‘A Prayer Before Dawn’ DP David Ungaro on Shooting Fight Scenes Up Close

For 'A Prayer Before Dawn' DP David Ungaro, physical involvement was the most important part of the job.

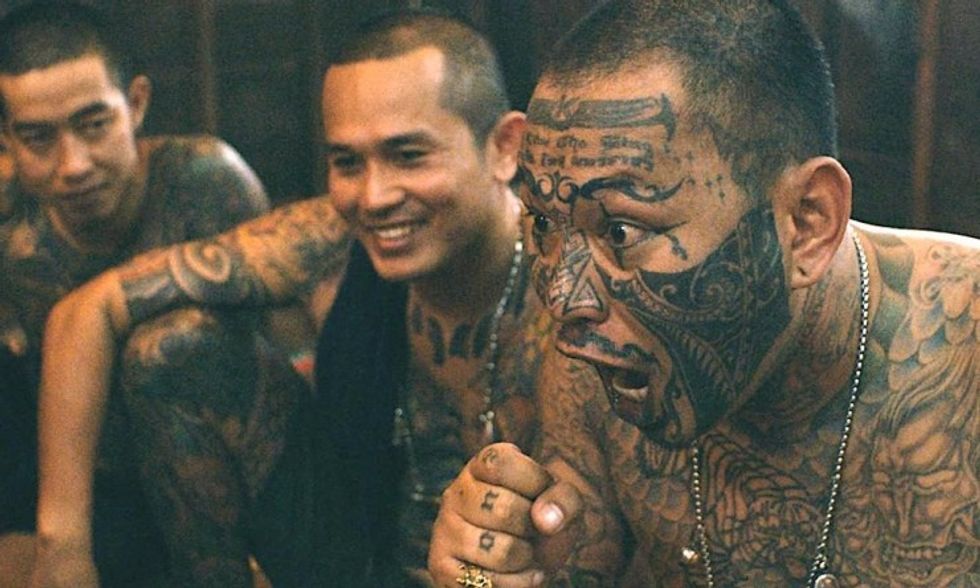

The greatest strength of A Prayer Before Dawnis its immediacy. The film is less like a narrative than a VR experience, following a young raffish boxer named Billy Moore (played with restrained seething energy by Joe Malone) as he is arrested for drug possession in Bangkok, thrown in prison, and forced to find his way out through Muay Thai boxing competitions. To say the camera hugs the characters would be an understatement.

We follow their largest and smallest movements through jail cells, boxing rings, bathrooms, bars, and on the street. Director Jean-Stéphane Sauvaire based the film on a true story and, for added authenticity, filmed the movie in a previously abandoned Thai prison. Many of the extras in the film are actual ex-convicts; the sense that Billy Moore is fighting not just against his opponents but against his very surroundings is rendered extremely viscerally.

No Film School talked to DP David Ungaro, whose many other films include Mary Shelley, Pieces of Me, 99 Francs, and Coco Chanel & Igor Stravinsky, about the challenges of filming so much action in its purest form.

No Film School: What complexities are involved in shooting a film inside a prison?

David Ungaro: The prison we shot in has been decommissioned. It was empty, actually. The art department had to do some work for us to be able to shoot, because it was grown over with trees and plants. It had to be cleaned, rather slowly, but the jail commission was very helpful. We got this one which they were going to destroy as there was already a new one nearby.

NFS: What were the lighting concerns for shooting in this space?

Ungaro: Because the main location was this old prison, we had to redo everything. We referenced tons of pictures from other prisons. The approach was based on doing as much as we could to make it possible to move the camera. So, there was no scene lighting, exactly. Because the camera was always moving, we had to have someone moving with me. 98% of the lighting in the film is practical.

"The key word was immersion. We wanted to be with the character, seeing the sweat, seeing the fear."

NFS: What was your approach to the film's visual style?

Ungaro: There were basically two approaches. There was the dramatic part of the film and then there were the fighting scenes. For the fight scenes, we rehearsed, quite a lot. The director wanted me to shoot it as a one-shot as much as I could. When we started, Joe [Malone] was training, obviously, so we had a coach and a trainer, who was himself a professional fighter.

Also, all of the opponents Joe was fighting were professional fighters. And the thing with those guys is that they’re so precise. They saved my life. Because you know, once you decide you’ll go here, you’ll go there, and then you’ll pull a right punch, and then you’ll go to this side—they do exactly that. They never change. So, there were three big fights that we rehearsed before the shoot and during the shoot on weekends.

For me, on the camera side, the most important thing was knowing where they would fall. When they fall, they can’t control themselves. When they punch, they can always see me. When they fall, if they fall in the wrong spot, they’re going to hit the camera. I was like a dancer—I had to learn the moves. Also, we wanted to be in the ring. We didn’t want to have the camera outside of the ring because we wanted to be as close to the fighters as possible. I’d say 60-70% of the film was shot on a 35 scale and the rest was shot on a 25 scale.

The fighting scenes were all shot with a handheld. I couldn’t get anything else in the ring—it was too dangerous for the fighters. If they hit me, at least I knew I could protect them and push the camera away. When you have a big Steadicam or anything else, it’s metal. It’s too dangerous.

