Do You Know Who the Antagonist Is in Your Character-Driven Story?

Sometimes, the protagonist is the bad guy of their own story—and that's okay.

For every story that has a conflict, there is an antagonist to push against the main character, challenging their goals to resolve the conflict. Since most stories have a conflict that transforms the protagonist by the end of the narrative, there will almost always be an opposing, antagonistic force that challenges them.

Typically, a story will have a protagonist who has a goal that defines the plot, but there will most likely be an antagonist who shares an interest in the protagonist’s goal and who has different intentions that conflict with the protagonist. The relationship between these characters is an oppositional dynamic that is vital to the conflict of the story.

In stories with external conflict, the antagonist is fairly easy to spot. We have the all-powerful titan Thanos who wants to eliminate half of the world to protect the limited resources. We have Alonzo Harris, who is a crooked detective with a God complex who wants to serve justice in any way possible, or Hans Landa who is the essence of privilege and evil.

But what if the story doesn’t have a clear antagonist?

Can the story still have an antagonistic function to create conflict for the protagonist?

The answer is yes, and the antagonist can be found within the protagonist(s).

What do you do without an antagonist?

Scott Myers from Go Into The Storybelieves that stories that lack a physical antagonist character still have “a [antagonistic] function in the form of an oppositional force standing in the way of each Protagonist’s perspective transformation-journey.”

We can most often see these antagonistic functions that Myers talks about in character-driven films. These are films that focus on characters and their development like(500) Days of Summer and Juno.

In each one of these films, Myers notes that all of the protagonists are “living with their own shadows and the weight of those expectations, that ‘nemesis’ constantly contrasting where they ought to be with the rather mundane and inspired lives they are actually leading.”

Let’s break down what makes these films’ protagonists their antagonists, and how you can write internal conflict that is motivated to be resolved by external events.

(500) Days of Summer and the misreading of The Graduate

In (500) Days of Summer, Tom (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and the root of his antagonistic function are articulated in the screenplay, as the narrator states that Tom believes he will never be happy until the day he meets his “soulmate,” which is a belief that came from “a total misreading of the movie, The Graduate.”

Tom believes that love is the key to happiness, but fails to see the terror in the faces of Ben and Elaine as they sit on the bus and come to the realization of what they just did. His overly-romanticized view of love becomes his internal psychological conflict that is constantly underscored and challenged by his relationship with Summer (Zooey Deschanel)—and his internal conflict is what eventually leads to the death of their relationship.

While Tom thinks Summer is the villain of his story, he fails to realize that his expectations of women and his infantile romanticism are what hold him back from the healthy and fulfilling relationship he desires.

Juno and the mask of adulthood

Another case where the antagonist function is filled by a character’s internal psychological dynamic is Juno.

