Cronenberg's Psycho-Horror 'Possessor' Is a Masterclass in Inventing Practical Effects and Playing with Vintage Lenses

Brandon Cronenberg and DP Karim Hussain spent 7 years developing Possessor, during which they invented a full library of practical effects and a groundbreaking approach to cinematography.

When it comes to the Cronenbergs, the apple doesn't fall far from the tree—especially if that apple is a prosthetic head, and if it smashes into bloody pieces when it hits the ground. Brandon Cronenberg, David Cronenberg's son, has continued in his father's tradition of pioneering sci-fi body-horror. His feature debut, Antiviral, premiered at Cannes in 2012, announcing the younger Cronenberg as an audacious director to watch. Now, 8 years later, Brandon is at Sundance with his sophomore effort, Possessor, in which he considerably ups the ante on gore, violence, psychological chill, and scintillating practical effects. It's a thrilling descent into body-snatching phantasmagoria, with mind-melding visuals and a masterfully created atmosphere.

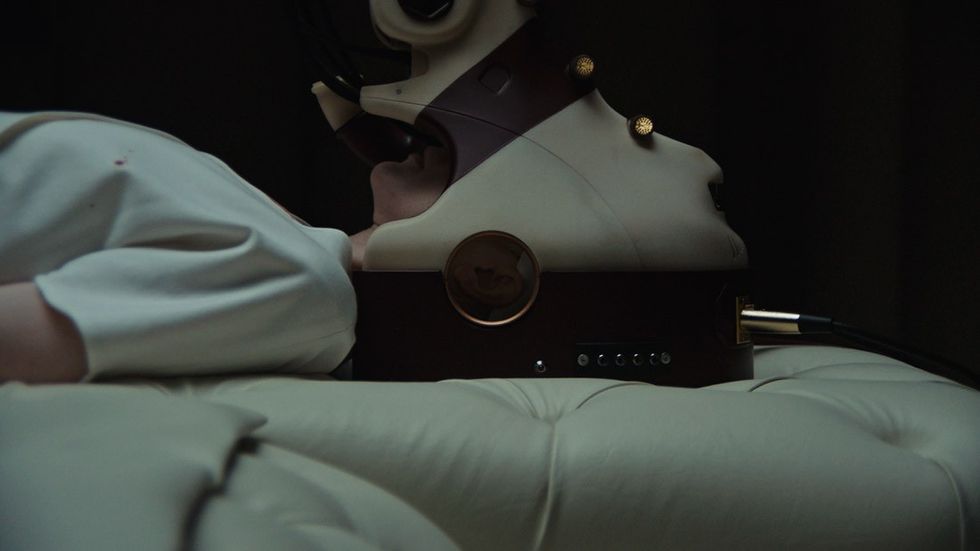

Possessor stars Andrea Riseborough as Vos, a woman who inhabits the minds of others through brain implant technology. As an elite assassin for a secretive corporation, she takes control of victims' bodies in order to force them to commit murders and suicides. The job is mentally taxing, and Vos is fraying at the edges. When her new host, Colin (Christopher Abbot), refuses to fully submit to the physical and psychological takeover, the disembodied assassin and her victim enter into a dangerous tug-of-war that threatens to obliterate them both.

At Sundance, No Film School sat down with Cronenberg and the film's DP, Karim Hussain, to discuss the technological innovations they employed to bring this visually-stunning work of sci-fi horror to life.

"The movie was consistently supposed to go one year, then it died, then came back, and died again."

No Film School: How did you conceptualize the world of this film? It's very complex.

Brandon Cronenberg: I was interested in making a film about how we construct and maintain our identities as people, and the potential disconnects between those identities and our lives. A lot of the film and its world is sort of metaphorical. It's not really meant to be a speculative fiction about where we're going. It's set in an alternate past, actually. The world is designed to be a discussion of the themes rather than creating a realistic future.

NFS: What was the process of world-building like while in the screenwriting phase?

Cronenberg: It was a complicated process because I had way too many ideas. I knew, in a basic way, that I wanted to play with a film where someone could inhabit someone else's body and live their life. Building a world around that partly came through the writing—trying to find a world that was slightly skewed but also familiar.