For the nonfighting scenes, the goal was to be as close to the action as we could. The key word was immersion. We wanted to be with the character, seeing the sweat, seeing the fear. A good part of the film was shot with a handheld, and then I also have an exoskeleton. I’m using a French gimbal system called Saab 1, which we used with a midi and a set of high-speed Mach 2s. For the film and its dialogue, we wanted to be really, really close. The gimbal helped me a lot for that purpose and also because we had three professional actors and the rest were real people. We had more a situation than a scene.

We didn’t want to stage too much. We started rehearsing and little by little the director would give them the lines, like, "What happens when you go to a jail and this happens? What do you do, usually?” and then they would start reacting, and the director would say, “Oh, why don’t you do that instead of that?” The director would then give them the line, and at some point during the middle of rehearsal, we started shooting.

Without dubbing or saying “rolling” or anything, they were there, and I was there, sitting and watching. People would go on doing what they were doing and then we would shoot. Usually, the takes were about 10-minutes long, and then we would put in the edits! [laughs]

NFS: For the fighting scenes, did you do a lot of research about fighting? You said you were moving a lot. How did you know how to move?

Ungaro: We looked at boxing films like Rocky and movies by Scorsese, and we looked at Michael Mann’s Ali. We didn’t really like all that, because it was staged, with one punch and a cut, and then another, and a cut, and you feel the tricks and you know it’s a stunt. The director knew that he wanted to avoid that. He’s very committed to that idea: don’t fake anything, make it for real. There was no way that we could have two cameras, so we had to find a way to make it real.

If you see the end of the movie, it’s all one shot: we start from the train, and then we go through the ring, and then upstairs. It’s all one shot! And this one is a real prison with real prisoners.

NFS: Was that less comfortable?

Ungaro: It was interesting. It’s a good jail; the jail director was very helpful. It’s actually the one where Michael Jackson shot his video, you know the one where he’s in jail, and he’s about to be put with 2,000 inmates. The director likes to have fun like this.

It was a real jail, so it wasn’t the same kind of shoot we had in Thailand. In Thailand, we were shooting with real ex-convicts though. They were free, they were out. In the Philippines, it was a closed jail.

NFS: How did you work directly with the actors and follow their lead? There were a lot of tight shots.

Ungaro: You just go for it. I was right on their shoulders, many times. It’s fun and it’s like a dance. I wouldn’t say those guys were just fighting because fighting is random. This is a sport, an art. Muay Thai boxing is like dancing for them. Of course, sometimes we had things not going where we wanted them to go because it’s still a lot of punches. Overall though, it was really interesting because I had to learn and rehearse with the actors and with the camera.

It took us quite a lot of time to rehearse, obviously with the training and the warming up and the running with them. We were happy at the end of each take because everyone was so involved. I had to develop a language with them. If I was blocked at some point, for instance, I would put my leg in between them so that would know I was shooting right between them.

I could then come around and do my 180 and then do the reverse. Sometimes I was holding the camera with only one hand and I would put my hand on the shoulder of the fighter in front of me so that I could feel his moves. I could go back when he was going back. You have that split second to react and then it’s too late and the guy is in already in your face.

"For me, Thailand is like heaven. Everywhere there’s color—it’s chaotic but it’s also like the real Blade Runner."

NFS: Did you have autonomy over what you were doing? Was there a lot of conversations with the director about it?

Ungaro: We had a lot of dialogue. The director stayed in Thailand for a year. That’s the way he likes to work. I know Thailand as well, as I’ve been there many times. We were looking at being as natural as possible using minimal lighting. We had a very tiny budget.

The writer was very good to work with—if we had a scene we couldn’t light but there was another place in the story where we could light it, we moved the scene. If it was daytime and it was too bright, and I couldn’t control it, we changed. Of course, because we had a lot of long long takes, there was a lot of iris. My second AC was putting iris on the camera all the time.

"In the scene in the club, we follow him on the street, then we follow him into the men’s room, then we follow him out, then there’s the drug deal, then he goes out, and then there’s another bar. it’s basically a 10-minute shot."

NFS: What kind of background work did you do before you started shooting?

Ungaro: The prep we did was by going into the real places. We went to Muay Thai boxing evenings, we went to real prisons, we went to strip clubs, etc. to try to get a feel for the real thing. We didn’t take too many pictures because these were not the kind of places where you could just pull out your camera [laughs].

For me, Thailand is like heaven. Everywhere there’s color—it’s chaotic but it’s also like the real Blade Runner. If you go to Bangkok and go down the alleys where there are street vendors, for me, it’s like science fiction. We knew that, number one, we wanted to be able to move the camera. I was willing to sacrifice some lighting just to keep that energy.

In the scene in the club, we follow him on the street, then we follow him into the men’s room, then we follow him out, then there’s the drug deal, then he goes out, and then there’s another bar. it’s basically a 10-minute shot. We liked that space but when the lighting wasn’t okay, we added a practical light. The prison was the same—we had pictures from a prison, so we recreated some of them, and then for the scenes in the cell, I used tungsten fluorescents. The main thing was that the director wanted to be with the character: all the time, all the time, all the time, all the time.c

For more information on 'A Prayer Before Dawn,' click here.