The Joker's Philosophy Reveals We're All Just One Bad Day Away from Super Villainy

The Joker is one of cinema's most enduring screen villains, but what are the philosophical roots of his gleeful destruction?

As long as there has been Batman, there has been The Joker. He made his debut in the first Batman comic, in 1940, and for almost 75 years, and through innumerable iterations, including four feature films (with the latest being Suicide Squad), this character has remained remarkably consistent despite the many writers, directors, animators and actors who have helped bring him to life. And any storyteller looking to create a villain should hope to be so lucky as to create a Joker. But what is it in the makeup (pun just noticed) of this villain that makes his brand of mayhem so singular?

In this video essay from Wisecrack, it is argued (plausibly) that The Joker is a nihilist of the existential variety, and before you throw tomatoes at me for being so pretentious, let me state my case. The Joker's appearance was inspired by the cinematic adaptation of Victor Hugo's The Man Who Laughs, a German expressionist film from 1928.

The version of the character who has had the most influence on pop culture is arguably the figure sketched out by artist Alan Moore in his 1986 work The Killing Joke (not to be confused with the current animated movie). It's here that the character acquires his backstory, though it's more of a series of stories, and in the 1989 Tim Burton film, Batman, an entirely new one was devised, with Jack Nicholson's Joker being a petty hood who was the man that killed Bruce Wayne's parents. This trauma led to the birth of Batman, and, years later, to his pushing Jack Nicholson's character into the infamous vat of chemicals. In Burton's world, the two literally give birth to each other, responsible for the other's existence.

In Moore's telling, The Joker is a failed comedian who, in one day, fails at his job, finds out his pregnant wife has died, is framed by the mob, and then, as if that weren't enough, falls into the infamous vat of chemicals (which should be more heavily guarded, probably). Wisecrack's essay argues that The Joker is a gleeful nihilist because he realizes that everyone is only "one bad day" away from becoming like him, one to whom everything is trivial, with no sense of the difference between good or bad. Everything is equally trite, and equally amusing.

"The cause of laughter in every case is simply the sudden perception of the incongruity between a concept and the real objects which have been through...laughter itself is just the expression of this incongruity."

The connection between humor and evil has been explored at length, notably by Arthur Schopenhauer in The World as Will and Representation, when the philosopher says "laughter in every case is simply the sudden perception of the incongruity between a concept and the real objects which have been through." And John Marmysz, in his work Laughing at Nothing: Humor as a Response to Nihilism, posits that for a character like The Joker, a man who has (maybe, because he changes his story all the time) been subject to the awful whims of fate, humor is a way to "understand life—as part of a cosmic dream that is pleasing in its ultimate absurdity." This is what makes him so unnerving: as the video argues, other villains "combat good with its opposite, while The Joker destroys good."

Introduced in 1940, a year and a half before the U.S. entered WWII, he reflects the sense of madness and doom that afflicted a Western world facing two inconceivable conflagrations in the space of 20 years. Both Bruce Wayne and The Joker are victims of shattering existential crises, and the video essay argues that the ways they choose to deal with these forms them. In the words of the video essay, "By introducing oppressive justice and order, [Batman] has thrown the moral universe of Gotham out of balance and created a new opportunity for chaos and evil to appear." He gives criminals, in the words of French theorist Baudrillard, "a more extreme version of order for criminals to subvert and challenge." Lest things get too serious, though, there's also the 1960's version of The Joker, who was not nearly so philosophically fraught:

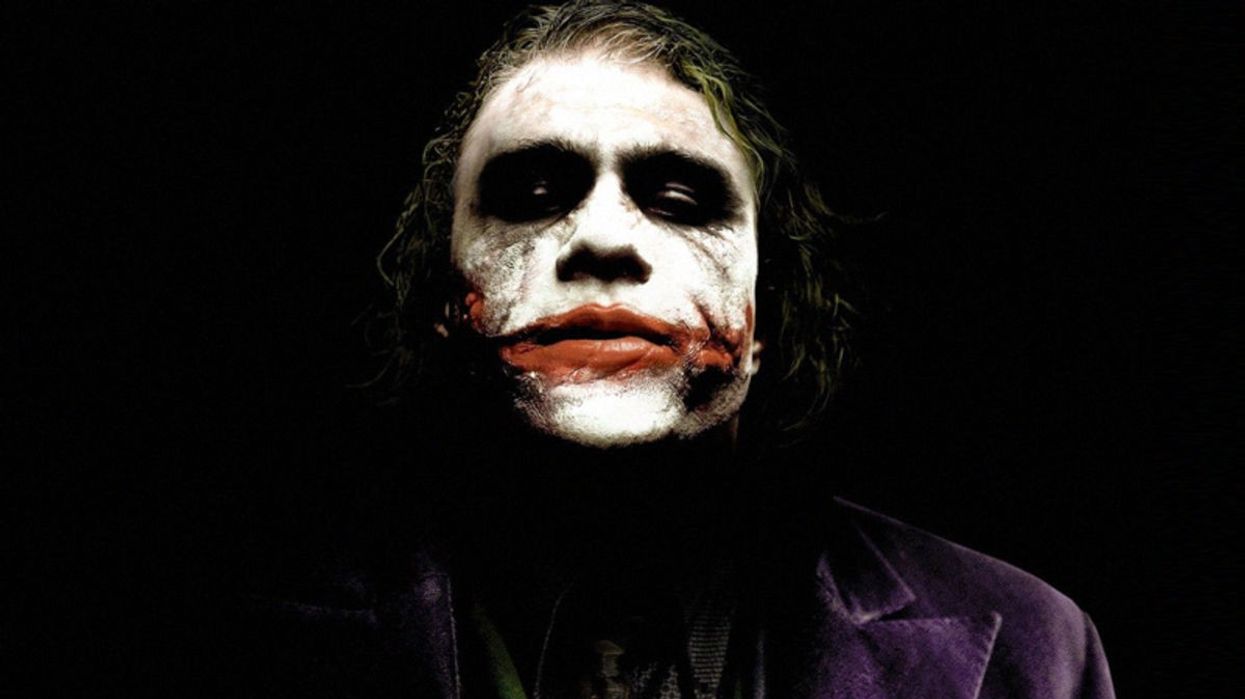

In this iteration, The Joker is more mercenary, interested in money, though he still retains his nihilistic essence. That essence, though, wouldn't find full expression until Heath Ledger's disturbing performance in 2008's The Dark Knight. The Joker came into his own as a character: truly frightening, ugly and oddly plausible; a force of chaos let loose in the 21st century, devoid of logic or pretense of cause and effect.

With Jared Leto playing the criminal with the rictus grin in Suicide Squad, the tradition looks to continue, as The Joker continues to walk the earth, attempting to convince others that they are just like him. As the laughing man said in Alan Moore's 1986 work, “All it takes is one bad day to reduce the sanest man alive to lunacy. That's how far the world is from where I am. Just one bad day."

Any writer could take a lesson from this: it's classic tragedy, and so, in a way, it makes sense that the citizens of Gotham are enraged with Batman, who, as a tragic hero, has brought this on himself (in this particular version of this universe of the story, of course). But Bruce Wayne's conduct is selfish: The Joker fills the vacuum left by the crime Batman obsessively cleans up. The Superhero calls the Supervillain into being by disturbing the order and balance of good and evil. In this way, The Joker transcends the world he was created in and becomes a symbol, a troubling philosophical notion that obviously affects the audiences who continue to watch him, in his own words, "chase cars."

Source: Wisecrack