Your Guide to Key Lights in Film and TV

Do you need high key lighting or low key lighting for your scene?

'Mank' behind the scenes

In the world of filmmaking and television production, lighting plays a pivotal role in setting the mood, enhancing the story, and captivating the audience's attention.

One of the most fundamental elements of lighting is the key light, which serves as the primary source of illumination for a subject.

In today's article, we will delve into the definition, functions, and examples of key lights, exploring how they shape the visual narrative in both film and television.

So, let's learn key lighting together.

Lighting 101: Intro to Light Placementwww.youtube.com

Key Lighting Definition

The key light is the primary light source that illuminates the main subject in a scene. It creates depth, defines features, and establishes the visual hierarchy within a shot.

The key light's position, intensity, and angle significantly impact the mood and tone of a scene.

Key Lighting Examples in Film and TV

High key lighting in 'Harry Potter'

Credit: Warner Bros.

There are several different kinds of key lighting we should go over. The first two are the main kinds of key lighting that people will reference.

- High Key Lighting: This technique involves using a bright and even key light to minimize shadows.

- Low Key Lighting: This technique uses a key light at a sharper angle to create strong shadows, adding mystery and tension to the scene.

High Key Lighting vs. Low Key Lighting

There are two contrasting lighting techniques known as high key lighting and low key lighting. They stand out for their different approaches to illuminating subjects.

High key lighting is a style of lighting for film, television, or photography that reduces the lighting ratio in the scene. In the early days of film, this was done to deal with high contrast, but now it's used by filmmakers to adjust the mood and tone of a scene.

It's commonly seen in comedies, sitcoms, and lighter genres where a cheerful and upbeat atmosphere is desired, or ethereal.

The definition of low key lighting is a filmic lighting style that uses a hard source to encase your scene in shadow. Low key lighting wants contrast and blackness. It is used in genres such as film noir, thriller, or horror,

Other Kinds of Key Lights

'Fight Club'

Credit: 20th Century Fox

Aside from the main two, there are a couple other ways key lighting is used onf film and TV sets.

- Rembrandt Lighting: Named after the famous painter, this technique involves placing the key light at a 45-degree angle to the subject, creating a distinct triangular highlight on the cheek opposite the light source. It's a classic approach that adds depth and drama.

- Split Lighting: In this setup, the key light is positioned directly to one side of the subject's face. This divides the face into two halves—one in light and the other in shadow—emphasizing contrasts and revealing both strong and soft features.

What Should You Consider When Using Key Lighting?

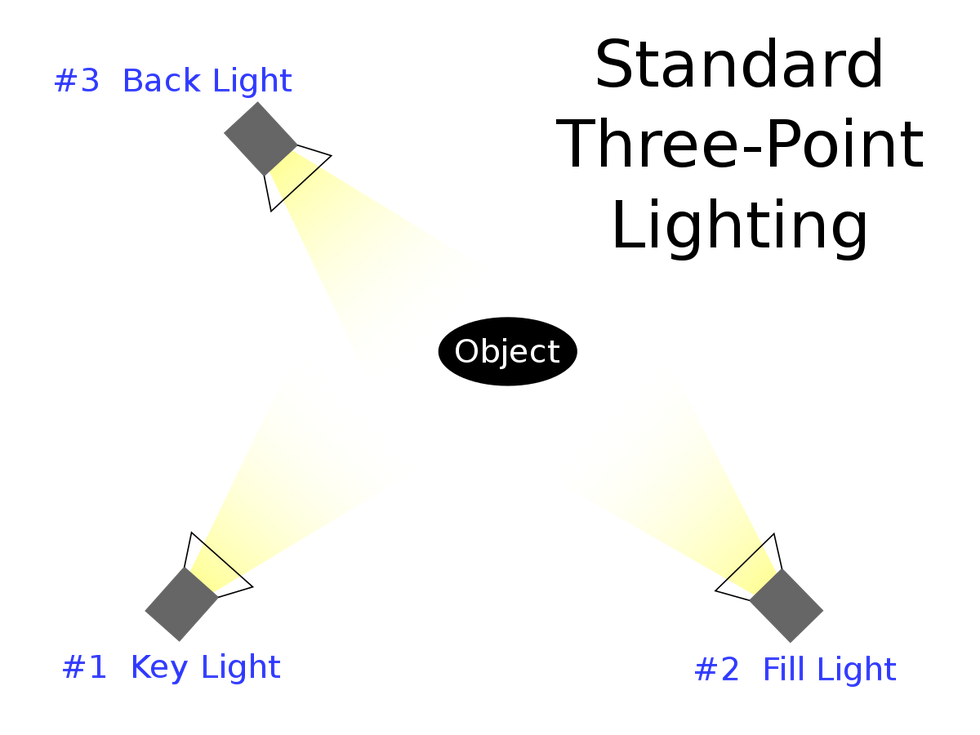

three pointing lighting

Credit: Wikipedia

So you want yo use a key light? Well, here's a few things to take into account before calling "action."

- Placement: Experiment with different angles to determine the most flattering and suitable look for your scene. Higher angles can minimize imperfections, while lower angles can add intensity.

- Light Modifiers: Using diffusers or softboxes with your key light can help create a softer and more pleasing illumination. Reflectors can also be used to bounce some of the key light's intensity onto the opposite side of the subject, filling in shadows.

- Intensity Control: Adjust the intensity of the key light to maintain the desired balance between the key light and other sources, such as fill lights and backlights, to achieve the desired visual effect.

Understanding the role and importance of key lights in filmmaking and television production is crucial for crafting visually engaging and emotionally impactful content.

By mastering key light techniques and their applications, filmmakers and cinematographers can shape the way viewers perceive characters, emotions, and stories on screen, ultimately elevating the storytelling experience to new heights.

Now go get lighting.

- How to Master the Three-Point Lighting Setup and Lighting Techniques ›

- Types of Film Lights (and How to Use Them) ›

- 13 Film Lighting Techniques Every Filmmaker Should Know ›