No Film School Reader Wins TIFF Audience Award 2018 and Shares 5 Tips for Film Fundraising

“From the Coen brothers to anyone making their first film, the approach is similar: determine EXACTLY what you require, and no more."

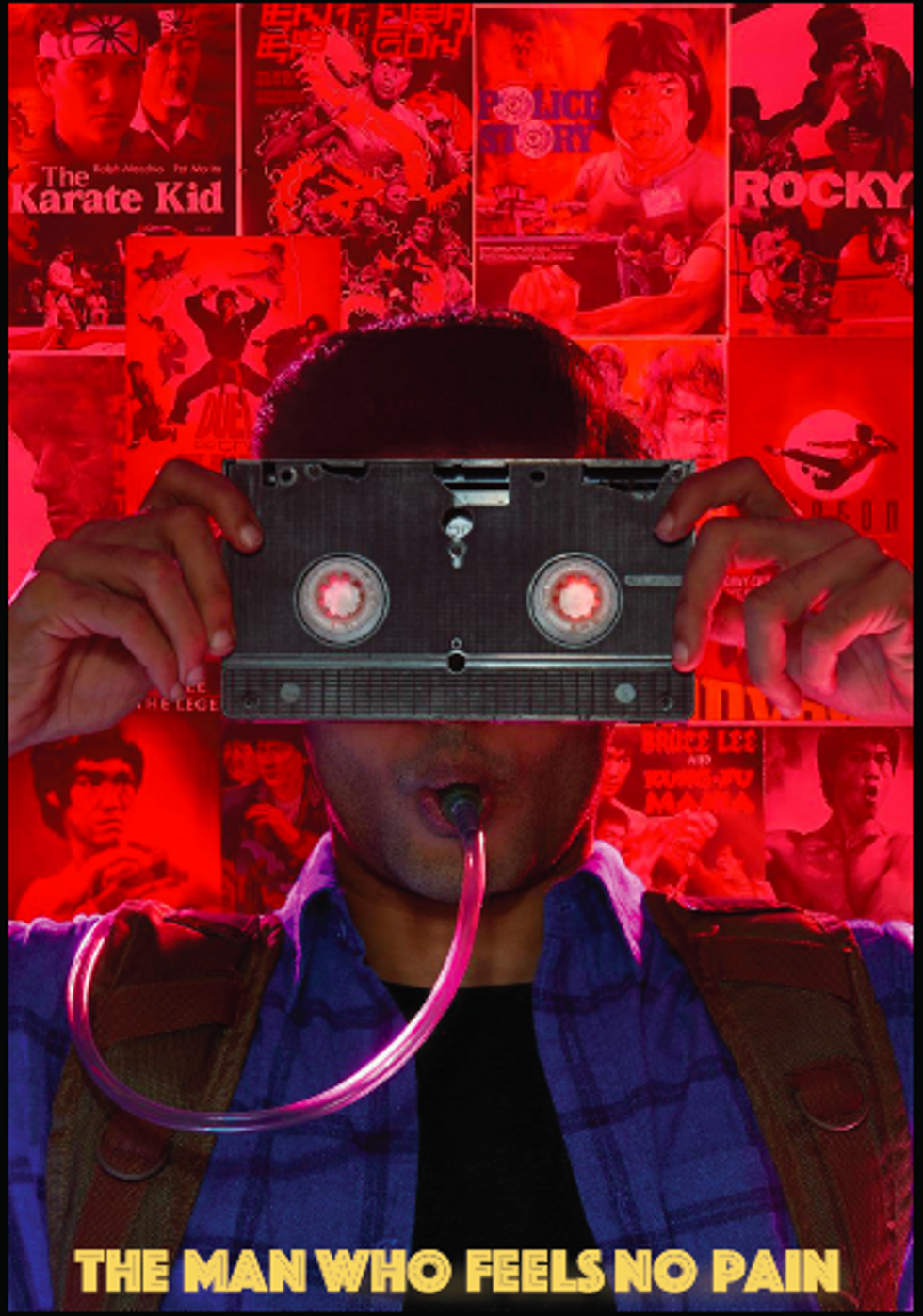

Vasan Bala’s The Man Who Feels No Pain made history twice this past week, the first for being the first Bollywood film to be admitted to the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF)’s Midnight Madness section and, secondly, for being the FIRST Bollywood film to win a TIFF Audience Award. As for the film itself, it’s uproarious.

The Man Who Feels No Pain is like a highlight reel from our favorite action movies of all time. From Enter the Dragon to Big Trouble in Little China to Die Hard, the film is a love letter to all of those unapologetically over-the-top spectacles driven by a pounding heart beneath layers of muscle.

