How a Filmmaker Shed Light on China's One Child Policy (and Her Own Personal Story)

A government's multi-decade mistake (?) seeks admittance and correction in this new documentary.

Imagine learning at an early age that your parents were wishing for a boy but instead, upon birth, received a daughter. Now imagine you're living in a country with a One Child Policy that highly discourages a second pregnancy (citing the growing population as a means to stick to one child per household). How would you feel?

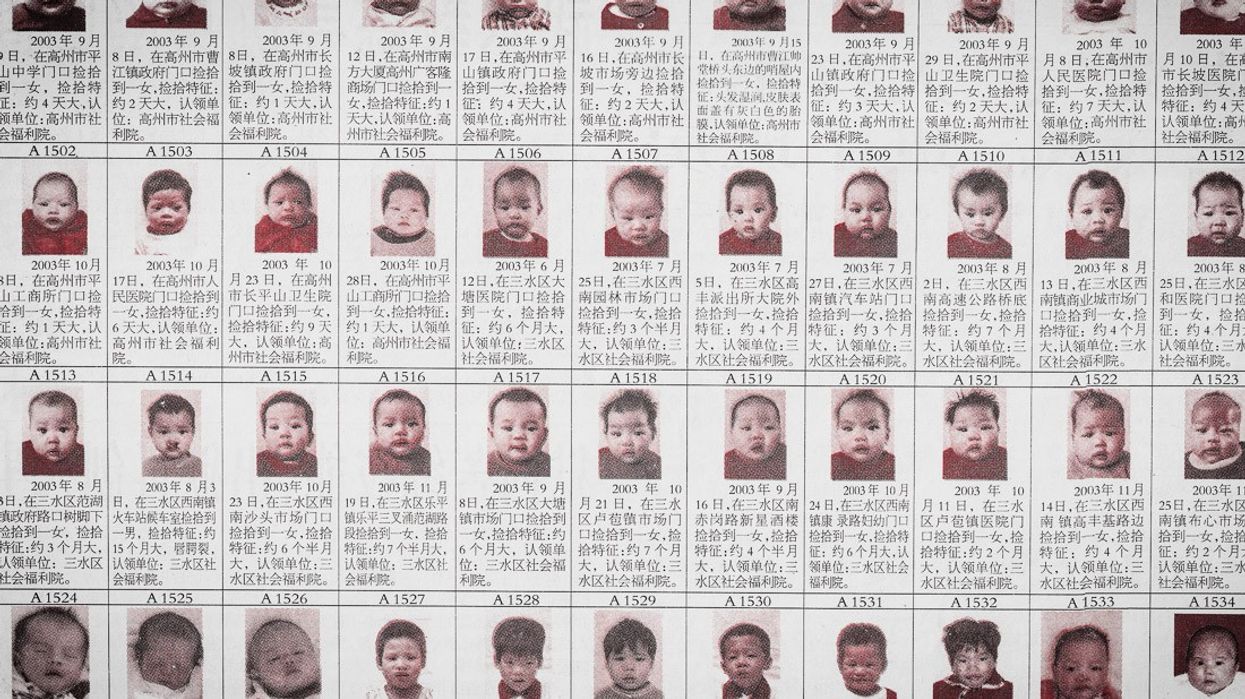

Chinese-born filmmaker Nanfu Wang's One Child Nation examines this deeply personal and political issue that grows more complicated the longer the film plays out. While Wang's family did ultimately have a second child (a boy), they were living in a rural area and were able to "get away with it." Not so for many other Chinese families, whose women had to either suffer unwanted abortions or forced sterilizations. All for the good of the "population war" that China was using as an excuse to torture women and murder children who were wanted by their parents. But policy is policy.

Wang and co-director Jialing Zhang interview many people affected by the now-defunct One Child Policy that separated and put a stop to burgeoning families. Midwives, human traffickers, photographers, American research facilities, and Wang's own family are but a few of the men and women the directors do not hesitate to ask the hard questions of. With Wang now a mother herself, the film takes on a feeling of being both urgent and reflective.

As the film premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, No Film School spoke with Wang and Zhang about their research of the One Child Policy, pitching the film, and the difficulty of interviewing family members.

No Film School: In lieu of asking how you came to this project, I wanted to ask you, Nanfu, what it was personally that made you feel that now was the time to get a film like this out into the world?

