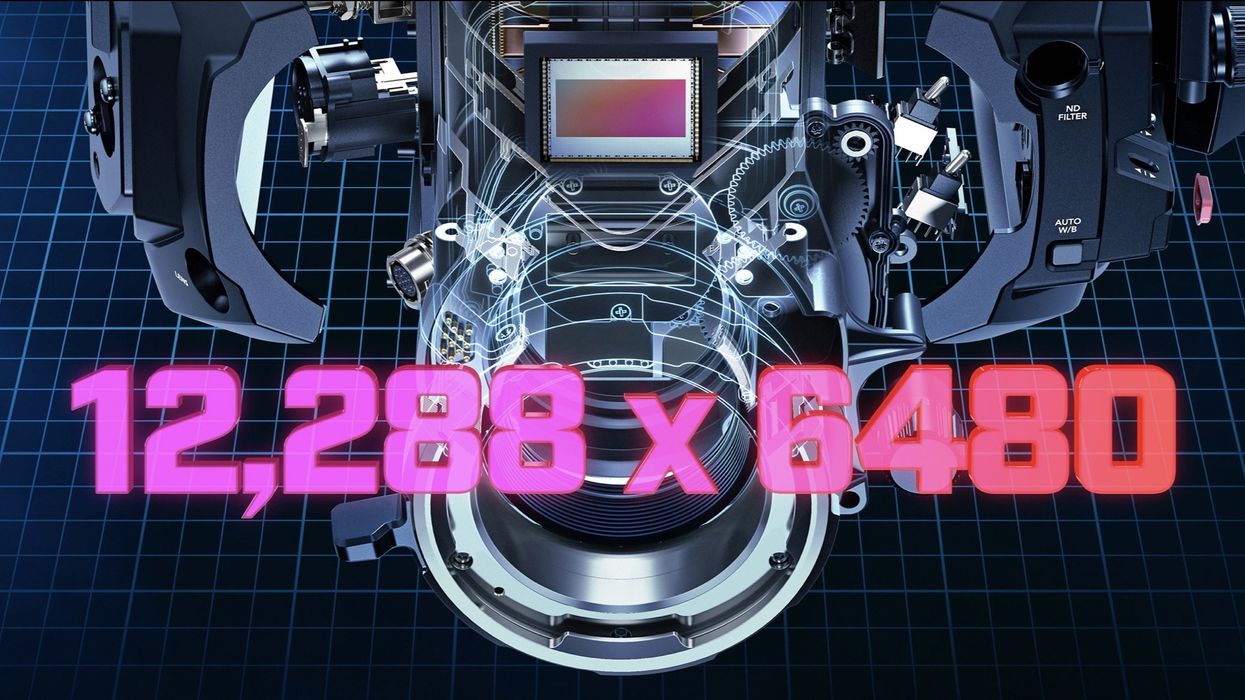

You've Got 12K—What Do You Do with It?

Modern cameras offer a lot of resolutions. Why are there so many choices, and what should you shoot for your project?

There are a whole host of resolutions filmmakers need to keep track of, and it's only going to keep growing.

With the newest camera from Blackmagic, the URSA Mini Pro 12K, you can shoot up to 12K files (that's files that are 12288 x 6480, or 79,626,240 pixels per frame), or work in 8K, 6K, or even 4K. With all of the options on the table, how do you decide what is the best format for your project, for both capture and delivery?

Let's dig into the differences between resolutions.

Aspect Ratio

The first decision you should make is what aspect ratio you want to capture your project in.

Aspect ratio refers to the ratio of the width of the image to the height, and in cinematic terms we usually write it as a ratio of the width x 1, so a square format would be 1x1 and a format that was twice as wide as it was tall would be 2x1.

In video terms you'll often see 4x3 or 16x9, but other than those two formats, it's usually reduced to the x1 equivalent, with 4x3 being roughly equivalent to 1.33x1 and 16x9 being roughly 1.77x1.

While the choice of aspect ratio used to be somewhat restrictive, with 1.33x1 dominating before World War II, and 1.85x1 and 2.39x1 dominating the second half of the 20th century, it's now a wide-open field for how you want your final project framed. While 1.33, 1.85, and 2.39 are still common, you'll see 1.66 (originally more common in Europe), 2x1 (created by Vittorio Storaro), and more. If you are finishing for television and streaming, 1.77x1 (full-frame 16x9, without any bars) is very common as well.

This is fundamentally a personal choice for every filmmaker, and one you can easily replicate both in-camera and in your final color grading process with the "blanking" settings in DaVinci Resolve.

There are a ton of arguments for all the formats, with some projects requiring more vertical height and preferring the more square formats, some needing widescreen, and many now considering shooting vertical (9x16) for platforms like Instagram and TikTok.

Keeping in mind that while it might be a personal decision for your project, your distribution platform might have opinions as well, and if you are already set up at a platform or aiming for a specific one, you should read their tech sheet to see what is allowable.

16x9

You'll notice we said above 16x9 is becoming very common for filmmakers delivering to the web, streamers, and television, but you might not have noticed it doesn't match any of the older formats like 1.85x1 or 1.66x1.

16x9 was actually deliberately created in 1984 by Dr. Kerns Powers as a format to support as many other formats as possible. By overlaying the layouts of 2.35x1 and 1.33x1, you get an area of roughly 1.77x1, which means that if you have a 16x9 final video format and put a 1.33 video in it (with pillarbox bars on the side) or a 2.35x1 video in it (with letterbox bars) you are using roughly the same area.