Its style is dialed all the way up to Baby Driver but choreographed to the beat of action classics. Its hero, Kung-Fu flick fanboy Surya (charismatic newcomer Abhimanyu Dassani), was born with congenital insensitivity to pain. “You can Google it later,” one character says in an aside. Using his illness as power, Surya decides to take on 100 fighters. Absurdity ensues. In sum, Bala’s film embodies the same spunk as nine-year-old Bala when he told his parents that he was going to be a filmmaker.

How did this child from Mumbai turn his zaniest dreams into a film that transcends cultures and continents all on his own terms? In part, according to him, he did it by reading No Film School, along with a strong dose of guerrilla-style grassroots filmmaking. No Film School sat down with the gregarious young director to explore his M.O.

1. Be practical

Bala first attended TIFF in 2012 with his performance-driven drug drama, Peddlers (after its premiere at Cannes’ Semaine de la Critique). But even the second time around, Bala describes his festival experience as surreal. “Being at TIFF is very empowering. You get to feel like an artist for a week before returning to reality,” Bala chuckled, "which is cool—I’m cool with one week as an 'artist'—and it replenishes my courage to keep making independent films, rather than trying to design a mainstream product that will actually be funded.”

Bala managed to fund his first feature, Peddlers, via crowdfunding on Facebook. The indie thriller budget was under $100,000, so he developed a pitch aimed at friends and acquaintances. “It wasn’t a messy thing with thousands of separate people donating,” he explained, “but we aimed for the few who could actually afford it.”

Unfortunately—according to Bala—this approach is no longer possible in 2018. “Six years ago, crowdfunding felt genuine: it was a pure call for help in telling a story. Since then, we’ve abused and killed it.” He grimaced, eyes mournful, “The whole process has become too synthetic and well-designed. Now everyone’s plugging their own agendas, manipulating your tear ducts with stories about the story. It’s harder to know when to trust.”

What’s your best bet for getting a film made in 2018? “First, stop playing the victim,” Bala said, giving a hearty laugh. “You shouldn’t go out there with the expectation that the world needs your film. Only you need your film. Once you get past that, try to understand your project’s limitations. And solve them.” Bala clasped his hands, nodding sagely, “From the Coen brothers to anyone making their first film, the approach is similar: determine EXACTLY what you require, and no more. If you’re making an indie film and you want to pay everyone, including yourself—that’s nice, but it becomes difficult. It’s more productive to concentrate funds on equipment and only those things that you need without question.”

Make no mistake: Bala doesn’t want you to be heartless. He demands the opposite. When you can’t be generous with funds, be generous with your spirit. “Don’t treat making an indie film as a business venture,” he urged, “share the credit for whatever comes out of the film with your team. Be generous, but be practical. Realize that a career in indie filmmaking is the exact opposite of a livelihood, at least when you’re starting out.”

2. Let your story do the talking

Great, so now that you’ve gotten over yourself and your financial limitations, you still have a long road ahead. Making your film come to life will require a whole lot of willpower.

Bala's latest triumph celebrates The Man Who Feels No Pain, but—contrary to his film’s title—he admits that filmmaking is painful. He encourages you not to get too jaded.

“Filmmakers are as vulnerable as infants while making their first films,” he laughed. “You’re so consumed by your passion, by your need for funding, that it’s all you can talk about—and that drives people away. You have to let your story speak for itself.” Bala paused, then shrugged, “Obviously if you have a great personality and can walk out of parties with checks from funders, please do that. But if you’re that very self-conscious geek standing off in the corner, don’t worry: you’ll find a way. If you’re really that desperate, you can make it happen. I think we all sort of find a way.”

3. Knock louder

Bala’s own transparency made it clear that, at one point, he too was that geek off in the corner. And if you’re reading this, you’ve surely waded through your own bogs of self-doubt. How do you build the kind of self-confidence required to make your first film? Bala flashed his easy smile, considering what advice he might have given himself a half-dozen years ago: “It’s been an evolution for my personality, definitely. Initially, I had a dire need for a spokesperson,” he admitted with a bashful smile, "and then I realized, you have to speak for yourself, otherwise you’re gonna be in a corner for your whole life, you’ll never move forward.”

As Bala tells it, these doubts are normal and the vulnerability that comes with your first film can work in your favor. Even if you do nothave money, you can use your passion to will your film into existence. You just have to find the sweet spot between humility and self-confidence.

