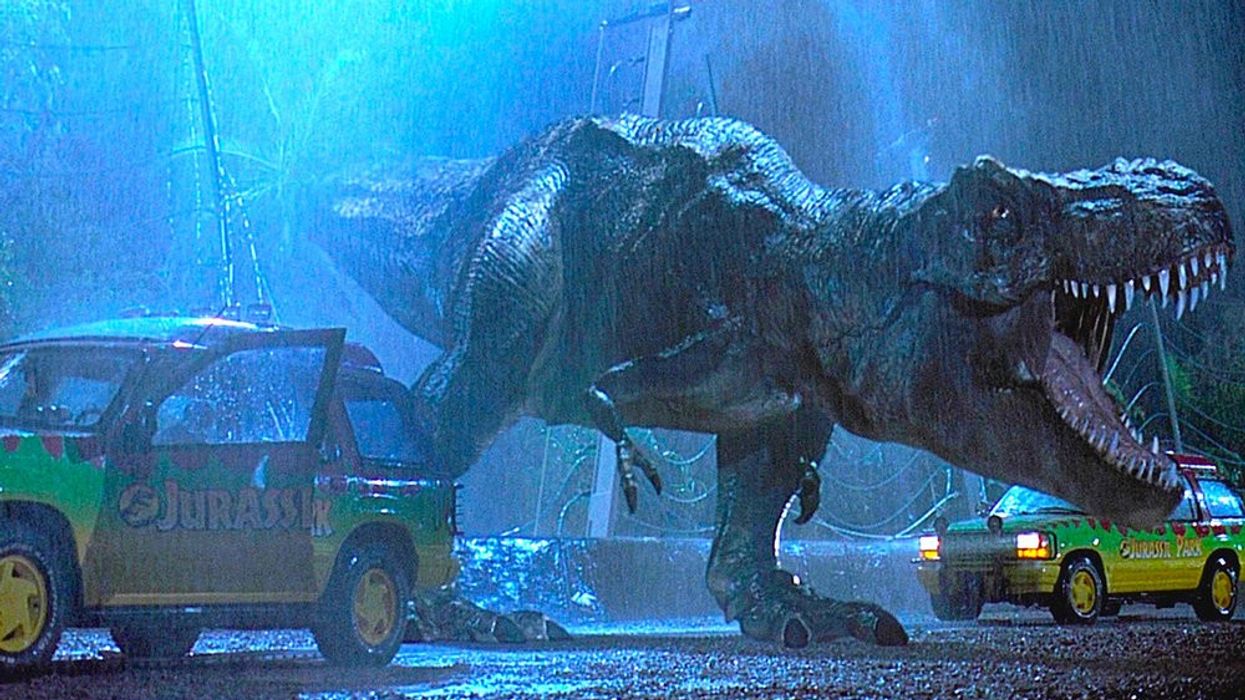

Watch: Why the T-Rex in 'Jurassic Park' Sparked a VFX Revolution

This video breaks down one of the most famous Jurassic Park sequences—including the moment when computers started to win the war at the multiplex.

Cinema is a language, and just like some people can pick up French in two days, Steven Spielberg, from his earliest work, has demonstrated an innate mastery of film grammar. No matter the genre, Spielberg knows how to not only tell a story, but to make an audience feel what he wants them to. He also has been at the forefront of using technology to make this movie magic happen. In this essay from CineFix, one of the most famous scenes from Jurassic Park is broken down point-by-point, to show just how a classic movie moment was made, and how realizing Spielberg's ill-advised theme park changed modern cinema forever.

Before its release, Jurassic Park was already legendary from its trailers, which hinted that this movie was going to have some of the most realistic VFX monsters to ever terrorize Jeff Goldblum. But, you don't just throw a big CGI dinosaur into a shot and get cinema magic (though, you can put Goldblum into any shot and get something pretty close. That's movie science.)

The decision had been made that humans were to be subordinate in this film to the effects.

Now, in the scene in question, the audience has yet to see the T-Rex, and Spielberg is very deliberate about how he reveals the King of the Tyrant Lizards. The dinosaur was brought to life by legendary effects houses ILM, Stan Winston Studios, and stop-motion deity Phil Tippett. Tippett's biggest contribution, which he developed in the '80s for the Star Wars films, had been to push stop-motion animation to its limits; instead of the normal series of still images, a quasi flipbook that, while very cool, was not really realistic in portraying the physics of living things, Tippett introduced the optical phenomenon of motion blur, or, "that moment of fuzziness...when an object moves faster than the naked eye can track."

