Mauro Fiori (Avatar), Dante Spinotti (LA Confidential). “The great ones are flexible and confident,” Baker continued. “They approach each project for what it is; they don’t bring the same rules to every movie. And they’ve got a depth of experience that prepares them for the unpredictable.”

"If you can’t communicate your ideas to a cinematographer, how do you get them to find the stuff you love?"

A long-time photography and cinematography obsessive himself, Baker likes to nerd out about lenses. “My DPs love it when there’s an actor who’s frothing about lenses. They don’t get that every day.” Frothing with technical jargon himself, Baker stopped in his tracks, eyes searching the crowd. “I don’t know how many people here are into lenses...” *Crickets from the crowd* Baker cut the silence: “YOU SHOULD BE!”

After a laugh, Baker continued. “As a director, if you can speak the same language as your cinematographer, that’s a godsend. And that goes for anyone else in the crew. If you can’t communicate your ideas to a cinematographer, how do you get them to find the stuff you love? You experiment, they show you different lenses, you’re finally like ‘Oh, I like that.’ Then it’s lunchtime. Next thing you know your budget’s gone and you haven’t got a film.”

So what if you’re not a lens nerd? How do you mind-meld with your DP before production begins? Baker and his DPs eyed each other: who was going to answer that one? Once again, Baker took the lead. He recommended Artemis, the Director’s Viewfinder iPhone app … along with what he called ‘communication’s best friend’: preparation.

Prepare Your Vision

The first part of their prep was Tim Winton’s book. It appealed strongly to Baker because he had lived it. “I knew all the characters in it, I understood them because I had spent close to 38 years surfing. I thought someone would probably adapt this book, and figured it should probably be me.”

Winton’s book also moved him because of its supremely visual language, and that led him to his choice of cinematographers: Marden Dean on land, and Rick Rifici in the ocean. They were already familiar with each other’s work–and as soon as Baker told them his vision, they said yes.

“We didn’t want to make what we call ‘surf porn,’” Dean explained. As lifetime surfers themselves, he and Rifici were sick of the ‘Hollywood surf movie’ aesthetic. “Everyone’s always after the pretty blue pictures, the big waves,” Dean continued. “But then in order to tell their story, they have to go back on land. It’s like they’re making two different movies.”

Instead, this trio’s goal was to capture Australia’s character: not just the wide brown land and red dirt of the outback, but the look and feel of the coastline…with characters who transitioned seamlessly in and out of the water.

“That was why we loved Tim’s book,” Baker clarified. “He writes incredibly beautifully about the alluring quality of the Australian landscape, the harsh brutality of it, and the individual’s place within it.”

"I didn’t want to have any finicky lighting setups, it was very free form."

“Our film does have a few pretty blue waves,” Dean admitted. “But the vision Simon wanted was to put the viewer in the water. As a surfer. So we did that. The result: ‘surf porn vérité.’"

Rifici hid his smile with a nod, “For me, this was special because I got to go totally abnormal,” he confirmed. “We’ve seen every narrative film that ever had surfing in it, every obvious gadget shot by a guy on the back of a jetski, framed to torso. And we’re always able to spot the fake parts, the lack of authenticity.”

Authenticity was their mantra. “The three of us have never found a film like the stuff we see as surfers,” Baker avowed. “The things we feel: the goosebumps, the tweaks of the senses, the smell of that first morning of summer. Our goal was to capture the things we take for granted. The stuff we glimpse all the time.”

“That was true for on land, too,” Marden added. “We wanted a naturalistic look, to evoke different moods. I didn’t want to have any finicky lighting setups, it was very free form. I’ve done a lot of docs in my time, so I really enjoy being able to evolve a shot and experiment.”

Choose Your Tools

“Planning, planning, planning,” Baker repeated. “That was how we made Breath.”

He laughed. “Before production, I started flooding Rick with images,” he recalled. Rifici nodded, remembering. “There’s this progression that happens in Breath where the water stuff gets more complex. So I kept sending him compilations of different images, Tom Lake, Ron Stoner, early ‘60s surf photography. The film develops over time into this John Witzig style.” (Witzig was a seminal ‘60s-‘70s Australian surf photographer.) “And I did this with Dean too.”

Then came locations. In order to prepare for the environmental changes they wanted, the trio visited the locations early and often–and with that came technical planning.

“We originally thought we’d shoot this on super-8,” Baker confessed. “Which, looking back, is an unreal, absurd idea. But out of those absurd ideas, some sort of growth always manifests. So don’t be afraid of those absurd ideas, use them to explore further, deeper. And be patient: the process takes time to grow and develop.”

"At the time every single movie was anamorphic, so I was like 'Fuck this.'"

Their main problem was beauty. “It was hard setting frames because the locations we chose were so vast and beautiful, we didn’t want a camera to interfere. You could see it all so much better with your eyes!” Eventually, they solved it with lenses. They used the ‘Frame Grabber’ website to test out different looks, they debated anamorphic vs. aspherical. “At the time every single movie was anamorphic, so I was like ‘Fuck this.’ Plus the landscapes were so massive, aspherical ended up being the right choice.”

