To Be A Great Cinematographer, You've Got To Be An Inventor

The ASC specifically lists one of the duties of a cinematographer is “to invent needed tools.” Here are two of our favorites.

Way back when I first read the ASC list of a cinematographer's duties, my buddy and I had a little chuckle at “invent or cause to be invented needed tools.” Why would a DP need to be an inventor? My teacher, the wonderful Chris Comyn, ASC, pointed out that even if it seems ridiculous at first, it is actually essential: everything we use on a film set was invented by somebody, and DPs themselves came up with many of those things over the years. Somebody had to make the tools of the trade, why not the cinematographer?

The DP, after all, is involved in creating images: if a new tool needs to be invented to make creating that image possible, then it’s the DPs job to make that happen. Sure, Arri and Panavision and RED have invented a lot over the years, but sometimes it’s the person in the trenches who has the clearest understanding of the tools they need.

In honor of that often under-appreciated cinematographic duty, here are two items invented by or with cinematographers who we love.

While the cinematographer has always had a lot of control over the image, the lab, which was run by the studio, also implemented some image control, towards the goal of creating a “house look.”

1. Gregg Toland: The Color Chart

Though it would have been referred to as a “lab test board” at the time, it served the same purpose as what we call a “color chart” today. It wouldn't have had color swatches like the X-Rite ColorChecker since he largely worked in black and white, but the purpose was identical.

During the heyday of the Hollywood studio system, every studio had its own lab (and camera department, actually), but not entirely how we think of a lab today. A modern film lab has a set of standards that it adheres to when processing your footage. There’s isn’t really a “Deluxe” look or a “Fotokem feel” to footage. Their processing is designed to be largely neutral.

Not so in the '30s. While the cinematographer has always had a lot of control over the image, the lab, which was run by the studio, also implemented some image control (longer/shorter time in the bath, different bath temperatures, etc.), towards the goal of creating a “house look.” Since cinematographers were under contract to studios just like stars, the cinematographer could get to know how their footage would be developed and cater how they shot to how it would be processed.

But if you were a big enough cinematographer to get loaned out to other studios (as Gregg Toland was), and you had a real interest in controlling the way your footage turned out, you needed a way to communicate your directions to the lab. You could always send along notes with the film, but as many filmmakers have learned, language doesn’t always address images well. You might say “darker” and the post folks make it really, really dark. Or just a hair dark. Better ways of communicating were needed.

From this struggle, the Lab Test Board was born. Working closely with labs, and also with Kodak (who regularly sent a representative to Toland’s set as they worked on Plus-X and Super-X film stocks), Toland devised a system for fool proof communication with the person supervising development. Shoot a test chart, expose it in a controlled fashion, and ensure the lab prints it properly. If they print your board properly, you know they’ll print the rest properly. You can even trick the system: want your footage darker? Over-expose the chart. They'll print the chart down, and the rest of your footage will get darker along with it.

We see the descendants of this technology in video charts we shoot to this day. In fact, the newest versions of Resolve allow you to auto-calibrate your footage to a color chart, taking the human hand out of the image during post and leaving control on set. Of course, we still send notes from set to the colorist, and we can pre-grade stills or get the colorist on set if possible, but the color chart remains a staple of the cinematographer's toolkit to this day.

Storaro didn’t like HMIs, or fluorescents for that matter, since the limited spectrum of the light provide the color reproduction and personality he was looking for.

2. Vittorio Storaro: The Jumbo Light

We mentioned this in the podcast last week, so I wanted to dive a little bit into Vittorio Storaro’s invention of the Jumbo Light. Storaro is a cinematographer with a very strong aesthetic that is driven by an expansive philosophy of lighting, and to execute on his vision he developed a very specialized lighting tool.

One of Storaro's guiding principles divides light into “puntiform” sources (point-source) and “multiform” source (broad source) lights. You can get a single source of light by using a single bulb, of course, and at the start of his career the Carbon Arc often served that purpose in his lighting. It’s a large light, with a single tiny arc giving off your light, so you get a crisp, clean shadow. For a variety of technical reasons, however, the Carbon Arc started to lose prominence in the late '70s, and big HMI units started to take its place.

Storaro didn’t like HMIs, or fluorescents for that matter, since the limited spectrum of the light provide the color reproduction and personality he was looking for. He wanted broad spectrum lights that were capable of creating his desired puntiform light, and couldn’t find them. So, he went to Iride SRL in Rome and worked with technician Filippo Cafolla to modify Aircraft Landing Lights (ACLs) for film usage. By assembling them into a unit for 16 of the 28-volt lights to be rigged together, then wiring it through a dimming board and running it off 220Volt power, Storaro created the source that would give him what he needed: a light with a broad color spectrum, dimmable and switchable remotely, with the punch to be placed far away.