Some of you might be wondering, "Do I still need to make my video file into 16x9 even though I'm shooting in another format? If I'm shooting natively 2.35x1, why put it in a 16x9 box with all that extra wasted space?"

Generally, you still should create a 16x9 file, since 16x9 files are by far the most widely accepted video format today, and you'll run into the fewest issues. When delivering 4K, for the most part your safest bet is to deliver in 3840x2160, the standard UHD 16x9 format.

While big platforms like Netflix will take your 3840x1640 file (if you shot a wider aspect ratio like 2.35x1), you can really only depend on the big platforms to handle that file properly. Smaller platforms are notorious for doing strange things with those files, including stretching them to fit a 16x9 window without letterboxing.

Even worse, it might look fine in their web player but then look odd in their streaming system or mobile viewer. We've been to countless film festivals where films were shown in strange aspect ratios that didn't look correct, and while it doesn't happen at the top-tier fests, it definitely happens all the time in the lower-tier festivals.

So, whatever aspect ratio you shoot, you'll want to finish to some version of 16x9 to be as safe as possible with your deliveries, unless you are working only on a theatrical and high-end streamer release with no Blu-ray.

Digital Cinema Initiative (DCI)

DCI, short for Digital Cinema Initiative, refers to the group that set the standards for digital cinema. While the final specification came together in the early 2000s, one key aspect of the format is its preference for 2K and 4K files that are a little wider than 16x9 (2048x1080 instead of 1920x1080). This was really developed as part of Cineon, Kodak's digital imaging workflow, in the early 90s.

On most screens, there is not a dramatic difference between files mastered in "HD" and "2K" or "UHD" and "4K DCI" formats. We're talking about 240 extra pixels of horizontal resolution and the same vertical resolution. It's very, very, very minor, even in 4K, which was far into the future at that point.

In 2K it's 128 pixels extra, or 64 pixels per side. In fact, many at the time thought Kodak had largely created the 2K standard just so that their Cineon workflow would be more than just "normal HD" for marketing purposes, since the extra 128 pixels of horizontal resolution just isn't that big a difference.

The bigger benefits of Cineon over HD were in things like color space and bit depth, which are wonderful but don't have the marketing buzz of a larger resolution.

For whatever reason it was created, we are stuck with it now. Theaters have full DCI resolution projectors, but basically no one else does. We recommend working in DCI only if you are shooting a project that is 100% guaranteed to get a wide theatrical release, like a new action movie franchise.

If you are looking at theatrical as only a small part of your release, if at all, it doesn't make sense to work in a DCI format. You are better off sticking with the typical 16x9 ratios for your master file. There is a little-known secret that the DCP (digital cinema package) format accepts 16x9 files. They show perfectly on DCI projectors, only with 100 pixels of black on either side of the frame, which are frequently blocked by curtains anyway.

If you are planning a project that will mostly live in streaming and online, and might show in theaters only a few times, 16x9 will just make your life easier.

Delivery

Delivery refers to the final stage of your project when you are delivering to a streamer, television network, or theatrical release.

This is typically your timeline resolution when you are working in Resolve.

You'll notice that there isn't a timeline setting for 12K files up there yet, even though Blackmagic is making a 12K camera.

12K isn't a settled-on release format, and while there is a pretty solid argument that it will eventually come, it's not common enough yet to show up in the prebuilt chart. In addition, there are frankly very few places to show even 8K work. 8K monitors are rare, 8K projectors even rarer, and for now 4K remains the dominant format for distribution and release.

It might stay that way for a long time. Television is still delivering HD broadcast, and switching from SD to HD in North America was a process that took years and a massive investment to move the technology over.

With the benefits of moving from HD to UHD much smaller (on the sizes of TVs people have in their homes), and the investment massive, it's going to be a long time, if ever, until the TV networks move over to UHD.

So... why 12K?

Since this article is inspired by the 12K camera, why shoot the 12K even if you aren't going to be able to finish in 12K, at least now? Well, there are two big reasons to consider it; oversampling and future proofing.

First, let's talk about oversampling. While you might end up finishing to 8K, having that extra resolution that a 12K sensor provides will create cleaner, crisper 8K images than a pure 8K sensor because of the process of demosaicing.

An 8K video file has 8,000 blue pixels horizontally, 8,000 red pixels, and 8,000 green pixels. An 8K sensor has only 4,000 green pixels and 2,000 each red and blue if it's Bayer pattern.

Even the 12K camera has 6,000 clear, 2,000 blue, 2,000 red, and 2,000 green pixels in horizontal resolution.

Processing turns those sensor pixels into your final image pixels, and the more resolution you can input to that processing, the more you get out at the end.

The other side of the argument is future proofing. When RED first launched the 4K RED ONE way back in 2008, they said folks should start shooting all their stock footage now in 4K to ensure it would remain profitable into the future. Today, in 2021, the market for 1080p stock footage is definitely going down and the market for 4K stock footage is going up. I have had more than one client who shot on the RED ONE and finished to 1080p in 2011 or 2012 come back to remaster the project to 4K UHD for new release platforms. 8K stock footage is definitely going to be a thing soon.

The hard drive space won't always be worth capturing in 12K, especially for projects like documentaries where you'll end up shooting thousands of hours of footage. One of the nice perks of the 12K camera is you can shoot 4K with the same lenses you shoot 12K.

But if you are creating a project like an indie feature or a commercial or music video where the hard drive storage space is manageable, there are really compelling arguments for capturing in the format, even if your current master plans are only for UHD.

Especially with an indie feature project—who knows, by the time you are finished with post, 8K deliverables might be inching closer to standard.