Watch: Take a Crash Course in Motion Picture Film Gauge

Let's give 16mm, 35mm, and 65mm its proper due.

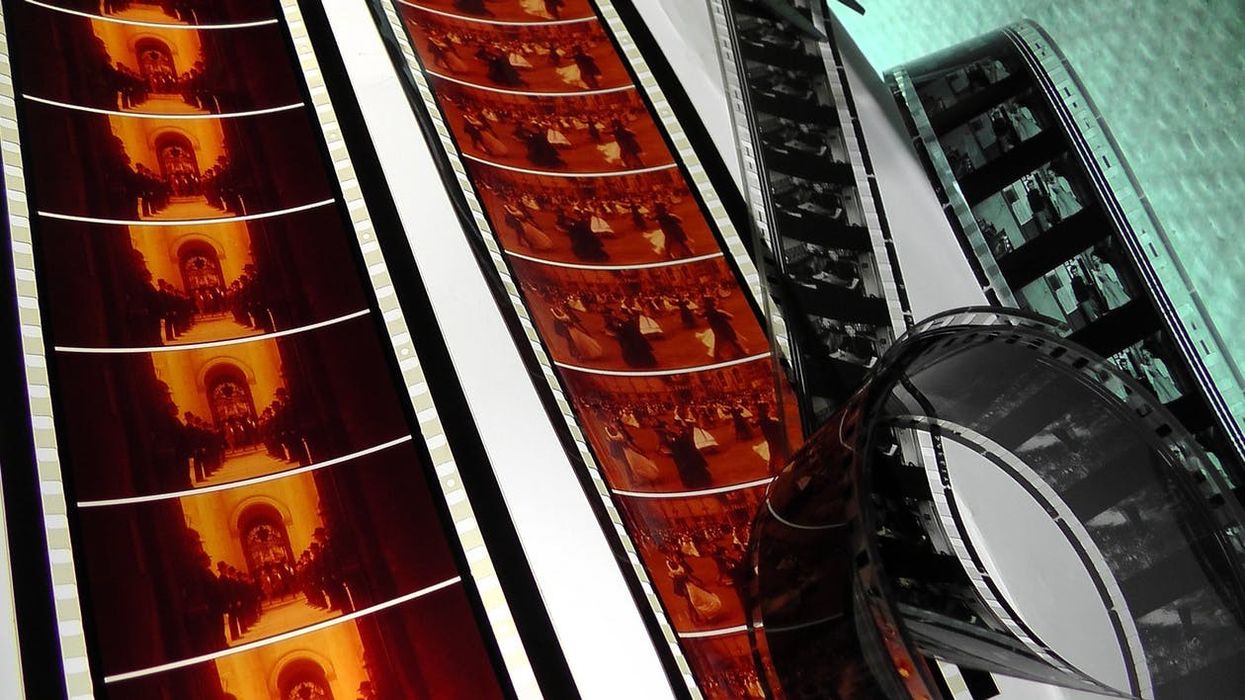

When we discuss film gauge, we're specifically speaking about the width of the frame itself, that is, the available space that is exposed to light when run through a movie camera, measured in millimeters. As Jacob T. Swinney says in his video on Fandor, film gauge "heavily affects the look...mood and tone" of a movie.

Below, Swinney looks at three film gauges: two that you've probably run across (or are at least familiar with) and one that's comparatively rarer, but which you've probably seen at the movie theater at least once.

16mm

16mm (and Super 16) are indie favorites, having been the film stock of choice for a huge number of films, including Pi, Clerks, The Hurt Locker, and Junebug. Because it has much less exposure area than the more common 35mm, 16mm provides a grainier look and has a "somewhat dirty texture." It has a gritty feel, due mostly to the larger grain, a physical property of the film being developed, although there are digital plug-ins that can emulate this look.

While many indie filmmakers have traditionally made use of 16mm due to it being a cheaper alternative to 35mm, TV shows such asThe Walking Dead are shot on 16mm before being transferred to digital.

Swinney notes that the "grainy" quality apparent in 16mm can also provide feelings of "warmth and nostalgia," mentioning films like Moonrise Kingdom and Carol, both of which were shot on 16mm, and neither of which have super gritty aesthetics. "16mm has a lot of personality simply because it's easy to distinguish as actual film," says Swinney, and, while it's possible "to confuse 35mm with digital...16mm always possesses an obvious and unique look."

35mm

35mm is the industry standard. Compared to 16mm, it's more than twice as wide and, with a far greater area of film that can be exposed, there's less grain and a "denser, deeper look." 35mm can really do anything, it can handle any genre, and with today's film stocks that take an exposure in very low light, there's almost nothing that a good DP can't get out of 35mm.

65mm

Much larger (and more expensive) is 65mm, also known as 70mm, with the former number being the size of film that goes through the camera and the latter the size that actually gets projected. When you think 65mm, think epic, from big Hollywood musicals like Oklahoma!, to Lawrence of Arabia, and, of course, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Basically, "it's the best looking when it comes to all around picture quality."

Paul Thomas Anderson used it on The Master because he thought the format evoked the 1950s, and there's not much that beats the epic frames you can compose with 65mm/70mm. Never one to be outdone, Christopher Nolan shot Dunkirk in both 65mm and its cousin, 65mm IMAX, and the film was released in several formats, including 35mm and even digital.

In 2018, people are still trying to get that film look, even if it means using a bit of digital trickery to get there. The reasons for this are as endless as aesthetic preferences and references, but there's also something to be said, both as a moviemaker and a moviegoer, for having a physical object in the film, a tactile "thing" that has had an image etched with light.

In an age of infinite recursion and endless, perfect duplication, the filmed object still gives off an analog buzz, and for all of its added expense and difficulty, that's one reason many movie makers are in no hurry to put film, in its various sizes, away for good.

Source: Fandor