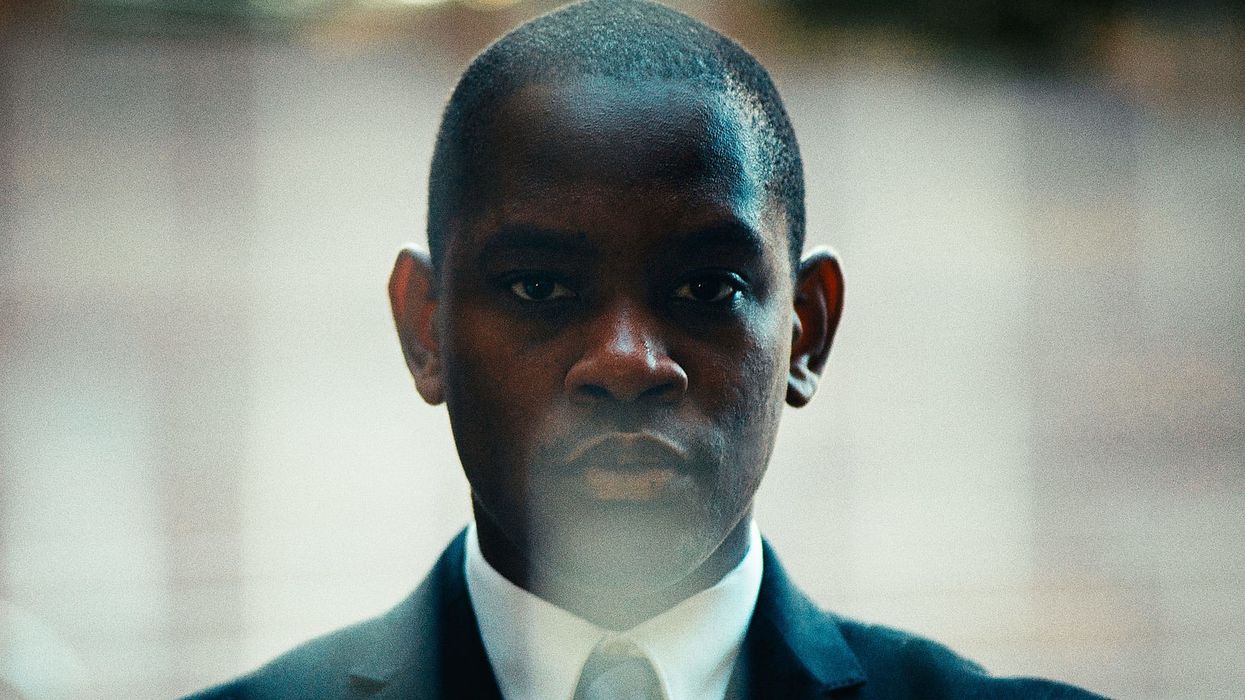

'You Have to Understand the Core of Narrative': Anthony Onah on 'The Price'

'The Price,' directed by Anthony Onah, is the story of the pitfalls of the American dream.

As many of its citizens are well aware, all American dreams are not created equal. For Seyi Ogunde (Aml Ameen), the 24-year-old first-generation Nigerian immigrant who is the protagonist of Anthony Onah's The Price, achieving the dream is an uphill battle that may cost him everything.

From an outsider's perspective, Ogunde, to whom Onah lent much DNA, is an immigrant success story: He went to Harvard. He works at a high-profile financial institution. He has an American girlfriend (Lucy Griffiths). But what lurks beneath the surface is a violent fracturing of two identities and worlds. Ogunde belongs to neither America nor the Nigerian immigrant community his family is so firmly rooted in, and reminders of this reality follow him everywhere, threatening to undo his sense of self. Backed into a corner, he makes a Faustian bargain. Of course, there is a price.

Following its premiere at SXSW 2017, No Film School sat down with Onah,Ameen, and Griffiths to discuss how a short film written as a form of catharsis turned into a feature, the relative merits of perfectionism to creativity, and why directors can't expect to please everyone.

"I see my career as two-fold, like Soderbergh: one for me, one for them."

No Film School: I have to say that I was incredibly moved by this film.