But a lot of [the world-building] also came through the process of making the film. You get other collaborators involved. You're all working together. You have a sense of what your limitations are and you create the best world through that process.

"The subconscious mind, I believe, reacts differently when something is practical as opposed to a CGI effect."

NFS: It's been eight years since your feature debut, Antiviral. Were you developing Possessor this whole time?

Cronenberg: Yep.

NFS: What took so long?!

Cronenberg: Antiviral was my first film. When it premiered at Cannes, I didn't have another script ready. I tried to put the [momentum] into one script but it was too bloated. I eventually split that into two scripts, and Possessor became one of them.

There was an initial period of writing, finding the film, perfecting the script. And then, as with a lot of indie films, it just took quite a while to get the financing and casting together. It started moving really quickly when we got the right people together. But it's just hard, especially with an independent genre film, to find the right people who want to support it.

NFS: Possessor is, in many ways, defined by the visual communication of complex ideas. Your collaboration with Karim must have been very fruitful. I read that you both "discovered things that no one had ever done in a mainstream movie before" in terms of practical effects. Tell me about this process, including the research, and what it is that you discovered.

Cronenberg: Karim is one of my core collaborators. He shot Antiviral. We lived on the same block for quite a few years. We spent a very long time, because the film took so long, working out camera tricks and effects.

Karim Hussain: As Brandon said, Possessor had an unusually long development period—probably 5-7 years of active development and 4 years during that of prep. The movie was consistently supposed to go one year, then it died, then came back, and died again. So during that time, Brandon and I would get together in my living room—I have a projector and screen—and experiment with ideas and camera techniques. We shot some low-budget music videos where some of the visual ideas in Possessor were birthed.

"We created essentially a library of effects that are completely in-camera."

Cronenberg: We created essentially a library of camera effects that are completely in-camera. Actually, almost all of the scenes involving violence or hallucination are rooted in practical effects.

Hussain: The projection vortex concept came from one music video we did with an artist named Animalia. The concept of filming the subject in front of a screen and projecting a direct feed from the camera you’re filming from onto it has been done before—it gives you a vortex into a kind of infinity as if you were in a small room with mirrors on either side of the walls. But we then added two cameras and two projectors, over-projecting over the same images on one screen. With different lens sizes and shutter angles, it created very interesting effects: delayed movements, flashes of light. Instant, practical, and live super-impositions where you could have faces appear one over the other or flash on and off. Everything is done live, with a separate autonomous camera filming portions of the projections on the screen that are interesting to us. Those shots are what’s used in the final product.

We upped the ante with even more ideas added to the video vortex projections tunnels in Brandon’s short film Please Speak Continuously And Describe Your Experiences As They Come To You, which was in many ways a warm-up and test for Possessor. It was shot about a year before we finally began production on the feature. The projection vortex effects are even more present in the short, as well as many of the other practical color techniques that we applied on the feature.

"When shooting projection effects, it’s really a lot of trial and error with regards to your shutter angle setting and live feed camera settings."

When shooting the screens and these projection effects, it’s really a lot of trial and error with regards to your shutter angle setting and live projection feed camera settings. The most subtle angle or setting change can affect everything. Some techniques you had down perfectly before can suddenly be different the next time you try for no discernible reason. It’s really about feeling it out in an intuitive manner. That said, by the time we got down to doing the Possessor shots using these techniques, we had a pretty good idea of what we were doing.

Cronenberg: We played with old-school video feedback and the coloring of the scenes. For instance, when the scenes are red with yellow flares, those kinds of color effects were all done in-camera. And the image distortion—where there's a kind of bending of the image with yellow flaring—that's all done practically. That came out of our experimentation. Matt Hannon, my editor, did an amazing job mashing together the various effects.

Hussain: Probably the practical effects that required the most research and development were the effects using sound to provide unusual effects that are normally done with CGI. We wanted the movie to feel different and more organic, so we found ways to do them practically, without any CGI enhancement whatsoever.

"Seeing as this effect has only been done in scientific videos or YouTube experiments, we had to learn a few lessons the hard way."