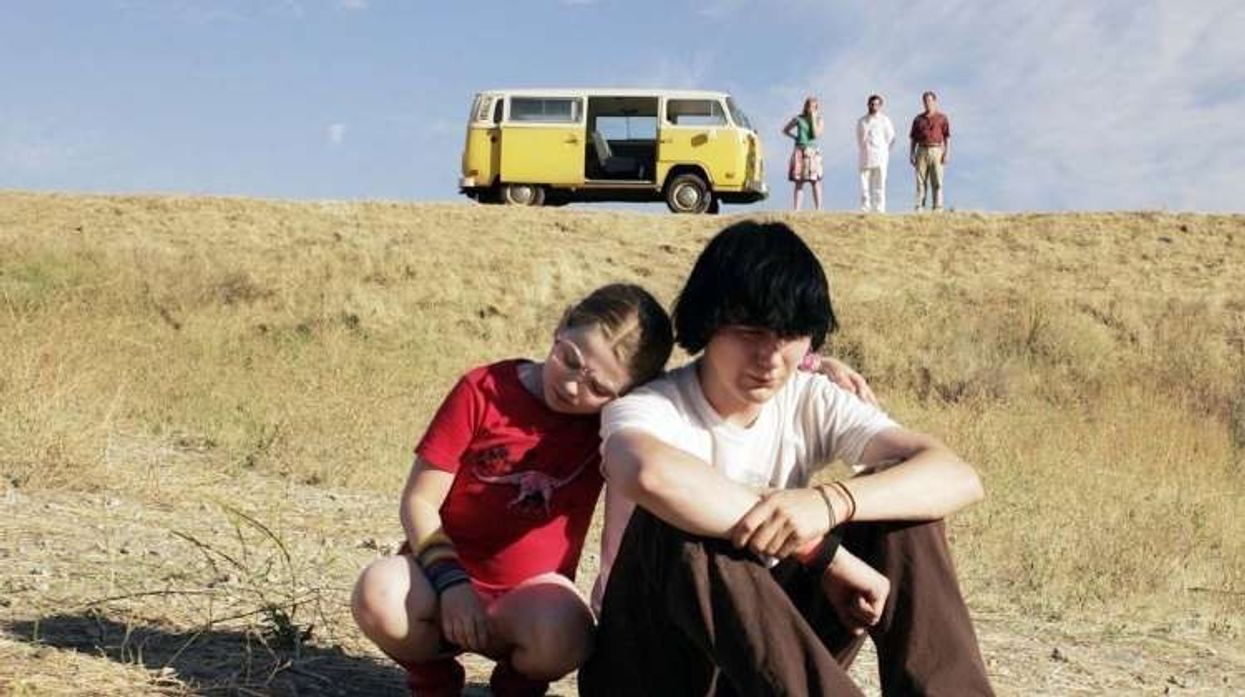

By looking at the two big questions that typically help define the protagonist, Myers finds that Juno (Elliot Page) wants to find her baby a good home while needing to be a teenager. Her internal conflict is shaped by the rejection she felt from her mother. In an attempt to feel some control over her life, Juno has tried her best to jump out of her youth and into adulthood, growing up quickly to avoid the pain of her trauma.

Myers sees that the antagonist of the film is not Mark Loring (Jason Bateman)—an adult who acts like a child—but the mask Juno convinces herself to wear to protect her from her trauma.

Unlike (500) Days of Summer, Juno ends with Juno resolving her internal conflict and ripping away that mask she has been wearing throughout the film. She isn’t trying to be someone who distinguishes herself from her peers. Instead, she acknowledges the pain of her past and allows herself to be a teenage girl who sings a cute duet with Paulie (Michael Cera).

How to write an antagonistic function

While studio executives find comfort in screenplays with a clear protagonist and antagonist characters for many reasons, you can create a great story that doesn’t have a physical antagonist.

A great place to start is by studying romantic comedies and dramas, since stories that fall into those genres are focused on internal struggles that are motivated by external events.

For example, Sally (Meg Ryan) and Harry (Billy Crystal) in When Harry Met Sally constantly challenge each other's ideas of romance until they come to terms that their beliefs about romantic relationships do not guarantee a happy ending. They have opposing ideas that slowly change over time as they get to know each other and establish a relationship that contradicts their initial ideas.

It’s that change in a character’s beliefs that becomes the story’s conflict. Will the protagonist change their ways or view their issues in a new light because of an external force?

That external force can be anything from a meteor on its way to collide with Earth like in Seeking a Friend For the End of the World, or a toy coming to terms that he is not a Space Ranger like in Toy Story. These character-driven stories have external events that influence the direction of the stories, but it’s the character’s internal struggles and desires that force them to react to the external events that motivate the narrative to move towards the climax.

Consider your character and the inner struggles that define them, and then put them through a situation that forces them to look at their internal struggles. Your protagonist’s internal state and their reality must clash to drive the plot forward. How it all ends is up to you.

What is your favorite antagonist from a character-driven story? Let us know in the comments below!

Source: Go Into The Story