Tippett's process, which he titled "Go Motion" because naming things is not that easy, changed the entire idea of what could be realized on film. Foregoing the process that had basically been the same since King Kong climbed the Empire State building, Tippett's technique, while a leap forward, was still pretty old school. He induced a slight movement in whatever needed to move, in the instant before it was exposed. In this case, the objects in question were ILM and Winston's computer controlled models, which were beefed up versions of Tippett's puppets. Spielberg quickly appreciated the direction of his long-time collaborators as a way to bring Michael Crichton's novel to a blurred and moving life; his understanding of VFX and cinema have consistently enabled him to implement technology in the service of narrative.

Jurassic Park began with a strategy: Tippet would make small puppets, augmented by Winston's animatronics, then brought to life by the work of ILM, whose task was to tie it all together by compositing, augmenting the motion blur, and sprinkling its digital wizardry to make the final product (which, remember, was still a celluloid-based entity) as real as a movie about creatures that no one has ever seen could be.

"The character had to feel 100% real, or the film just did not work." -Shane Mahan

As Creature Designer Shane Mahan is quoted as saying, regarding the King Dinosaur, "...the character had to feel 100% real, or the film just did not work." Which must have made the human actors feel pretty great. But Spielberg was crossing a line that's even more relevant today, namely: can you create something utterly fake, spun out of whole cloth, and make it mean more to people than Jeff Goldblum? Pre-production had already been underway for 24 months, and the decision had been made that humans were to be subordinate in this film to the effects. This might not have been the first time a film was so effects heavy, but it was certainly the case on such a grand scale, and, furthermore, with such cutting-edge VFX and animatronics.

Winston's models could take 16 weeks, with valves through which 60 gallons of liquid a minute were forced, to give the skin an illusion of motion; just one could weigh upwards of 13,000 pounds. Suffice it to say, it was clear to everyone that this was not going to be an ordinary film, even by Spielberg standards. This was not Jaws. Spielberg did not want dinosaurs that looked like "B-movie monsters" and so the concern, from the beginning, was on what could not be filmed. The actors were there to react to phantoms, to be the audience's proxy, but without truly revolutionary visuals, there would be nothing for the characters to plausibly be terrified by, and, therefore, nothing to overwhelm the audience. Really, though, it was a pretty simple problem: all they needed were effects which had never been produced before.

Before the shoot was set to begin, Spielberg brought a paleontologist, Jack Horner, onto the film, to consult on dinosaur behavior. At the same time, Tippett was making storyboards that didn't exist as drawings, but clay movies, in order to capture the motion of the creatures that would be the real stars. Horner found Tippett's work to be incorrect, because in his opinion, Tippett's depiction of the pre-historic creature's movement as reptilian was wrong. Horner was adamant that dinosaurs were far more birdlike. Ultimately, ILM used this opportunity to push their new Apple computer-driven system of microprocessors (which had just made the T-1000 in Judgment Day turn into all sorts of deadly stuff) as a solution to the problem of bringing Winston's models to life. Thus, T-Rex and co. became living, breathing, creatures that stunned the world.

After Spielberg saw the footage of the models, he knew what he had on his hands, and it became one of the most important moments in film history: This was the film when computers truly overtook the human element in movies—when effects like Tippett's home-grown work (though it did make it into the final T-Rex scene in some form) became less and less important. Tippett, for his part, has always adapted, and has integrated himself into the workflow of digital productions, partly because he has no choice, and partly because even digital needs a human touch.

"From then on, if a director could dream it, a computer could create it."

The digital salvo had been fired, and film would never be the same, especially after the first entry in the franchise was released in 1993 and earned $81.7 million dollars in its first week, surpassing its budget by almost $20 million. Fittingly, Spielberg, who, along with Lucas, had introduced the "blockbuster" to Hollywood in the late 70s, brought movies into yet another era; and therein lies the chief irony of this story. Spielberg arguably loves film more than anyone else, and he is beyond respected by his peers. Perhaps it's the purists who are wrong, and those like Spielberg who understand the secret that movies, like life, are impermanent. Thus, if new technologies can be used to entertain and to make movies, then why not use them?

There will always be those who decry the movement towards the digital future, but Spielberg is a hero to many, and his strategy of adaption seems to be working out for him. As this video shows, the birth of the first computer-driven blockbuster is a movie all in its own right, and one populated by fully human protagonists.

Source: CineFix

'Anora'Neon

'Anora'Neon Annie Johnson Kevin Scanlon

Annie Johnson Kevin Scanlon