Nanfu Wang: When the One Child Policy concluded, it was in the news all over the place (especially in China) and in the international media too, and it was celebratory, like, "the One Child Policy is over now!" No one had mentioned the human rights abuse, or the consequences of the policy, and the people simply wrote it off, like "Now China's great, the policy is lifted!"

It held the attention of the media, the center of the media. It got me to think a lot, and then very soon, not long after, I was pregnant with my child, and so that became much more personally motivating, and it and got me thinking way more than I had before. Suddenly, I could understand what the women and children might have gone through, just a tiny glimpse of what they might have felt or experienced, based on my own experience.

NFS: And Jialing, how did you come aboard the project and what are some of the advantages and difficulties of working on a project this personal?

Jialing Zhang: When Nanfu reached out to me for the project, China had already started a Two Child Policy, and I thought, "Okay, there's a sense of urgency now, that we need to do the story right now, because this story is already entering a new chapter." That's when we started to work together.

I share a lot of feelings that Nanfu did, because I also have a sibling, and it took me a long time to identify the shame that the government had planted in me, through school, or propaganda on TV, the "Oh, you have siblings, your parents are selfish, they didn't consider the greater good of the nation" argument. So I share a lot of feelings that Nanfu did. At the same, I have some advantages in that I can offer a different perspective [than Nanfu], because Nanfu is very close to her family, so working together, we can share our stories and [each] offer a totally different perspective.

"Our biggest fear concerned their families, or that their daughters would not be able to go back to China to visit."

NFS: When building your Chinese crew, how important was it to feature only men and women born under the One Child Policy?

Wang: This is actually very interesting, because we did a film a lot in America, like internationally, and early during our production, in early editing, we had characters who are adoptive families. We actually identified someone whose adopted daughter was taken by human trafficking in our film, whose name appeared in the child record. It's like such a direct person, and eventually what happened was that I pitched the film at IDFA, and they wrote an article on the film and talked about how critical it was going to be of the One Child Policy. I think some of our subjects in America [knew of] my name, and the [tone] of the article, and realized that the film was going to be negative or at least critical of the One Child Policy, so they were very concerned that they would receive a retaliation from the Chinese government.

Their biggest fear concerned their families, or that their daughters would not be able to go back to China to visit. The other concern is they would be taken, or that some kind of governmental intervention in America would occur, sending those children back to China, after the film was exposed. It disturbed the adoption community. A lot of the adoptive families sent emails, messages, to me, asking me to stop making this film, to stop exposing their problems, and it actually shocked me, because I always thought the censorship stayed in China, but I didn't realize the reach was so far and wide that a lot of Americans—people who are not subject to the Chinese government—are actually self-censoring themselves, in the way that they chose not to be in the film.

NFS: As you both researched the history of the One Child Policy, did you find it to be an anti-female endeavor? The film does more than hint at this throughout.

Wang: I really don't think it was anti-woman...I think it was anti-human. I think it values so little human lives, as it's putting the social and government agenda above everything else, above individuality, above everything about humans and humans' rights. And not only were the women sterilized, but a lot of men were as well. The government treated humans as a production tool of the economy. They did not respect them as citizens.

NFS: Nanfu, you interview several of your family members in the film, including your mother. She's staunchly pro-One Child Policy and felt that it served the population well. When conducting an interview with someone you know so well (but whom you may not agree with) do you have to fight within to let her speak her mind and not challenge that?

Wang: Absolutely. I think I would argue with my mom on camera, but at a certain point, I had to give up because I realized that I was not going to change her mind. Even now that the film is out, she saw it, and I asked her, "What do you think now?" And she was like, "the One Child Policy was still necessary." After you've seen all of this, how can you still believe so? Her mind has not changed, although she did say that I'm glad that I recorded the history because in several years, people would forget it, so that's a positive, and she endorsed that.

But I think it's good, because I didn't start out to make an advocacy film in order to change certain things. I think the policy and how people lived through it, or responded to it, was so complex that it wasn't just black and white. It was filled with the education they received, the culture they lived in, and their upbringing, and everything is compounded to the point that it affected how they would react to it.

Zhang: I was there when her mom, after watching the film, expressed to us her feelings, and she said that the film was so true, and so valuable to history, and yet she still thought the One Child Policy was correct.

NFS: How did you sort through the archival propaganda footage that populated China's TV commercials, billboards, and sidewalks for decades? How much of this material has been "erased" since the Policy concluded in 2015?

Wang: I think it is disappearing, for sure. They're cleaning the internet.

Zhang: Yeah, they are cleaning the internet. If you go to the national library, there is so much footage, but it's difficult to get a copy of it.