The punch is the key. By using ACLs, designed to send light far out into the distance (specifically to aircraft up in the sky looking for a runway), Storaro is able to put the light further away from the subject. The further the light is away, the smaller its relative size. (Think about the sun, which is way larger than the earth, and how small it seems because it’s so far away). This helped Storaro in a few ways, most significantly by helping to minimize the multiple shadows created by the multi-unit source, which we all deal with when using sources like the maxi-brute. It also gives the light the appearance and shadows of a single sourced light.

But that's not all with the punch. By being able to place the image further from the subject, the light starts to more realistically mimic the sun. Because of the inverse square law of light, the closer you get to a light, the more dramatically it falls off as you move around. Place a light right outside a window to mimic the "sun" and the audience doesn't buy it, since as you walk up to a real sunlight window, exposure doesn't change much at all, but as you walk closer and closer to a lamp, it gets hotter and hotter on the subject. Of course a jumbo can't get as far from earth as the sun, but it can get far enough to work as a suitable sunlight replacement. Jumbos also work closer to the subject, often through a diffusion to smooth out the multiple shadows.

The lights aren't exclusively used by Storaro. They are available for rent (primarily in Rome), and other DPs have a taste for them, including fellow Italian Nicola Pecorini, where you can see them in the still from Lost in La Mancha, above.

What are your favorite cinematographer-driven inventions? What tool would you like to invent to make your life on set easier?

Big thanks to Craig Mieritz of https://ubu-roi.com/, a talented Bay Area filmmaker, a buddy, and a man who is clearly very happy to get to use a Carbon Arc.

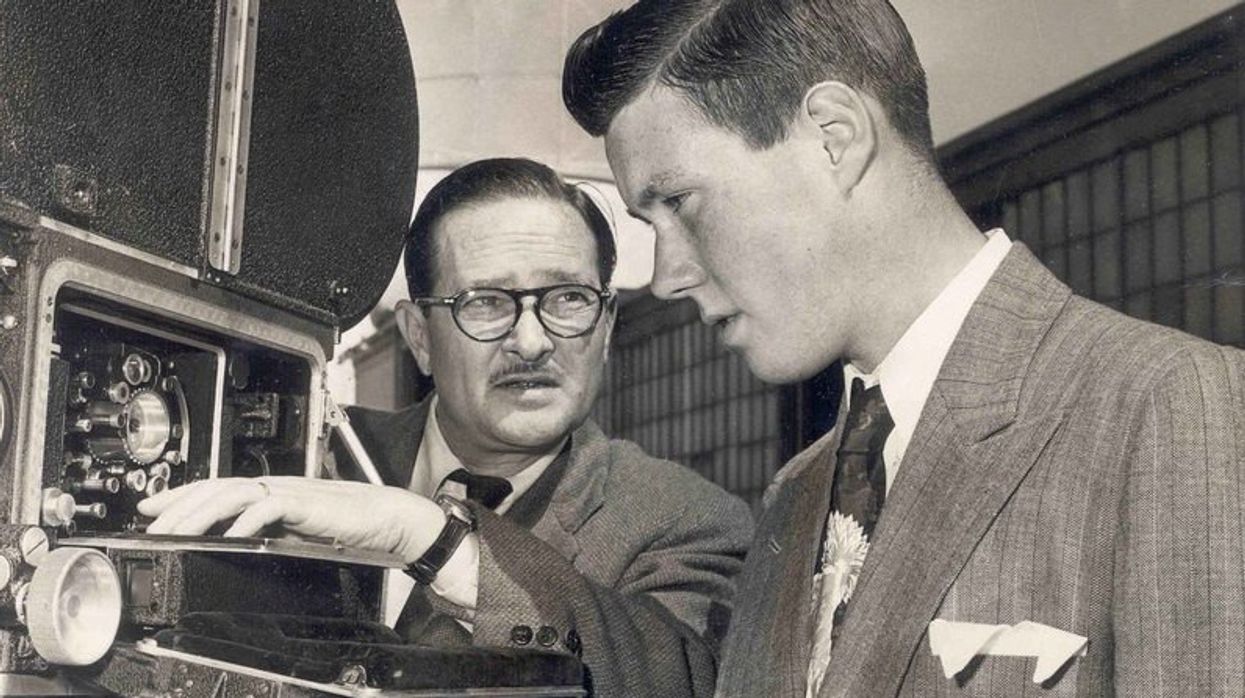

Featured image of Gregg Toland. The Toland section would not have been possible without a text only available in library form: Wallace, Roger Dale “Gregg Toland – His Contributions to Cinema,” University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, 1976. p. 35