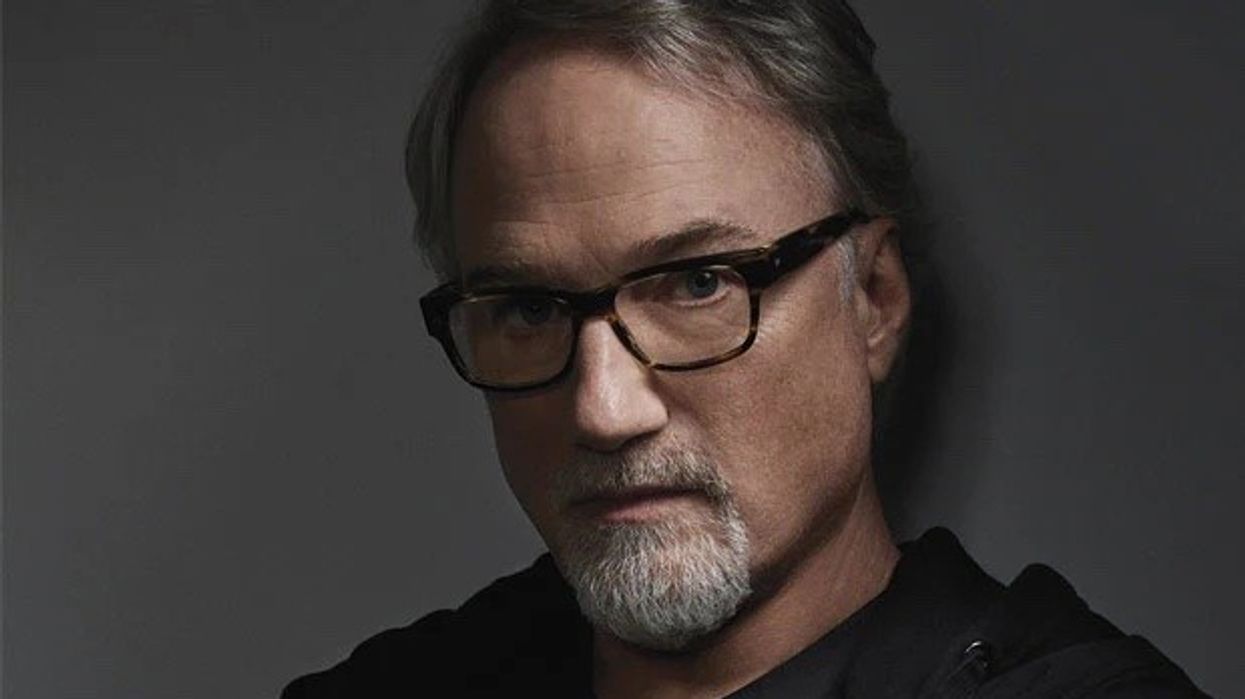

How David Fincher Crafts a Film from Your Obsessions

Human behavior is complex and fanatic, and David Fincher dedicates his work to uncover what makes us tick.

David Fincher’s films are glimpses into the director’s perspective of the world and himself. Through the actions and psychologies of all of the clockmakers, hackers, terrorists, detectives, and serial killers, there is a small piece of Fincher in there, obsessed with how his worlds look and function.

Adam Nayman writes in his new book, Mind Games, about Fincher’s films' complex visual tone, and the often misunderstood or dismissed works. From music videos to advertisements to Academy Award-winning films, Nayman critically engages with all of Fincher’s work to figure out why Fincher keeps returning to the same themes over and over again.

Nayman stresses throughout Mind Games that Fincher is essentially a dialectical filmmaker. His films are about colliding forces. When it comes to Fight Club, the moment of collision is so thin and subversive that it could make the movie feel smug.

Fight Club reveals its hand at the end, and the film can never be watched in the same way again. That feeling that had built up over the movie is gone with the realization that the film is taking itself seriously while you’ve been trying to watch it through a satirical lens. There is something that makes you roll your eyes at the subversive statement of the film that was made with high-profile stars for $60 million.

But maybe that’s Fincher’s point. Nayman points out that Fincher’s career is heavily influenced by his Smoking Fetus PSA in 1985. Nayman says in an interview with The New Republic, “When you talk about having it a couple of ways at once: You are instantly being Stanley Kubrick, one small ad commission because you are doing the Star Child—and it means more to have done 2001in 1985 than now.”

The ad was upsetting and created a strange sense of fear in response to the controversial work. Nayman says that this ad was a self-portrait of Fincher “because he’s a punky shit heel little 25-year-old smoking baby. It’s socially conscious, but it’s also so semiotically adept.”

Since the Smoking Fetus, Fincher has looked for that moment in each of his projects, that moment when you pull back and reflect on your choices.

Unlike Tarantino or Paul Thomas Anderson, Fincher feels more contemporary with his metaphysics focused on the ‘80s. While Layman's book doesn’t dive too deep into the biographical life of Fincher, Nayman discovered a defining moment for Fincher. The director was enraptured by a Making of The Wizard of Oz documentary.

“I love the idea that what got him excited as a kid was looking behind the curtain at a guy behind the curtain," Layman wrote. "He’s interested in unveiling authority, and he’s interested in illusion and showmanship…”

Fincher uses his power of illusion in Gone Girlto highlight our natural obsession with our outward personas. The film is aware of the extent that people go to manage how they are perceived by others through interpersonal relationships or personas fitted for social media. Rather than say, “People are always on their phones,” it asks us to look at the image we’ve created of ourselves and what we would do to protect that image.

Gone Girl is about self-stage managing an image of yourself and not wanting that image to get hijacked and controlled by another person. Fincher is constantly commenting on the way we live now and forces us to watch a story we already subconsciously know until we are too deep to get out of the hole. His work is unraveling and examining our obsessions.

Even in Zodiac, Fincher uses technology to bring you right to the edge of some kind of answer, but the more you know, the more you descend into a hell of your creation. The more answers you want to an unsolvable issue, the further you look and lose yourself. Fincher seems to enjoy that inevitable dissatisfaction, and it’s why Nayman says that Fincher’s work “[is] the cinema of doom scrolling.”

Fincher tells a story the way he sees it and asks us to trust him as he takes us on a journey of self-obsession. Fincher is interested in the procedures, repetitions, human behavior, and what makes a person tick before they explode. His curiosity in behavior is why his work is appealing and makes audiences reflect on themselves. We become the subjects of his story, and we are both entertained yet horrified by ourselves.

Source: The New Republic