Early in the film, the character of Holly notices a fountain in a hotel lobby where the water appears to hover, frozen in place, in the air, and then move backwards up the spout. Brandon had seen some scientific experimental videos where the illusion of water “freezing” is achieved by having the liquid flow in a tube placed over a subwoofer speaker, where a 24 Hz tone is fed into the speaker. To do this, you must shoot the image at 24fps and tighten up your shutter angle drastically from the regular 180 degrees, which requires, of course, more light. This will give the illusion of the water staying in place and trembling. It’s only visible in-camera. Then, if you change the tone to 25 Hz, it will give the illusion of the water going backward, even if on set it just looks like the water is flowing normally.

Now, seeing as this effect has only been done in scientific videos or YouTube experiments, and never on a mainstream fiction movie with 70 people standing behind the camera, we had to learn a few lessons the hard way.

Firstly, in collaboration with the practical effects department and art department, we built a special fountain that could house a working subwoofer inside of it, where the water would flow over it. This took a lot of trial and error to get it right. Of course, all modern moviemaking is based on wireless signals. The signals to the various monitors are essential—the shots were done on a Steadicam, so the focus puller needed to have an image to focus, and we needed to see if the effect worked. So we needed the radio frequencies to work. But the movie was shot at 24fps, and we discovered that sending off a massive, loud, 24 Hz audio signal into the air completely kills any 24 Hz wireless video transmission, so the poor focus puller was freaking out wondering why all the wireless video would die the instant we started a take. We ended up hard-wiring everything, and it was just the next day, after a night’s sleep, that I figured out what happened.

So, if you want to sabotage a modern film shoot, fire off a loud 24 Hz low-frequency tone in the air, and none of their monitors will work wirelessly!

Hussain: Another interesting effect using sound was the technique of acoustic levitation. Again, Brandon saw examples of this in scientific videos, but none of this had been attempted in a mainstream movie. So with the practical effects department, a small acoustic levitator was created, which is essentially two small opposing platforms with a small space between them, and a bunch of tiny speakers placed on each platform, throwing enough sound waves from one side to the other to be able to levitate small objects or liquids in the center of the sound throttling. Again, it was lots of trial and error to get it right. We settled on a small, lightweight particle that floated successfully. This is the strange object that Colin sees when his control breaks down, floating in the air, that he touches. It moves in a way that CGI wouldn’t be able to do—it feels more organic and chaotic. The subconscious mind, I believe, reacts differently when something is practical as opposed to a CGI effect.

"This was a practical effect done live with a DSLR camera with terrible rolling shutter defects on it."

Another effect we did was when Colin breaks down and he sees what looks like the blades of an office fan melting and deforming. This was a practical effect done live with a DSLR camera with terrible rolling shutter defects on it, the Sony A7S II, and adjusting the shutter speed of the camera so that it kind of synchronizes with the fan blades.

You see this kind of anomaly with your smartphone videos sometimes when you shoot plane propellers. We like to take inspiration from one thing and build it into something else that is new, which of course requires experimentation. This shot, like many other shots when the control on the host body breaks down, were re-photographed in post with the rushes projected in my living room on a screen. We re-shot with a lens baby and Brandon flaring the glass with a yellow flashlight live.

These shots perhaps could have been done digitally, but they wouldn’t have felt as organic and dreamy as they do currently, and I believe they work because we did them live and practically, with all the imperfections that come with that. Humanity is imperfect, so we instinctively feel different when we see practical images, with their subtle lack of perfection.

NFS: Tell me about the practical effects you developed for the prosthetics on the film.

Cronenberg: We were very lucky to get Dan Martin, our VFX artist. I don't know if you know his work, but he's done amazing, amazing stuff. Like Karim, he's a very innovative guy who has a wealth of ideas he wants to explore. So he slotted in beautifully with our team and we all worked together to create those images.

"Dan's fake heads are spectacular. They're really, really shockingly good."

He did a lot of work in terms of practical violence—fake heads and that kind of thing. Dan's fake heads are spectacular. They're really, really shockingly good. There are shots that keep confusing audiences—people ask me how we achieved them. For instance, there's a scene shot in close-up with a knife going into a neck. The answer is that Dan just does these things really well. We could shoot extremely close up to his work. We could use a probe lens for the closeups in the hair. Dan also built us great wax figures. All of that melting stuff is practical in the hallucination sequences.

NFS: Karim, how did you approach shooting the prosthetics?