“That improved our optical quality,” Dean elaborated. “It gave us edge to edge sharpness, very little flare, everything extremely precise. Aspheric made everything feel more alive.”

Baker nodded, clearly pleased. “We took a lot of photographs,” he grinned. “And it made a huge difference. When we finally went back to shoot a specific location, I’d find photos on my phone from the year before. And be ready to shoot.”

Their next challenge was underwater. Rifici shot on RED Dragon, in 5K–“so we could show all the particles in water, instead of that crystal clear swimming pool look,” he explained–and most of the time, he used a 25 mm lens. “When you put a lens underwater, it magnifies everything by .75,” he clarified, “so 25mm is more like 35mm. And we chose quick S4 lenses: they’re designed to be shot with film, they give you a much creamier, softer look. They’re big lenses, heavy to swim with–and you have to shift the camera with your arms to change focus, because you can’t have a focus puller underwater. But the results are worth it.”

Rifici shrugged: underwater is the world he chose. “You can only be so prepared, as far as your equipment goes,” he added. “You have to make the most of it on the fly, capture what you can, because a shot might only happen once.” He paused, eyeing his teammates. “Plus it’s lonely down there.”

Dean and Baker both laughed. “We kept ya company, mate.”

Keep It Real

Part of their prep time, of course, meant finding the right actors: in this case, non-actors. Baker found two teenage surfers, Samson Coulter and Ben Spence, through social media auditions.

“The guys who responded sent in a scene of their choice, a clip of them surfing, a story,” he explained. “It was kind of cute: most of their clips were shot by their sisters and mothers. They were so green when we started–but we created an on set environment where they could grow and develop.” The team knew all too well: green or not, an actor’s performance can be just as unpredictable as the weather.

"Even when you have a real problem: don’t panic and shrivel up into a corner. Use it to your advantage."

“It helped that I’ve been an actor,” Baker added. “And that Rick has a drama background. There are a lot of great guys who shoot water stuff, but they’re only water guys. They say ‘You lot stay over there, while we sort out the camera.’ That’s why those films never feel integrated.” He grinned. “And as for our kids, now they’re bloody good actors. They carry the film.”

By the time Baker’s team reached production, they had their template down. No need for further deliberation. But even then, they stayed flexible.

“No matter how well you’ve prepared,” Baker warned, “things will still go wrong. So you have to be open-minded. You have to let things evolve, keep looking for ways to make things better. Even when you have a real problem: don’t panic and shrivel up into a corner. Use it to your advantage.” Baker’s energy built like a wave. “And all those visual references, all those tools you spent so much time on: don’t get too married to your choices. They’re just a starting point. You grow from there.”

Thinking back on the 36 days they spent shooting Breath, Baker shared “We were out there, each of us surfing, sometimes two kilometers off the coast, and it was awesome and horrifying. It was chaos, I still can’t believe we pulled it off. I got my boat licenses during pre-pro, then after ten days of shooting, I was out there in the surf with a Mercury outboard from the ‘90s. We sunk it.” They all laughed.

Rifici had his own version of the story. “We tried using a Jetski–a water dolly, we called it. Got one take, but then the boat got clipped by a 15-foot wave. Clipped out the boat, then that was it. Lunchtime. One take, one amazing wave.”

They all laughed again–but then Baker got serious. “It’s what I learned from Ang Lee: when you’re on set, you’re just grocery shopping. The film gets made in the edit.” Baker gestured at Rifici. “Because he shot on 5K, most of it at 40 fps, we had flexibility in post. We could blow frames up, reposition the camera. And change the speeds.”

Let Your Film Breathe

The main key to their collaboration? They didn’t suffocate each other. They let their film breathe.

Baker tried to summarize. “Right from the get-go,” he explained, “we tried to remove all the artifice, to let the space exist as it was. Very few camera moves, almost no dolly. We tried to trust the frame, and the kids moving in it.”

“It wasn’t easy,” he admitted. “But throughout the whole shoot, we had this amazing sense of freedom. And not just in the water. Sometimes the rigor of filmmaking, the ‘OK, quiet please, take two, marking’ is important organizational business. But when you have two first-time kids, you want to help them develop, feel comfortable. You have to make all that secondary, it limits their freedom. The most important stuff we got was between ‘Action’ and ‘Cut.’ That’s what made this film what it is. We let those kids be kids, we gave them room to breathe, so they were like ‘This is fun.’ That was essential.”

Rifici chimed in with a last word. “Basically, we let each other be ourselves,” he attested. “We complimented each other in a dynamic way. It was never just a ‘Whaddya think Marden?’ situation. Or a ‘That OK with you, Simon?’ We simply jumped into it together, and it never felt like stepping on each other’s toes. We were all mucking in there together.”