Inside the Oscars Live-Action Shorts: 'Don't Let the Buzz Kill Your Independence'

Three Oscar-nominated shorts directors reveal the challenges they faced in production and more.

Last year, the Oscar-nominated live-action shorts had a clear thematic throughline: coming-of-age stories. When I spoke to the directors, they told me that the nominations had opened the door to Hollywood.

This year, I spoke to three Oscar-nominated shorts directors: Marshall Curry (The Neighbor's Window), Bryan Buckley (Saria), and Meryam Joobeur (Brotherhood). Two of them already had open doors in Hollywood—Curry is an accomplished documentarian, and Buckley has directed 65 Super Bowl commercials. (Read our recent interview with Buckley, in which he parcels out some tough-love filmmaking advice.)

Joobeur, meanwhile, is an up-and-coming director who isn't necessarily interested in exploiting the chance to make the next big blockbuster; she'd rather pursue independent projects that allow her the freedom of creativity and process that she had on Brotherhood.

The shorts themselves are riveting. In The Neighbor's Window (which you can watch below), a married couple turns into a pair of voyeurs as they observe the younger couple that just moved in next door. At first, it seems as if this newfound hobby will have dire consequences for the married couple's relationship, but in the end, a surprising turn of events affords them some welcome perspective.

Saria is a fictionalized account of a real-life tragedy in which dozens of young Guatemalan girls burned to death in an orphanage. Buckley brings an intimate, emotional dimension to a shocking injustice. Brotherhood begins as two brothers return to rural Tunisia from a stint as jihad fighters in Syria. Their family, who doesn't agree with their actions, struggles to accept them, and some misunderstandings have devastating consequences. That film, lensed by Vincent Gonneville, boasts some of the most exquisite cinematography I've ever seen in a short; the 4:3 aspect ratio and attention to atmospheric detail, places the audience in the turbulent inner lives of these characters.

No Film School caught up with the directors the week before the Oscars to discuss the challenges they faced making their films, how they executed their visions, what they learned from it all.

"We made the call that we were going to forgo all festivals and just go for the Oscars. I think we might be one of the first films to ever do that!" —Bryan Buckley

NFS: What inspired this short film?

Marshall Curry: Years ago, I heard a story on a podcast called Love and Radio that really touched me. A woman named Diane Wiepert described having a young couple move in across the street from her and she develops this sort of Rear Window obsession with watching them. The story that she told just kind of stayed in my mind and in my heart. A few years later, I was trying to think of a good fiction film for my first narrative project, and that idea popped into my head as the seed for a short film script.

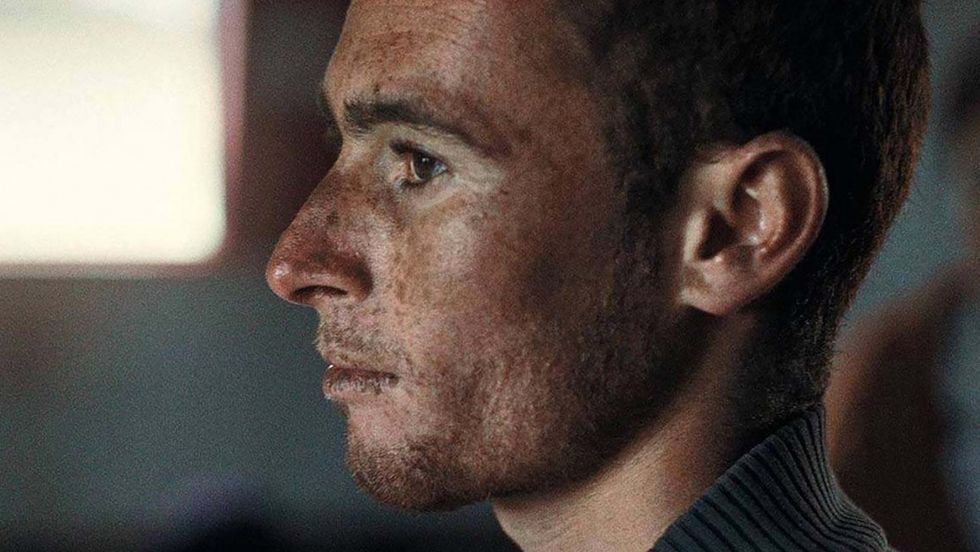

Meryem Joobeur: I felt like I wanted to discover my country a bit more. I had never been to the north of Tunisia. And so my cinematographer Vincent Gonneville and I went on a two-week road trip. One day, we saw Malek and Chaker [the film's two lead actors] walking on the side of the road. I made eye contact with Malek and I told Vinny, "Stop the car. We need to take their photo." But when we asked to take their photo, they said no. They were very shy and suspicious. So we drove away.

