Watch: The Style of 'Requiem For A Dream' Makes Addiction All Too Relatable

Darren Aronofsky's 'Requiem for a Dream' is a one-of-a-kind film. Here's how it functions as an out-of-control ride into the abyss.

A requiem is, loosely, an act of remembrance for something departed. Requiem for a Dream, the second feature directed by Darren Aronofsky, is an adaptation of Hubert Selby, Jr.'s novel about the downward spiral of four characters battling addiction.

Though the film is narratively structured in three parts (summer, fall, and winter), Lewis Criswell's video essay, The Structure of Self-Destruction, maintains that the "core ideas are manifested by its violence acceleration of intensity." The structure of the film is linked to its editing, camera, and sound design, all working together to weave an interconnected tale of four connected characters. And then, one by one, it leaves each of them alone.

Your style is your message

According to Aronofsky, "we didn't want, in any way, to be accused of being an MTV movie, because those videos and those commercials are basically style without substance....[In the film] you have this theme which is your mantra...with every single camera technique we use, we tried to face the truth." The film's use of camera and editing is relentlessly subjective, which is part of the reason it's so difficult to watch.

Requiem's style so amped up that it actually becomes a far more "realistic" film as a result.

Unlike most films that have a pretense of "objectivity" posing as realism, Requiem's stylization is so amped up that it actually becomes a far more "realistic" film as a result. The technique captures the experience of addiction by finding its cinematic objective correlative. The use of the fast montage is, perhaps, the best example: the characters spend so much in the search for relief from addiction that when they finally get it, "the effect of montage makes it pass so quickly that there's no time to enjoy any of the temporary enjoyment." This, in turn, distorts their perceptions, driving the editing and camera work.

Develop a relentless subjectivity

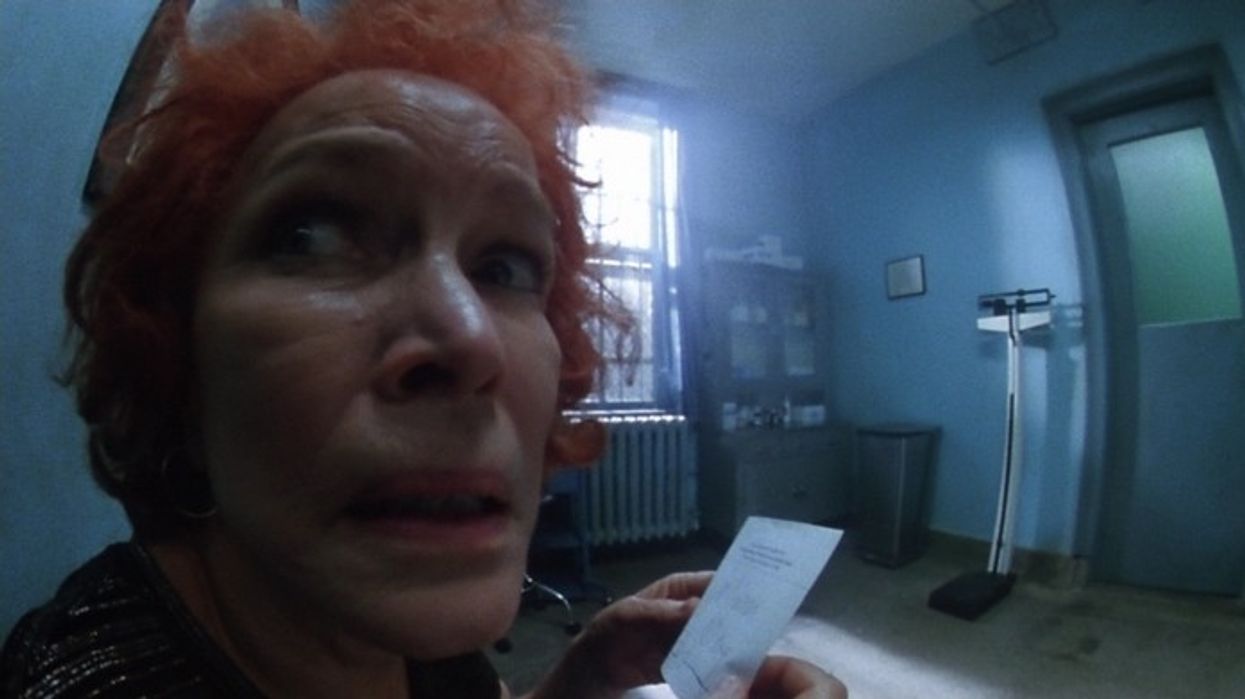

While the film makes use of multiple distortion techniques to hammer home subjectivity, what unites each of the characters is the director's use of the Snorricam, the body mount camera system used in Aronofsky's first film, Pi, and in RFAD as a unifying aesthetic. Unlike some films from the early 2000s that overused/abused camera tricks like the "bullet time" effect—used so effectively in The Matrix—here the rig's style is not used because it looks "cool," but because it is used to help the tell the story.

They're avatars in a first-person video game no one wants to play.

Requiem takes advantage of the rig's inherent strengths: scenes are framed so that ultra wide-angle shots move the characters through various circles of hell in real time. They're avatars in a first-person video game no one wants to play. Meanwhile, the same wide-angle shots emphasize movement, capturing internal states as the characters move through space, either lurching, running, strung out, or tense. And because the camera is attached to the actors, we cannot look (nor get) away from them, in much the same way as they cannot get away from themselves.

It's a 100-minute crescendo

According to Criswell, "Aronofsky crafted his sophomore piece with more inclination towards musical structure rather than taking inspiration from conventional cinema." The film builds inescapably towards its crescendo and subsequent collapse. As it moves toward its finale, the editing/cutting from sequence-to-sequence grows faster, and the film itself begins to resemble one of the previous drug-use montages.

In Requiem for a Dream, "what begins as a filmic style becomes the foundation of the movie's message," and this, along with terrific acting and expert execution—and an aesthetic sense that informs that execution—is what makes it one of the most powerful classics of the 2000s. It's not underseen for lack of quality or influence: it had salubrious effects on the careers of all involved and is routinely cited as one of the best films of the millennium.

The rush for faster (and more convenient) means of everything are uncomfortably close to the character's rush for impossible dreams.

I love this movie, and yet I haven't sat through it as nearly as many times as I have my other favorites. It drains and exhausts, and the feeling of relief at the end is matched by profound sadness and a discomforting recognition.

The addictions depicted in this film might be extreme and thus easy to dismiss as cautionary tales, but the viewer relates because it reflects our own society. The rush for faster (and more convenient) means of everything are uncomfortably close to the character's rush for impossible dreams.

Source: Channel Criswell