'The Little Stranger': Lenny Abrahamson on Why Directors Shouldn't Pretend to Know Everything

Abrahamson also explains how he took an 'original approach' to a haunted house movie.

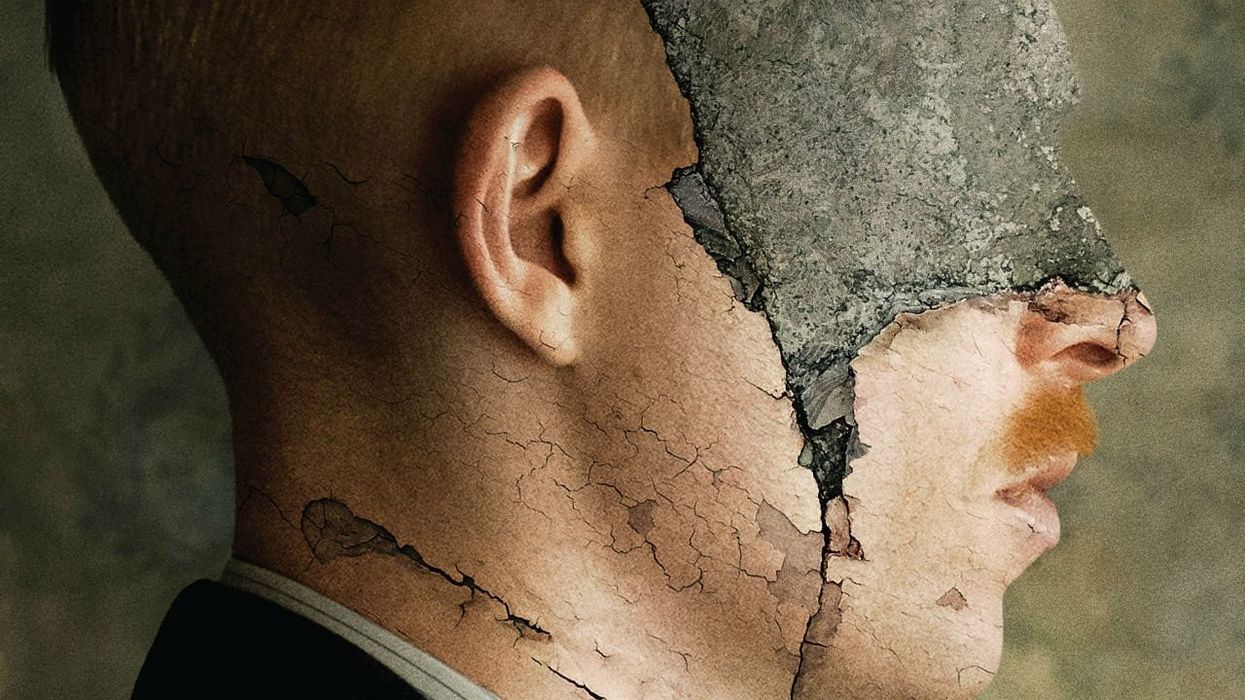

The Little Stranger is not your typical haunted house story. Though there are veritable ghosts lurking in the shadows, the real specters are within the characters themselves—and the spaces between them. Based on the 2009 novel by Sarah Waters, Lenny Abrahamson's film takes a subtle, restrained approach to gothic horror. An atmosphere of dread permeates the vast, decaying estate that may or may not be haunted, but the film is ultimately preoccupied with the humans who roam its halls.

Built in the 18th century, Hundreds Hall was once the zenith of aristocracy. But when The Little Stranger begins, in postwar 1940s Warwickshire, the manor has fallen into disrepair—a relic of a bygone high society. Dr. Faraday (Domhnall Gleeson), an upwardly mobile physician, remembers visiting the Ayres's estate when he was a child; his mother, a provincial maid, once worked there. Now, he's been called to the property to tend to an ailing housekeeper. Faraday discovers that the maid is not sick, but rather spooked by things that go bump in the night. Thus, The Little Stranger fuses horror with a shrewd observation of a critical moment in the history of the British class system.

No Film School caught up with Abrahamson to discuss how he infused his genre film with character, why the decision to light interiors brightly enhanced the gothic horror vibe, and why directors should often step back and let the actors take the reigns.

No Film School: Do you want to tell me a bit about what attracted you to Sarah Waters' novels?