Joobeur: But Vinny and I were really excited. There was something really special about these boys and the landscape. And as we continued on our trip, we discovered that in the North there's the town, close to where we saw the boys, where a lot of men have gone to Syria—higher than the average percentage for our country. I knew that as a society we were struggling with this issue. So over the next year and a half, I was thinking about the boys, thinking about this fact, and the story just naturally came about. I remember I wrote it in a day. And in summer 2017, I asked Vincent, "What do you think about going looking for those boys?"

We didn't have their names and we forgot where we found them. So we just drove to an approximate location and started asking strangers, "Do you know two redheaded brothers with sheep?" It led to many misadventures because it's such a random thing to do. But thankfully, just as we were giving up, we took a back road, and Vincent recognized a pile of rocks from the place where we found them. A shepherd was there and he pointed out their house.

"I was nervous because this was actually a really crazy situation... But I followed my instincts, and I was right." —Meryem Joobeur

Chaker and Malek came out of the house. They were really suspicious. They didn't recognize us. And at that moment, I was nervous because this was actually a really crazy situation. But I told him, listen, we met a year and a half ago, and I wrote a script for you. I want you to act in it. At first, they were like, "No." But then I joked with them about how long I've been searching for them and how crazy it had been. And they started laughing, and then they opened up. I told them I'd be back in six months. I followed my instincts about them and I was right.

Bryan Buckley: Well, I was sitting where I am right now, which is in my office, and my phone went off with a news alert. It said, "A Locked Door, a Fire, and 41 Girls Killed as Police Stood By." I obsessed over [the story] for a week, researching it. I wrote the script after that.

NFS: How did you get your short off the ground, both in terms of financing it and the logistics of pre-production?

Curry: I wrote the script and got a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts. It was a small grant, but it was enough to offset some of the costs. The rest of the money I just paid out of my pocket, actually. We made it for a micro-budget with everybody working somewhere between free and 5 or 10% of their normal commercial rates. We got actors and crew who all just liked the script and decided that it would be fun to make.

Then, I started seeing if I could pull together crew. My first recruit was the DP, Wolfgang Held, who I had worked with on some documentaries, but he also shoots fiction. He's part of a film collective that owns a bunch of really nice high-end gear with some other DPs. And so we were able to access their gear for a steep discount. Maria Dizzia agreed to play the lead, and once I had the two of them, that that helped open the doors to the rest of the crew.

Joobeur: We knew that we wanted to keep it a very small, intimate project. I got funding from the Doha Film Institute, which is a film fund based in Qatar that helps directors in the region. I live in Montreal, so I was also able to access another fund called the Quebec Arts Council, which is aimed at funding independent artists. We also got a bit of money from a film festival in Sweden called the Malmo Arab Film Festival. And we just built the film with this tight budget.

Buckley: I have a production company, so I financed it myself. I just said, "We're going to go do this and we'll work around whatever jobs I have."

When you're doing a film that's designed to make no money, you have to figure out how to mitigate your losses while creating what needs to be created to tell that story. And the thing about this short is that it's fairly epic in scale. I wanted to tell the story accurately, as best I could, based on all the reports that I had. I wanted people to experience what the girls experienced. And that meant recreating the facility, both the interior and exterior, identically.

"When you're doing a film that's designed to make no money, you have to figure out how to mitigate your losses while creating what needs to be created to tell that story." —Bryan Buckley

Production-wise, it just didn't make sense to shoot in Guatemala given the political nature of what we were doing. We could run into some problems, in theory, with the government. I didn't want us to get into that mess. But we originally scouted in Guatemala. We went to the facility where the fire happened and shot pictures of it and got all the specs. We knew we were never going to find that same kind of exterior in Mexico City, but I felt like that exterior was really, really important for the telling of the story.

We found an abandoned hospital in the downtown area, which we used for the interior. And then, for the exterior, we just found a tree in the mountains, and then found an area in the city where the trees matched. And then we built a wall to match the exterior of the facility. It was a pretty big undertaking.