“Every filmmaker out there can play that card during their first film,” Bala insisted. “Enlightenment is being able to return to your initial naïveté, all while learning to knock on doors with a little more confidence each time you do it. The end goal is always the same: you’re not making a film to buy a house, you’re making a film to make your film. No matter how cutthroat the world becomes, there’s always some help right around the corner. Knock a little bit louder. ”

And it will get more cutthroat, Bala warned, as expectations and stakes are raised—but that too is part of the game. “Filmmaking is like a video game,” he continued with an even mix of romanticism and realism, “and your first film is level one, and the stages only get harder and harder after that. Luckily, you evolve too, you get better and better at playing the game.” He paused, “and that’s as it should be. I don’t think such a personal statement should be easy.”

4. Create your own army

For many years, Bala worked as an Assistant Director under directors such as Michael Winterbottom (Summer in Genoa, The Killer Inside Me). As a wannabe filmmaker, he took careful note of what his mentors did on and off set. In particular, he learned the value of teamwork. Just like the action hero assembling his band of rogues for the final battle, Bala recommends a hawk-like vigilance in the search for potential friends and collaborators.

His impish grin flashed again. “Go out and create your own army. Don’t worry about your collaborators’ résumés. If you’re chasing names, it’s never going to be be an equal collaboration—you’ll just be managing egos.” Bala shook his head, insistent, “Don’t look for a babysitter for yourself. You have to be the guy who’s ahead of the curve. The guy who’s discovering unborn talent in a great DP, not hiding behind him or her. The same goes for any collaborator you need.”

Bala lives up to his own advice: he met his own cinematographer Jay Patel while working for another director. “I was shooting on a tracking vehicle with no lights, and I said to this guy, ‘I want this in 48 fps.’” Bala chuckled, shaking his head, “I knew any other DP would have made a face, but this guy, he just switched it on. I watched how he shot it and I was like, ‘I gotta work with this guy!’ When you come from No Film School, you have to rely on your instincts." As it happens, Patel and Bala were both huge fans of Die Hard and their fate was sealed.

Not long after, he found his Action Coordinator on YouTube. “I found these stuntmen from LA who recreate a Jackie Chan-style that I love; I began interacting with them a good three years before I had funding. By the time production began, we were on the same page.” Bala’s sister did costume; a close friend handled art direction. As for post, the film was edited by Bala’s wife. “My daughter was born while the film was being made," Bala revealed, "and my wife was feeding her with one hand and editing with other.” Bala shook his head, still incredulous.

If Bala’s success is proof, mental synergy and on-set relationships are more important than any pedigree. Plus, when you find collaborators instead of babysitters, you learn to take responsibility for your project. Bala gestured emphatically: “As a writer/director, you have to take 100% ownership of the product. And fail, which is fine. Take all the blame for failures, but share credit for success with your team.”

5. Find Common Ground

From the flashback where Surya’s mom fights off a Terminator to the “training montage” spent watching and re-enacting action classics, the driving force behind The Man Who Feels No Pain is a profound love of cinema. More specifically, American cinema, and the pivotal role that it played in Bala’s Indian childhood.

“One of the great equalizers in the world,” Bala explained, “has been the Hollywood export. Hollywood taught me to dream. I was just this middle-class boy growing up in Bombay, and there I was privy to all these characters, all these perspectives, all these cultures. It was empowering. Other countries can claim that Hollywood is a threat to their indigenous film industries, but I think that it has fueled an entire generation of filmmakers. We may resent Hollywood’s capitalism, but there’s reason for gratitude: it has been the catalyst for people the world over to fall in love with film.”

For Bala, Hollywood’s export is a universal language. He cited his experience at Sundance’s 2014 Director’s & Screenwriter’s lab, where he developed The Man Who Feels No Pain alongside other filmmakers including Ana Lily Amapour (The Bad Batch) and ‘The Daniels’ (Swiss Army Man). “We realized that we’d all grown up on the same cinema,” he asserted, “and it’s an outstanding tool for finding common ground.”

Bala has an answer for industry critics: “We don’t have to dethrone the powers,” he insisted, “as evolution is always taking place. We can’t really fight the superhero films, but they’ll be on their way out organically. Instead, we should fight for our own stories, for our own small space on the screen, and our own limited run in the theaters.”

Take Bollywood for example: for many years, it has been oversaturated by “song-and-dance, rom-com escapism—and not the thrilling kind,” Bala added with a laugh. But then, as India’s economy expanded, Bollywood has become more sophisticated and that means better movies.

Bala makes it sound simple: “The guy who was a cart puller 30 years ago now has a son who’s a bank teller. And this son now has his own children, who will go to better schools and have access to Netflix. Tastes are evolving. People have more to aspire to. More and more Hindi filmmakers are trying new, exciting stuff.”

The Man Who Feels No Pain is exhibit A.