Lenny Abrahamson: Well, somebody sent me the book when it came out. It just completely captivated me. That happens rarely to me.

When you start reading it, it's not for quite a while until you feel that there's anything supernatural about it, or that you're in a world with a ghost story. Initially, it's just fabulously observed character stuff. The drama between these people—this odd and fascinating world of the late '40s crumbling aristocratic Britain. And when you realize that Sarah had this other dimension in her head—that this character story is going to be framed within a kind of big house ghost story—that was really exciting for me. As a filmmaker, the challenge of doing something which does not fit neatly into any genre category was exciting.

I also found the book really moving. Again, for a book which has all these chilling, unnerving aspects of ghost stories, you don't expect the story to also be moving at the level of character.

"It's not like the audience is going to sit there and go, 'I'm in a standard haunted house environment. I know the rules.' We managed to take a more original approach."

NFS: That's actually what I loved most about the film—that it's not until about an hour in, if I remember correctly, that we even really put together that this is a ghost story. I loved that you spent so much time having the audience invest in the characters, so that by the time you reach that point, you're more willing to take that leap.

Abrahamson: Exactly. And if you spend too much time on the genre elements too early, I think you're creating this expectation for the audience that's that what this is. You have to, as you say, create this rich group of characters where people feel connected to them, and that's the real driver of the experience.

NFS: I thought Faraday was such an interesting character. He was very difficult to penetrate. How did you approach the character first on the page, and then with Gleason?

Abrahamson: You know, I worked with a brilliant writer called Lucinda Coxon. We spent an awful lot of time talking about the experience of Faraday. It's very important that we stay pretty close to him. He's the person who brings us into the world of the film. We see it through his eyes. Certainly, in the novel, he's the narrator. Films are not as rigidly connected to a single person's perspective as books are, but nevertheless, he is our guide to this world.

"It's always different when you get on set. It's never quite what you expect, and you have to adjust."

And Faraday's quite...he's got sharp elbows, if you know what I mean. He's a character who's quite repressed, and at the same time, it's really important that we want for him what he wants for himself.

Casting Domhnall Gleason was central because Domhnall is such a warm person as a human being. Having that warmth and that light allowed him to play pretty tough with Faraday—to really present a character that was quite kind of rough, and yet have the audience still stay on his side.

NFS: Did you work with him on set to build this out, or was most of this the architecture of the character built before you went into production?

Abrahamson: Well, myself and Domhnall talked about it a lot beforehand. I've worked with him before, so we're friends. We had a lot of big conversations about Faraday in the months leading up to the film. And then we did quite a bit of rehearsal as well, so we'd done a lot of the work by the time we got on set.

But then it's always different when you get on set. It's never quite what you expect, and you have to adjust. Actor and director have to adjust to the reality of the shoot. And so we were constantly discussing [Faraday], and adjusting him, and exploring him, and sometimes, on tape, pushing him further and then pulling him back. So it was a very collaborative experience.

"When you're shooting in a house full of reflections, you always get a hint of other spaces."

NFS: Can you tell me a bit about working with the production designer, and art directors, in terms of building the house? Because the house is a looming character in the film, as it is in any haunted story.

Abrahamson: Yes, indeed—the house kind of has a life of its own in this film. The atmosphere of the house reflects what's going on inside the characters.

We worked with a brilliant production designer, Simon Elliott, who has a very deep knowledge of British architecture, interior design, as well as a great storytelling instinct. We wanted it to be truthful, so it's not a super-heightened kind of style, but at the same time, it had to be expressive.

A tremendous amount of work went into how to create the interior and make it feel the way we needed it to feel. Simon was the one who introduced all the mirrors in the central hallway, for example, which is a very tough thing to shoot in that environment, because there's always the danger of catching the reflections of the crew in camera. But it did add hugely to the atmosphere. When you're shooting in a house full of reflections, you always get a hint of other spaces.

Abrahamson: Simon worked very closely with our location people so that the house that we found—which was such a huge decision—was the right one. We decided, for example, that we didn't want the cliché of having it be intensely gloomy and dark inside. We didn't want to go with the gothic, noir-ish kind of light and shade. We decided to go for a richer, more colorful palette. And at the same time, I think we managed to create an uneasy mood.

It's always great if you can create experiences without using the materials that people are used to, you know? It feels fresher. In this film, it's not like the audience is going to sit there and go, "Okay, so I'm in a standard haunted house environment. I know the rules." I think we managed to take a more original approach.