NFS: Tell me about the process of production. What challenges did you face?

Curry: We shot for four days. Most of the film takes place in an apartment, although one of the big logistical challenges was that we needed a second apartment that would into the primary apartment. We didn't want to fake that—we wanted there to be shots that made it clear that the apartment really did have a sightline into the neighbor's window. And so that was a big challenge was finding those apartments. As it turned out, we shot it in my building, in a very generous friends' apartment. And then I introduced myself to the neighbors across the street and they generously allowed us to shoot in their apartment for one day.

We had maybe 25 people working on the film, which is quite small for a fiction film, but pretty big for documentary crews, which is what I'm used to.

Joobeur: On set, we had six actors. Then we hired a local fisherman and farmer to be our PAs. The team was 12 people, plus the actors. It was pretty tight, a seven-day shoot.

I didn't do very intensive acting workshops. I had an assistant director from Tunisia, and we did little techniques to get the boys used to the presence of the camera and somebody directing them. I think the biggest thing I learned from that experience—and this is true for actors with more experience—is that as a director, your biggest strength working with actors is creating an environment of trust and building confidence.

I just spent a lot of time with them, getting to know them, getting to know their lives. They needed to connect with me on a more emotional level. And once that was established, they trusted me. So when it came time to directing them, I didn't have to do any crazy techniques or anything. It was really very minute detail work. They had the gift and I just needed to help them channel it.

"As a director, your biggest strength working with actors is creating an environment of trust and building confidence." —Meryam Joobeur

Buckley: With the complexity of the roles, I thought it was highly unlikely that 12 or 14-year-old actors would be able to reach the depths of character and the survival instinct that would be necessary to convey in the film. I thought that if we worked with an orphanage, we could possibly do two things: one, we could find kids that have that street toughness to them. And two, we could show [the audience] that these are the same kids as the safe house in Guatemala where the fire happened. In the news, you can't really envision, "Who are the girls that died?" You never get to know them.

We found an orphanage and talked to the girls, and they said they didn't want this kind of tragedy to happen again to their fellow orphans or kids who are in difficult positions. So, they all jumped in to do the film. Every single kid in that orphanage.

Buckley: There was a two-month training period to sort out who was going to be the lead. For Gabriela [Ramirez, who plays Ximena]'s first audition, all the other girls were giggling and running around, and then Gabriela shows up and literally knows every line of everything. I work with a lot of real people, and I have to say she was the best "real person" audition I've ever seen. I was just blown away. I was like, "Oh my God, this girl." Ultimately, Estefania [Tellez, who plays Saria] and Gabriela rose to the top. We had an acting coach and we just rehearsed and rehearsed and rehearsed. They'd never been in front of a camera.

NFS: What was your vision for the cinematography? How did you collaborate with your DP?

Curry: I really wanted the film to feel natural. I care about things feeling real. And so I didn't want there to be any shots that drew attention to the cinematography. I mostly wanted everything to be in the service of the story and the emotions of the characters.

The movie doesn't have a fake documentary style—it's not shaky camera or anything like that. I wanted it to be beautiful and it took a ton of work from Wolfgang to make things feel both beautiful and cinematic, but at the same time, naturalistic and authentic.

"The main inspiration for the cinematography was portrait photography. We used a 4:3 aspect ratio to focus on the characers' faces to communicate what was unsaid." —Meryam Joobeur

Joobeur: Vincent [the DP] has been my collaborator since film school, so we have a history together. Initially, when we were talking about the film, Vinnie was proposing that we do more elaborate setups. But I always had this instinct that I wanted to simplify. We did some tests right before the shoot and then arrived at the decision that the main inspiration for the cinematography would be portrait photography. We also decided we were going to try to make it as easy as possible for the actors, so we didn't use any lights. It was almost all handheld camera work. We focused on their faces. There's a lot of silent tension in the film, so I was drawn to the faces because they could communicate so much of what was unsaid in the film.

Joobeur: We shot on the ALEXA Mini with Sigma lenses. I had never done any projects with a 4:3 aspect ratio. I was at first a little bit nervous, but we did some tests and I really liked it. It went into the philosophy of portrait photography and really helped focus on the faces of the characters. And in the end, I think, with the editing, it adds a bit of that claustrophobic feel. You can't really escape the inner worlds of the characters. So it was up being a very instinctive choice that translated narratively.