Hussain: Like with shooting any prosthetics, you have to be careful with the lighting. You have to make sure your lighting axis doesn’t expose unwanted seam lines or show reflections on the prosthetics in unflattering ways. You can strategically place a shadow to hide unwanted creases, for example.

Of course, it helps if the prosthetics are as amazing as the ones that Dan Martin and his team provided for us. We shot with a Laowa 24mm Macro Probe up close on some of his dummy heads, with a tremendous amount of light on them and the lens merely millimeters away from the prosthetics. They held up amazingly. He’s a wizard with silicone and also with wax, it turns out, as there’s a sequence of heads melting that were made of wax, and they held up great even to close-up scrutiny.

People are reacting quite strongly to the violence in the film. It doesn’t feel like the usual CGI blood and gore you see in most movies today. I think that’s because everything was done practically. The blood was all on set.

Also, the best friend of a prosthetic, besides the DP, is the editor. And Matt Hannam cut the effects brilliantly. Brandon has experience in Make-Up FX, so he knows the techniques as well.

"The Amira seemed like the right choice, and it’s sturdy as hell."

NFS: Speaking of gear, which camera and lenses did you use on which sequences?

Hussain: We shot the movie on two ARRI Amira cameras. We made that choice principally due to ARRI's sturdier body. You can place more accessories on it than a Mini. Also, it has internal NDs, so it's easier to mount batteries. It’s still a light camera, so for the many Steadicam shots operated by our brilliant A Op Yoann Malnati, the weight wasn’t so much an issue. We didn’t need a 4:3 gate or ARRI Raw, so the Amira seemed like the right choice, and it’s sturdy as hell.

We shot principally at 2K ProRes 4444 and some 3.2K ProRes 4444 here and there, if the lenses allowed, and the wider gate made sense for more field of view. Early in the process at Technicolor with Jim Fleming, our colorist, we shot tests of all the various formats that the Alexa Mini and ARRI Amira provided, including ARRI Raw, and blew the images up to 4K and looked at them on a big screen. Our workflow on Possessor was that we would deliver a 4K finished product, but we wanted to see what would be the best formula to get an image feeling closest to older 35mm film.

"Our workflow on Possessor was that we would deliver a 4K finished product, but we wanted to see what would be the best formula to get an image feeling closest to older 35mm film."

After studying the results, we felt that 2K ProRes 4444, not XQ, felt softer and took off the digital edge. Shooting principally at 1280 ISO felt the best for the look we wanted. Some 3.2K, as long as it wasn’t ProRes XQ, was acceptable within the world. We weren’t forced to originate at 4K, only deliver at that resolution, something you can do less and less of these days, so thankfully we could stick to our original plan.

The movie’s final aspect ratio is 1:78, so that simplified things. The theatrical version is even pillar boxed to 1:78 within the Flat 1:85 DCP frame.

Hussain: For the lenses, we wanted lenses that would feel dreamy and soft, without the necessity of diffusion, which is not really Brandon’s thing. So we decided, after much testing, on vintage Canon K35 primes, usually wide open, as our principal prime lenses. Their unique bokeh—which resembles the stump of a cut tree—and softness and shallow depth of field were exactly what we needed. Their older housings drove our focus puller nuts occasionally, though. The most used lens in this set was the 35mm, which just so happened to have the most capricious housing. But that’s life.

On B Camera, operated by Brett Hurd, we used a personal lens I own which is a vintage, 1970’s-era original Angenieux 25-250 zoom. When I bought the lens on eBay, I discovered it had a considerable amount of fungus growing in its rear element, but the effect this fungus gave was beautiful—the unique, dreamy look the fungus gives, alongside its heavy breathing.

"A 90mm Macro Kilar lens fell off the shelf of a film school decades ago from an enterprising employee and has been a staple of the movies I make ever since."

We also used a 90mm Macro Kilar lens, probably from the '60s. It was adapted to PL mount, but that’s the most modernization it has. It fell off the shelf of a film school decades ago from an enterprising employee and has been a staple of the movies I make ever since. It gives a dreamy, auto-diffused macro shot and is also Full Fame. It looks like nothing else. It's very difficult to focus, though. I frequently take the camera myself to do these shots as we’ve developed a relationship over the years and it’s a tricky one to use.

