Planes, Helis, and Drones: How the View From Above Changed Cinema

A brief history of how we learned to fly the camera.

[Editor's Note: We asked Sasha Rezvina to write this post due to her work with Aerobo drone company.]

Two silhouettes are huddled next to each other, remote controls in hand. It's golden hour, and while one is staring at a monitor attached to their control, the other is squinting at the flying camera. The camera, the RED Weapon carrying Ultra Prime lenses, is 800 feet in the air while flying at approximately 30 miles an hour. The pair has the words “Drone Crew” stitched across the backs of their t-shirts.

Within three hours, production will have a stunning establishing shot to weave seamlessly into the narrative of their film.

But aerial footage was not always so accessible to filmmakers. This same shot once cost production upwards of 50 thousand dollars and often cost stuntmen their lives. From to jet planes, to helicopters, to drones, we've been attempting to strap wings to cameras since the dawn of cinema.

And not for nothing. Being able to move the camera fluidly in 3D space gives filmmakers more freedom with how they tell their story. Camera flight allows cinematographers to capture longer distances, unique perspectives, and fast movement. Here are some highlights from the surprising history of aerial cinematography.

The first application of aerial cinematography was to put audience members into the action of war.

The birth of film and flight

After World War I, the U.S. had thousands of highly-expert, out-of-work pilots— and about 100 million people who still had the bitter losses and victorious memories of war on their mind. In short, the burgeoning film industry had everything it needed to tell a damn good war story.

Naturally, the first application of aerial cinematography was to put audience members into the action of war. Flying cameras were necessary to capture flying subjects.

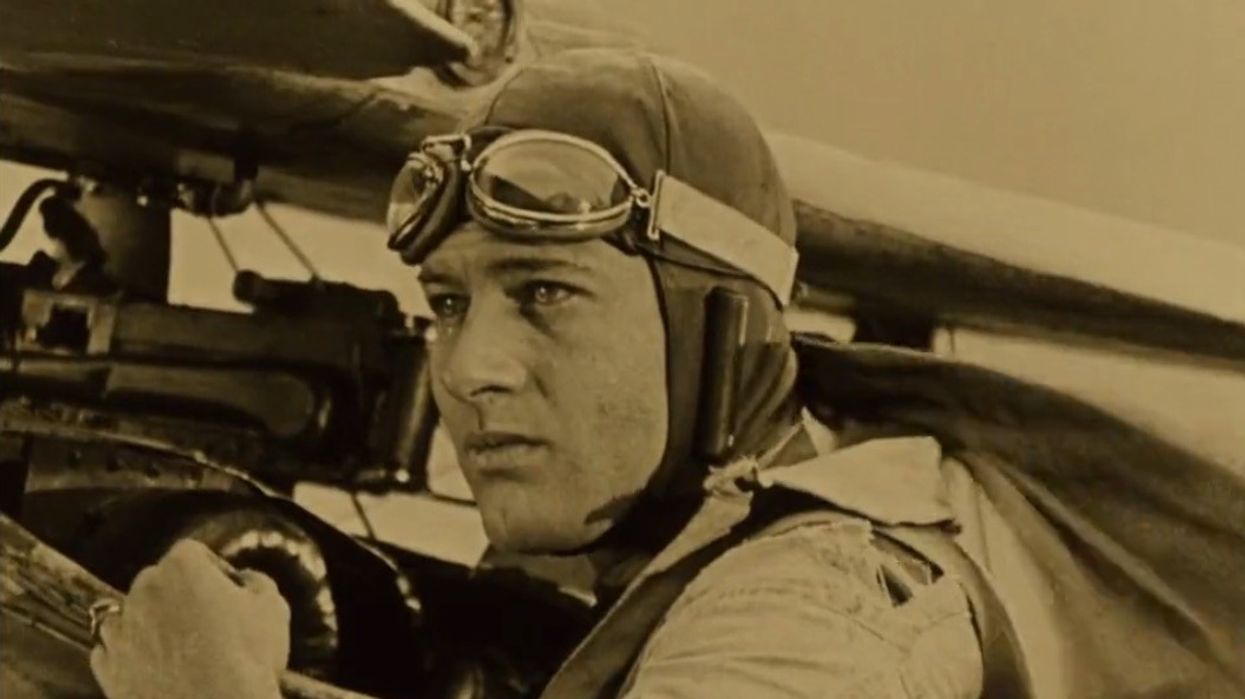

Wings (1927) contains the first—and many would argue still the best—dogfight scene in cinematic history. Bold aerial cameramen had to fly alongside the stuntmen to capture the scene, earning the film the first ever Oscar in the “Best Picture” category.

The scene was convincing, in part, because the stunts were dangerous. The actors weren't pretending when they jumped off the wings of a crashing airplane, and the cameramen were flying right alongside the action. These precarious scenes resulted in the tragic death of one pilot and the hospitalization of another.