Buckley: Our DP, Galo Olivares, worked on Roma as a "cinematic collaborator" with Alfonso Cuarón. Galo is an unbelievable cinematographer.

The mood of Saria is very painterly. It was designed to give you the feeling that you really were in that world, painting with light. It needed to be real, but keeping the cinematic feeling.

We didn't have a lot of lighting. Every shot was composed and thought out. I did all the boards. I did every frame of that thing just to make sure the details were right. We discovered some stuff on set, but there was no room for error with a five-day shoot. We had to be dialed in.

"When you choose to work with challenges instead of trying to fight them, it can actually lead to creative spontaneity and gifts."

NFS: What challenges did you face making this short?

Curry: Well, it was my first narrative film. But the grammar of making a movie is the same, whether it's nonfiction or fiction. It's wide shots and close-ups and reaction shots and tracking shots and editing. The way that shots are put together is very similar, whether it's fiction or nonfiction, but the process of getting those shots is quite different. For me, shooting scenes out of order was a big learning experience. It was a challenge to track the emotional arc of a scene when you shoot half the scene one day and the other half the other day.

Curry: I think that working with actors was a lot like working with real people. When you're shooting a documentary, you try to put people at ease and make them comfortable with who they are so that they can relax and be natural and reveal things about their lives and emotions. And with a fiction film, once you've talked with the actors about their characters and once they understand the emotional goals of each scene, you're doing the same thing. You're trying to create a set where those characters' feelings can come out in ways that feel natural and organic.

Joobeur: A lot of people in my life didn't even know I was making this film. It was almost like my secret. I didn't intentionally hide it from anyone. It's just that I wanted to do something intimate. The process was the purest, most important thing for me.

Before, when I shot films, I was overthinking everything. I put a lot of pressure on myself. Am I doing the right thing? Will people like the film? It was becoming toxic. So I let go of all those things with Brotherhood. The moment I let go and had faith in following my instinct, everything fell into place.

"The moment I let go and had faith in following my instinct, everything fell into place." —Meryam Joobeur

Even the challenges had a really important narrative effect. The weather was storming, which was hard for our small team. But the stormy sounds added to the tension. So every challenge I had, I chose to work with because it added to the film. Looking back, I'm not like, "Oh my god, this was so hard." It's more, "Thank god I learned so much on this thing."

When you choose to work with challenges instead of trying to fight them, it can actually lead to creative spontaneity and gifts. Brotherhood is definitely a testament to that. I learned what the conditions are that I need for my creative voice. I am a very intuitive person.

Curry: Well, that remains to be seen, to be honest. But I'm having a bunch of meetings with folks. I don't have a new project that's greenlit. We'll see what happens. But it definitely has opened doors to conversations and meetings and the initial steps of getting a feature film off the ground.

I've been making films for a while, but all nonfiction. So for me, just the experience of making something fiction was really creatively satisfying, and hopefully, it'll be able to convince people with money and power that it's something that I can do.

Joobeur: I'm enjoying the Oscars in a very fun way with my family and my friends. It's such a crazy achievement—it's the first time a Tunisian film is nominated.

Brotherhood has really opened up a lot of opportunities, especially on the festival circuit, that I never envisioned an Arabic-language short opening up. I think it's allowed me to learn a lot more about the American industry.

For my next film, I made a clear decision that I want to stay in the grant system. The intimate approach, which I used for Brotherhood, is the best thing for the stories I want to tell. I had a lot of creative freedom working with producers that I know very well.

I'm just treading carefully and listening to my voice. Obviously, there's buzz around the Oscars, but I think it's important to not get sucked into it too much and stay on the path that is right for you. I think as a young director, sometimes we get really scared that it's now or nothing. It's like, "Oh, I need to make the most out of this Oscar situation, or the doors will close." I don't think that's the healthiest approach for me. I need to focus on what's right in my heart. I can't feel like this is the only moment I have to "succeed" because I think that can kill the creative voice.

Buckley: The Academy nomination is a massive spotlight. With Saria, we felt there was an urgency to getting the message out to the public. And there's no better place than the Oscars. So, in September, we made the call that we were going to forgo all these festivals and just go for the Oscars. I think we might be one of the first films to ever do that!

'Anora'Neon

'Anora'Neon Annie Johnson Kevin Scanlon

Annie Johnson Kevin Scanlon