Wang: Luckily, one person that we encountered, who we interviewed but didn't include in the film, was a collector (a lot of the items that you see in the beginning are his, such as the snap boxes, the matches, and the calendars). He has like four rooms of the items that he collected over the years, and his dream was to open a One Child Policy museum, if one day, when the Chinese government was not [in control], so having a person like him was super valuable, and we were lucky to find him.

"We'd have many copies [of the footage] whenever we'd shoot in China, and whenever we could, we would ship, for example, one copy to our friends, hide one in the house, and have one with us at all times, so in case we lost one, we wouldn't lose everything."

NFS: At the Q&A for your world premiere screening, you both mentioned the dangers of traveling in China and of having to hide your footage at certain checkpoints for safety reasons (and so it wouldn't be confiscated). Could you elaborate on the personal dangers involved in a production like this?

Zhang: We'd have many copies [of the footage] whenever we'd shoot in China, and whenever we could, we would ship, for example, one copy to our friends, hide one in the house, and have one with us at all times, so in case we lost one, we wouldn't lose everything. Anything can happen, you know? You go out and then you get stopped by police, etc. and so we had to be very creative and take a lot of caution.

Wang: When we got back to America with our copy of the footage, we didn't know if anything was going to happen to the footage at customs, or if anything was going to happen to us. And yet we knew that there was always that copy back in China that wouldn't be deleted, or, at the very least, wouldn't be deleted until we knew were safe with our footage here.

Zhang: Although there was one time where I finished a two-day shoot and I shipped a copy out that never actually arrived at my friend's house. I don't know what happened. It was just suspicious, but luckily, we didn't end up using that story, and I had other copies of the footage.

Wang: The footage, like the drive itself, disappeared during the process of one shoot.

Zhang: It just never arrived, and later I found out that my phone was being monitored the whole time.

NFS: Were you in fear of being followed?

Wang: Or of being taken away. What they usually do is: if you are caught and they take you away, the first thing they do is confiscate any communication tool you have, so if that happens, at least the GPS has been tracking [my whereabouts], so Jialing would know where I was at any particular time.

Zhang: I could send help, or, depending on how long she'd go missing, we could take different actions. Luckily we are still here, so, it's okay. It just takes a lot of caution.

Wang: There were times where I'd be at an interview subject's house for longer than we had initially planned, and Jialing was getting concerned, like...

NFS: "Why are you still there??"

Zhang: But I couldn't text her because what if her phone was confiscated by the police?

Wang: She contemplated whether to even contact me because what if the phone is not with me?

Zhang: I couldn't text her, so I'd then just have to wait.

"It was a huge challenge to balance the personal story, and then the national story, and to intercut between the two."

NFS: While editing, was it difficult balancing your personal story with the political one?

Wang: It was a huge challenge to balance the personal story, and then the national story, and to intercut between the two. Because unlike the other films that I've made, which I was a part of, this is about the artists' lives, the officials' lives', and the traffickers' lives. Besides the fact that I was interviewing them, I did not participate in those stories, so there is a difference. The participatory thing was not happening, so it was always a challenge of how to transition from my personal story into a bigger broad story, and how to intercut them and where they should come in and out. It took a lot of trial and error.

NFS: Nanfu, what has been the hardest and most rewarding thing about being a working mother within the film community? What have you learned along the way?

Wang: I've learned that being a mother is 10 times, maybe 100 times more difficult than being a filmmaker. That's been my experience, because I feel like, with filmmaking, I at least have a better sense of what's working and what's not. I have a sense of story and of judgment.

With a child, every day is different, and every day the problem or the issue that I'm facing is new. There's no formula to knowing if what I'm doing is right or wrong, so that's hard, but I think I'm glad that's possible. Although, there were numerous times where I had to take my son with me on conference calls, and he would be screaming to like six other people.

Wang: He would bite my hard drives, so I had to wrap them in my carrier, and then edit, and then he would undo my edits, smashing on my keyboard!

Zhang: He was an essential part of our crew. It was like having two babies over the past two years. [laughs]

NFS: It's like having your own child and getting a feature out into the world is another one.

Wang: I know! I think it kind of scares her to have a baby now. [laughs]

Zhang: I was thinking, "Wow, how am I going to handle that?"

For more, see our ongoing list of coverage of the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.

No Film School's podcast and editorial coverage of the 2019 Sundance Film Festival is sponsored by Blackmagic Design.