Anthony Onah: Thank you! I went to the bathroom before the Q&A and some woman ran up to me and kissed me and was crying. I'm a little shocked by how much of a moving experience it was for everyone. I mean, I sort of thought that would be the case, but I didn't fully imagine what it would actually be like.

Lucy Griffiths: I was moved, and I knew what was going to happen.

NFS: So, how did The Price evolve from a short into this feature?

Anthony Onah: Well, I lost my father. I was home for Christmas, and I was talking to my mom and we were going through some of my dad's stuff, and she said some things that moved me to tears. I [realized] I just really needed to understand my relationship with him and her relationship with him. I had all these feelings and thoughts and I didn't know how to process them. So I very quickly wrote a short [film].

Onah: The short had some success. It won a DGA award. I went to the Berlin Talent Campus at the Berlin Film Festival in 2012, and when I was there, I went through this feature writing workshop. I discussed the ideas, things I wanted to explore. We were talking about the story and how it relates to me, personally, and I was really encouraged to pursue it [further]. That was February 2012.

I came back to the States had a draft by May 2012. It was weak. I just sort of got it all out there. I started writing and re-writing, and I got producers on board: Justin Begnaud first, then Kishori Rajan. They would give me input. And it kept on developing. At a certain point, [the screenplay] starting getting into labs. We got into a lab at IFP, the Independent Filmmaker Project, and we got into the producing lab and directing lab at Film Independent. Through their terrific catalyst program, we got partnered up with a lot of the financial partners and equity donors that provided the capital that made the film come to life.

"You have to understand what is at the core of narrative and why we sit around the campfire to tell stories. It may seem large and abstract, but it's at the core of what we do."

NFS: What did you learn about the writing process going through the labs? I'm sure you changed the script a lot.

Onah: Yeah, yeah. Going through the various different labs, I [learned] that you have to focus on story and character. Those are the things that will hold the audience and move people. It's easy, especially for first-time filmmakers, to get caught up in other things in the process, like to get carried away with the camera.

I also learned about being in touch with my interior emotional life and finding the collaborators to help bring it to life.

NFS: You went to film school at UCLA. How did your education compare to making your first feature?

Onah: I had a great experience at the UCLA film school and a set of wonderful mentors who got me thinking about what was important in narrative. The basics were great because my background was very different; I was in science before I transitioned to film. So that first year was a crash-course for me: set operation, loading cameras, lighting, F-stops, things I didn't know anything about. It was great to learn all of that stuff, but I'd say what I really took away that I had to build upon on this movie is what mattered in story. It's these basic questions: "Who am I? Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going?"

You have to understand what is at the core of narrative and why we sit around the campfire to tell stories. It may seem sort of large and abstract, but it's at the core of what we do. Keeping this in mind allows me to really know I'm onto something versus just, you know, writing bullshit, which is very easy. There's a lot of that in film school.

"That core confidence—that sense of knowing who you are and what you want—is essential. This isn't just unique to film; this is all of life."

NFS: Aml, what about the story and script really compelled you and got you excited? I know that you hunted Anthony down and said, ;"I want to be in this movie."

Aml Ameen: Well, a lot of men relate to the difficulties between fathers and sons. There's a time in your life where you stop agreeing with some of the things your dad is saying, and sometimes you end up in combative situations with your father. I remember that time in my life. My parents got divorced when I was like 15, and I spent a lot of time not liking [my father]. For years, we were in combat, and I just didn't understand why. I put pressure on my parents to be perfect, and when they fall from that grace, as we all will, it's really hard. I think that part is so universal. So that, along with the love story, is one of the core fibers of the film.

Then you know, for a young black actor...I can't think of an example where you could play such a multifaceted character at 24. Anthony really made this character human and reflected how people actually are. So I think that was a beautiful thing to give voice to.

Onah: To piggyback off of that, when [Aml and I] first met, one of the things that he said really struck me. It made me go, "This is the guy." He said, "Thank you so much for writing this character as a human being." I was like, "Yes! You got what this was supposed to be!" We need to sort of capture this journey of this human being. That was critical in my making the decision to [cast Aml].

NFS:Seyi demonstrates how contradictory human beings can be. We disappoint ourselves and each other. He's also a perfectionist. Anthony, I'm sure that element lives in you, as the creator. How do you deal with that pressure?