NFS: Do you think you did that with other elements of the below-the-line craft? It seems that you did with the cinematography, as well.

Abrahamson: Yes, absolutely. Myself, Ole Birkeland, who's the cinematographer, and Simon worked very closely. Ole made the decision to have no direct light at all in the film in any interior. None. It's all reflective. It's all bounced. And at the same time, it's moody.

We were always trying to stay on that line between the naturalistic and the heightened. We are creating an experience for an audience, but I think as soon as you do that too obviously, it stops being a powerful experience. In a conventional genre film, you kind of know you're being manipulated, and that's the contract, and it gives you a certain kind of experience, and that can be very enjoyable. But I think if you want to create something with real human meaning, you somehow lose something if you are too heightened in your design.

"We are creating an experience for an audience, but I think as soon as you do that too obviously, it stops being a powerful experience."

So we had to tread that line really carefully. We had inflected the storytelling and to shoot in a way which did create the kind of moods and foreshadowing and anxieties that we needed. But at the same time, we had to make it hard for an audience to just go, "Oh, yeah."

Also, the sound is of huge importance. The sound design is really a big part of what gives the house its atmosphere.

NFS: Would you say that gothic horror is the genre?

Abrahamson: Yes, absolutely. It's quite interesting. As soon as you go anywhere near something as strong as gothic horror, there's a big gravitational pull to that. And what we were trying to do all the time was not topple over into it, but stay skirting around it, and flirting with it.

NFS: How else did you work with the cinematographer to create some of the compositions that were in the film? Like you just said, you were able to take the anxieties of the characters and infuse the cinematography with them.

Abrahamson: Well, that's nice to hear. First of all, we did a lot of prep. So we went through the film very carefully. We did drawings and notes and had plans around most of the scenes. But the way I like to work is that I like to have that, but then I tend to diverge from the notes a little bit when I shoot. So I always have a plan, but then the more it develops on the shoot day, the more I tend to enjoy it.

"It's lit quite brightly. Especially in a period film which flirts with gothic horror, it's a very unusual choice."

But the preparation is always there. Even if we diverge [from the plan], it helped us sharpen and align our instincts, so that Ole and I were both drawn towards the same compositions. Quite often, we would both have the same feeling at the same time that the shot would be better a bit like this, or we should change that. So what you hope is that it becomes instinctual.

Abrahamson: It was similar with decisions about how moody to be in the lighting. For example, there's a big, long part scene about 20 minutes into the film or so, where the Ayres family invites some guests over. It's the first time in the film where something very dark happens. But actually, if you look at the way that the entertaining space is lit, it's lit quite brightly. Especially in a period film which flirts with gothic horror, it's a very unusual choice. But I think those are the things that give the film its personality.

"Directors should be prepared to go in there and let the actors be themselves for a while. Watch what they do. Don't leap in."

NFS: Coming from having directed Room, were there any specific challenges that you didn't foresee making the leap to a bigger production?

Abrahamson: Nothing huge. This is my first period film. It's very, very obvious, but when you're making something contemporary, you can pretty much point the camera in any direction and you can still shoot. But when you're filming period, everything has to be planned. You can't change your mind at the last minute. Everything has to be transformed back into what it would've looked like in those days.

But generally speaking, it was such a lovely cast, it was a really great crew on this film. I worked with all the same post-production people that I always work with, so it felt like a natural progression. It didn't feel like a big leap or anything like that.

Abrahamson: My advice to filmmakers generally in terms of working with actors—aside from anything to do with the specifics of the project—is to not jump in with the view that you've got to have every answer, and tell everybody everything, and then have them do what you say. It's so much richer—and you get so much more out of it—if you have all your prep, and you kind of know what you're moving towards, but you're prepared to go in there and let the actors be themselves for a while. Watch what they do. Don't leap in.

Some directors act this way out of insecurity, or the belief that you're supposed to know everything as a director. But be prepared to hang back a little bit, and watch, and see what it is that actors are doing, and what you can take from that, instead of going in with a shopping list of stuff and just telling everybody what to do.

In terms of the genre, I don't think I'm particularly qualified to talk about period genre filmmaking. But I think the more you think about character—and the more truthful that stuff is—the better your film will be. Even if you're making the most generic film, I think finding characters that people believe in is always important.

For more information on 'The Little Stranger,' click here.