Why 'Scream' Has One of Best Final Girls In Horror Movies

While the sequel are hit and miss, you can learn a lot from how the Scream franchise scripts treats their lead character, Sydney Prescott -- one of the few Final Girls to have an arc in horror movies.

In 1992, professor and writer Carol Clover released Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, a feminist text that analyzed the recent slate of slasher films. It’s in this text that Clover described The Final Girl, usually a virtuous woman who -- thanks to her upstanding morals and plucky ingenuity -- will outsmart the marauding killer and make it out alive.

“She alone looks death in the face, but she alone also finds the strength either to stay the killer long enough to be rescued, or to kill him herself,” Clover wrote. “But in either case, from 1974 on, the survivor figure has been female.” In the years since Clover’s book was released, the term has been appropriated by the mainstream, inspiring everything from Quentin Tarantino’s underrated slasher-on-wheels Death Proof to The Final Girls, a winking, feature-length deconstruction of the concept by director Todd Strauss-Schulson (if you haven’t seen it, you really should). The Final Girl is now a pop culture touchstone.

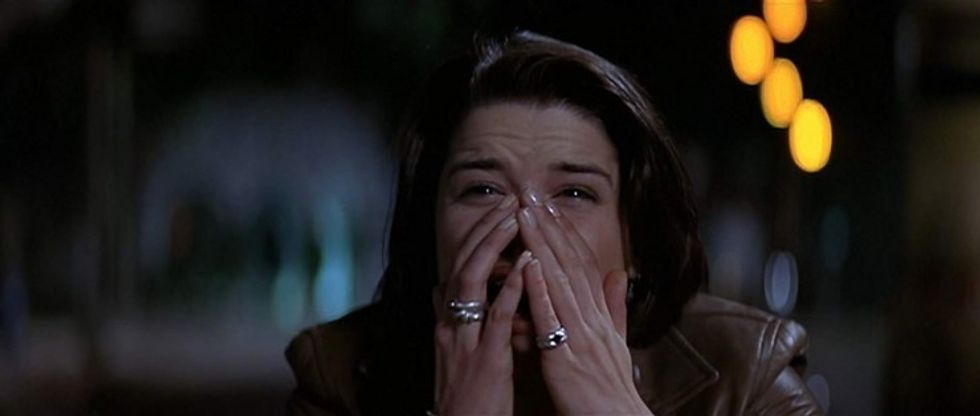

And it’s worth noting that just a few years after Clover’s book was published, the world was introduced to Sidney Prescott (played, flawlessly, by Neve Campbell), who would go on to become the Final Girl of the Clinton Years (and beyond). Or, as this tweet dubs her, “The Survivor Queen.” How she managed to hold this title is just as interesting as any one of her blood-soaked adventures, with just as many twists and turns.

The story of how screenwriter Kevin Williamson came up with the script for Scream (then dubbed Scary Movie) is downright legendary: Williamson, struggling to make ends meet, sequestered himself in a Palm Springs hotel room and over the course of a few days, in a fit of John Hughes-style creativity, cranked out the screenplay. The script was unlike anything that had come before it -- a meta horror movie sprinkled with comedy, that was as interested in the movies that came before it as it was scaring the audience silly. A bidding war followed and the film was eventually made by genre legend Wes Craven at Dimension.

But what’s kind of staggering is that, as pointed out by video essayist Mickey Neumann, Sidney doesn’t really have much of an arc in the first movie. Her mother has been killed (by one of the killers that is now stalking her), she’s a high school student, she’s somewhat reluctant to engage with her boyfriend physically and … she has a nice house? It’s hard to pinpoint in the first film who Sidney Prescott is, exactly, and -- as such -- her arc doesn’t feel as fully realized as it could have been. Yes, she sleeps with her boyfriend (violating one of Jamie Kennedy’s Randy’s rules for surviving a scary movie and one of the tenants of the Final Girl) and winds up uncovering a mystery and defeating the killers. And thanks to Campbell’s performance (and the snappiness of Williamson’s script), you’re able to find nuance and depth where there isn’t much. But over the course of the sequels (which are of intermittent quality), Sidney's character found herself arcing away from victim and toward being an active, triumphant survivor.

Let us pause quickly to flashback to the sale of Williamson’s script. Along with the completed draft of the first film, there were detailed, five-page outlines for two subsequent films. Williamson didn’t envision Sidney’s arc to merely play out over a single film; it was supposed to unfold over a series of a films. This doesn’t excuse the shallowness of the character in the original film, but it does show how you can give additional depth to a character if you have some idea of where they’re headed (especially if you allot for sequels, a staple of the franchise since the Universal Monster films of the 1940’s).

She begins to have a relationship with Cotton Weary (played by a young Liev Schrieber), who was falsely accused and imprisoned following her mother’s death. And maybe, most pivotally, she takes a film class. The knowingness of the first movie, exemplified by Randy, has now become a blanket level of self-awareness. When one of the killers is revealed to be the mother of the first’s film’s baddie, it’s both a logical story-point and something of a foregone conclusion, since Sidney now understands the mechanics of horror movies (and has probably seen Friday the 13th). Williamson’s writing became more sophisticated here and, in turn, Sidney Prescott became a much more interesting character.

For Scream 3, Williamson was replaced by Ehren Kruger, who would go on to script three of the Transformers films. Elements of Williamson’s outline would make their way into Scream 3 and his TV show, The Following. Tonally wonky, it’s the least successful entry in the franchise, a sequel somewhat handicapped by the fact that it opened soon after the Columbine school shootings, when Hollywood’s sensitivity to violence was at an all-time high.

Still, Sidney Prescott takes a fascinating turn in this installment; she’s become a recluse and an operator at a women’s abuse hotline -- which is a great character detail that, sadly, doesn't get more than surface attention. She’s drawn back into the mystery, however, and in the movie’s best sequence, she’s chased through Hollywood soundstages full of sets designed after locations from the previous movies. When the killer is revealed to be Sidney’s half-brother from her mother’s time in Hollywood, he blames Sidney for the entire rash of murders.

But Sidney doesn’t buy it.

She knows that it’s all his fault, stands up for herself, and takes a bullet for it. She knows who she is and she’s not going to let some madman tell her different. At the end of the movie Sidney returns to her home but she is no longer plagued by the fear and anxiety; no longer a recluse, she’s ready to let the world in (again).

More than ten years after Scream 3, Scream 4 finally saw the light of day. Again, production woes beset the project (most notably Williamson getting replaced by Kruger at a late stage), but it still remains a fascinating epilogue for the trilogy. At this point, Sidney has written a book about her terror-filled life called Out of Darkness. But instead of a quick cash-grab, it feels like something that is meant to be cathartic and to encourage those who read it to share their experiences. (Just like her job on the call line.)

One of the stops on her book tour happens to be her hometown of Woodsboro and, wouldn’t you know it, a string of grisly murders has started up again. Evidence in Sidney’s car suggests she could be a suspect and so she sticks around. You can tell that Williamson and Craven were excited to dig into social media, cell phones, and the remake-hungry atmosphere of horror movies at that time. The motivation for one of the killers (Sidney’s cousin) is fame, an appropriately millennium obsession. And throughout this entire ordeal, Sidney knows who she is. She’s back in her home town, defending it once again, and tired of the whippersnappers trying to take her place.

The best, and most well-known line of the movie is when, vanquishing the killer, that the first rule of remakes is to not “fuck with the original.” She is the original. And she is the Survivor Queen.

What is your favorite Scream movie and why? Is there a more well-written scream queen? Sound off in the comments!