The film was still a huge success, igniting a generation of war films with similar stunts. And the demand for both aerial stunt actors and the cameraman to film them established a film aviation sub-industry.

It was the invention of the gimbal that literally raised the ceiling for filmmaking.

The first flying camera platform

While a plane was the first device used for aerial cinematography, it was not considered a camera platform in its own right. Its speed and wind-induced shaking meant that it wasn't conducive to capturing action on the ground. It was the invention of the gimbal that literally raised the ceiling for filmmaking.

The civilian helicopter was invented in 1946—but a cameraperson might have flown in that helicopter before any paying civilian had. According to a 1945 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, the film The Bandit of Sherwood Forest (1946) had a custom-built helicopter with a camera in the cockpit to shoot the storming of the castle. Although the scene didn't make it in the final cut, it still marked the first film where a helicopter was used as a camera platform.

Aerial scenes often were excluded from films during the editing process. Although a handful of directors attempted to add an overhead shot to their repertoire in the late 40's and 50's, the footage was almost always deemed useless. Even the best pilot couldn't do anything about the helicopter's shakes and sudden movements that often compromised aerial footage.

A French camera operator named Roger Monteran finally came to the rescue when he was hired for the film The Longest Day. He designed the first camera stabilizer: a simple mechanical device that cushioned the camera with springs that dampened the vibrations from the helicopter. The scene below is one of the earliest captured by a stabilized camera in a helicopter, but you can tell the early stabilizer is still shaky.

Monteran's design served as a prototype for Nelson Tyler's more sophisticated stabilizer, which similarly isolated vibrations, but also offered more control over the angle and discrete movement of the camera. The operator, hanging off the side of the helicopter, could now pan, tilt, and roll a stabilized camera shot. You can see its early applications in the 1966 Batman:

And, most famously, in the long-take shot in Funny Girl (1968):

The Tyler Camera Mount cemented aerial shots as a part of cinematography. An aerial shot no longer required death-defying aviation stunts and thrill-seeking talent. Filmmakers had more options for where and how a camera is flown through the air.

It seemed as if aerial footage would remain a luxury in filmmaking—until Hollywood caught whiff of technological advancements to military drones.

The democratization of camera flight

Between the 60's and early 2000's, dozens of films used helicopters as camera platforms—but that was still less than one percent of the films that came out of Hollywood each year. Few productions could afford to rent a helicopter for a five-second aerial shot, and those who did were often disappointed to find that the regulatory (helis have to fly above 1000 feet) and technical limitations hindered their vision for an aerial shot.

It seemed as if aerial footage would remain a luxury in filmmaking—until Hollywood caught whiff of technological advancements to military drones.

In the mid 2000s, camera-equipped flying robots were making headlines for infamous Israeli reconnaissance missions and America's capture of Bin Laden. But in the years following, technological advancements made these drones more accessible to other sectors:

- LiPo technology improved the battery life of drones

- GPS positioning technology improved precise control over a drone

- Smartphone technology improved the quality of cheap sensors and computing power; and

- Brushless motors improved the durability and safety of drones.

All of a sudden, it became easier than ever to fly a camera.

Films like Skyfall, Oblivion, and Star Trek: Into Darkness were among the first to use drones as camera platforms abroad. When the FAA set up permitting for commercial drone applications in the United States, they opened up the floodgates. By the end of 2015, there were 1000 commercial permits and by the end of 2016, there were 20,000.

Initially, the drone was a cheaper, safer alternative to the helicopter, but recently the technology has evolved to be much more. The quality of cameras found on DJI's Inspire 2 drones and the stabilization equipment produced by manufacturers like Freefly has significantly changed what “flying a camera” means.

Closing the gap between filmmaker and frame

A drone isn't just used to get high-and-wide aerial shots. It can be used on the ground, chasing a character through a house, diving off a cliff, or circling the perimeter of a circus tent. Dexter Kennedy, chief pilot of Aerobo drone company, explains, “A filmmaker can now essentially place a camera anywhere in 3D space. They can replace a crane, a dolly, and a Steadicam with drone—and spend no time setting up any sort of rigs.”

And the best part? You don't need to be a daredevil to pull off a gorgeous establishing shot.

As drone technology improves, the technical and regulatory hurdles will decrease and more people will have the ability to get their hands on a flying camera. According to Brian Streem, CEO of Aerobo, drones will one day be part of any cinematographer's toolset. He predicts that “Most filmmakers will have a quadcopter case right beside their camera and lens kits.”

Featured image from William A. Wellman's 'WINGS' (1927)

Aerobo drone company is the largest provider of high-end aerial video and photography, having worked across 40 states and three countries.