Onah: Well, it's a good way of motivating myself. I was a producer on the film as well, I [wanted to] push this as far as it can possibly go in service of the story. But even in production, I had the understanding that every decision is made through this prism of story and character—what serves the telling of the story. So while the perfectionism was there, I think I was able to reign it in when it felt like it might be too destructive or deter from bringing the story to life.

"Until you reach your limits, I think it's great to be a perfectionist."

Griffiths: I think perfectionism gets a really bad rap when it comes to performing. We've both danced in the past, and you rehearse again and again and again until it's perfect. Otherwise, why would you put it out? [People think] perfectionism means you are a bit neurotic, stressed out, or somehow obsessive or unrealistic, but I think it's [about] coding a standard, and practicing as much as you can within the parameters that you've got to work within. At some point, you say, "Okay, I accept that we don't have any more time to do this, even though if we did, I'd want to do X." Until you reach your limits, I think it's great to be a perfectionist.

Onah: I'm a big fan of David Fincher, and he's famous for millions and millions of takes. That's his rationale—he wants to get to the point where you feel like you've sat in that chair a thousand times because your character would have sat in that chair a thousand times in his apartment. And then you're really coming to a place where it's instinctual.

I think that we were all on the same page about leaving no stone unturned, and understanding that this was about a journey to find the truth. But there are limits, and we just started moving on when we hit those limits.

NFS: Anthony, what surprised you about being a director form a creative standpoint? And from a producer standpoint?

Griffiths: Did you have any expectations?

Onah: I guess the challenge was sort of understanding my role as a leader on the set—understanding the things that you have to do as a leader may not always be the most popular things. I think I voiced this to [Lucy] when we were sitting in the van before the sex scene. I said that you have to choose the things that are best for the film. It will not always make you the most popular person. My job is to be in service of the film.

Griffiths: Your incentive can't be to be liked.

"When it comes to understanding how people work, the best starting point is yourself."

Onah: Yeah. And on the producing side, I just didn't have enough money. I think that's a universal [sentiment]—there's never enough money, never enough time. You just have to make the decisions with the resources you have that best serve the film. It doesn't matter if you have a $2 million budget, or a $20 million budget, or a $200 million budget.

NFS: If you were to give yourself advice before everything came together, and you knew you were going to make the film, what would you say?

Onah: You have to believe in yourself, I know it might sound cliché, but you have to believe in yourself. If you don't believe in yourself, no one else does. That was something I had to go through as well—to reach a point where I could walk into a room and say, "This is what I intended to do. Are you on board or are you not on board?" That core confidence— that sense of knowing who you are and what you want—is essential. This isn't just unique to film; this is all of life.

NFS: I can imagine it was a little bit scary to give a partial portrait of yourself to the world. Do you think that you want to continue making films like that?

Onah: Yeah. Absolutely. But I'm very excited about making larger films within the Hollywood apparatus. I'm a huge fan of crime films. I'd love to make a modern-day crime film in the tradition of the Roaring Twenties. I'm also a huge fan of sci-fi. I definitely want to do that, but also to tell smaller, more personal and idiosyncratic stories that draw on my background as a Nigerian-American, and that draw on my background in science. I hope I can sort of migrate [these stories] to the Hollywood apparatus and use that machine to reach a wider audience. So I see my career as two-fold, like Soderbergh: one for me, one for them.

NFS: I can imagine there's a kind of catharsis that comes with the act of sharing personal stories.

Onah: I could not have anticipated what I would learn about myself in this process—about who I was, who I want to be, what really mattered. Putting myself under the microscope, understanding the constituent elements of myself, and extending that to understanding the constituent elements of people...it fosters empathetic engagement. One of the hardest things in life is really just understanding how people work. When it comes to understanding how people work, the best starting point is yourself.

And, you know, I didn't sit down and say [making this film] was going to be therapy, I didn't sit down and say this was going to be a vehicle for my personal growth. I just wrote about things that I wanted to understand. This is a highly fictionalized story, but the essence is my experience. And if you're looking at it truthfully, you can't help but see who you are.

NFS: Is there anything else any of you would like to add?

Griffith: In real life, we're generic assholes.

Onah: We don't need to go into real life. There was enough real life on the screen.