The only modern lens on set was the amazing Laowa 24mm Macro Probe, used on some face and eye shots, and on the prosthetic head inserts where objects pierce skulls, and for some cloud tank work. It’s a stunning, innovative lens that can do things that no other lens can. Also, it's waterproof to an extent. We reduced the contrast on those shots in the grade to make it fit into the movie’s overall look, as it’s a very sharp lens.

Other shots were done on a very old Helios 44 lens, a 13 Blade Iris silver-housed one that had Made In The USSR imprinted on it, to give an idea of its age. Its swirly bokeh and soft contrast are incredibly beautiful. For one sequence when Colin is fleeing down a city sidewalk, I modified a separate Helios 44 lens by inverting the front and rear element, which created crazy blur and bokeh effects.

A 55mm Lens Baby Muse was also used in post-production, but only to re-photograph projected rushes live in my living room, with pressure effects and colored flares shined into it.

NFS: Brandon, do you think that you grew as a director making this film, given that it's your sophomore feature?

Cronenberg: I like to think so. I mean, ultimately, it's hard to have that kind of perspective on yourself. After the smoke clears, people can tell me if it was a better film [than Antivirus]. But I like to think that I was approaching it with a bit of a bigger toolkit, given that the development took so long.

NFS: Do you think it helped that you had so long in development?

Cronenberg: It definitely helped, ultimately, to have had so much time. I wouldn't have chosen to wait eight years to make another film, but given that we did, we went into it with a lot of meticulously planned shoot days. Once everything got moving and we got into the shoot, everyone was very supportive and I didn't have to make any sacrifices. Even in post-production, everyone was weirdly on the same track. So, from a filmmaking perspective, it was all very easy. There was no fighting. It was kind of a wonderful experience. It was more the years of getting to that point that was difficult.

"Brandon is a very practical director. Our ideas can be as wild as possible and the movies can be completely insane, but from a production standpoint, we are very level-headed."

Hussain: Because of all the years of prep and anticipation, once we hit the floor, Possessor was pure joy. It was proof that you don’t need a tense and troubled ambiance on set to make a good movie. This one was the smoothest, tightest shoot I have ever had.

It also helps to work with friends, which is the best way to do it, in my opinion. Rob Cotterill, our 1st AD and Supervising Producer is a very old friend and genre fan with whom Brandon and I have a clear understanding and close relationship. Our producers at Rhombus and Rook Films were nothing but supportive and also, old friends, so that yet again helps.

"A lot of young filmmakers are cinephiles and incredibly film-literate...but if you only draw from film, then you're just doing what's been done before."

It was really a dream shoot, despite the usual challenges that come up on a daily basis. We were just so happy to be actually shooting the movie that the usual troubles and stresses didn’t really faze us. As a collective team, Brandon, Rob, and I don’t like to mess around—we move fast and our days aren’t very long. We know what we want and we always take on challenges that we know we can achieve within our financial means and timeline. Brandon is a very practical director. Our ideas can be as wild as possible and the movies can be completely insane, but from a production standpoint, we are very level-headed and professional. We understand how to get the most bang for our buck, how to stick to our schedule and adapt to do so. And to have a respectful atmosphere on set, which is also important for us.

NFS: Do you have any advice for an up-and-coming sci-fi or genre filmmaker?

Cronenberg: It's hard to give advice to aspiring filmmakers because there's no right way to do it. I think you have to have a sense of yourself and what you want to do. It's hard to talk about because everybody's different and everyone's context is different.

My only piece of advice is to really embrace whatever is available to you and do something that you can achieve very well with whatever resources you have in whatever situation you're in. And make it your own thing. Don't try to do a space epic when you don't have the resources to do it. Don't try to be even another filmmaker. A lot of young filmmakers are cinephiles and incredibly film literate, and that's fantastic, but if you only draw from film, then there's a danger there because you're just doing what's been done before. I think it's important as a filmmaker to have a range of interests and to draw from your own life.

For more, see our ongoing list of coverage of the 2020 Sundance Film Festival.

No Film School's podcast and editorial coverage of the 2020 Sundance Film Festival is sponsored by SmallHD: real-time confidence for creatives and by RØDE Microphones – The Choice of Today’s Creative Generation