This Is the Untold Story of the First Woman Director

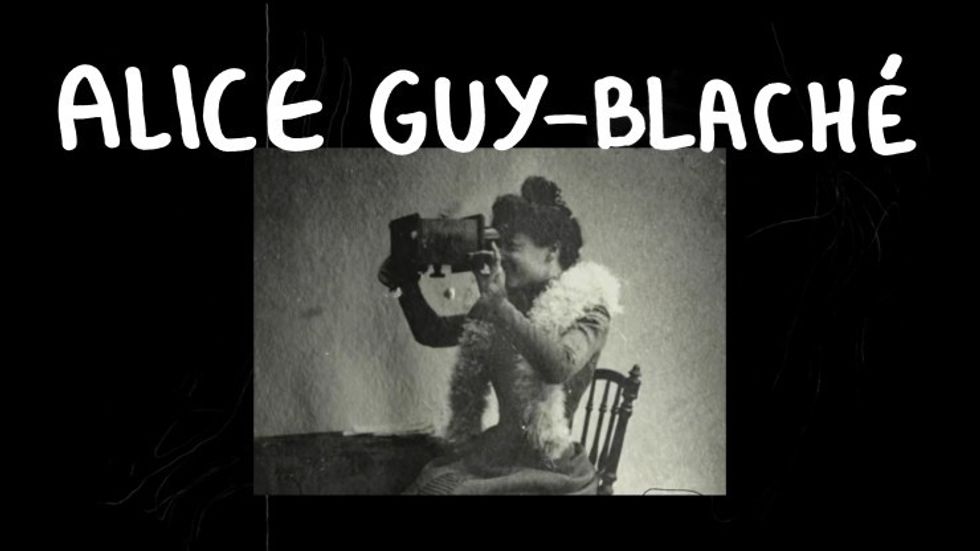

Alice Guy-Blaché was the first woman filmmaker, a visionary, and a true pioneer of the early days of cinema.

From directing one of the earliest narrative films back in 1896 to experimenting with visual effects, color, and sound, Alice Guy-Blaché’s story is just as incredible as her achievements.

Check out the video below to get the full picture, and let’s dive right into it.

When the pictures started moving

In a lot of ways, Alice Guy-Blaché was at the right place at the right time.

In 1895 she had just started working as a secretary for the French inventor and engineer Léon Gaumont. It was an exciting time of innovation, and motion pictures, although very basic, were showing signs of being the next big thing.

Knowing that manufacturers from all over the world, including Gaumont, were competing with each other to create the best version of a motion picture camera, and perhaps even more importantly, a reliable way for the images to be projected on a big screen.

The ones who did it first were the Lumière brothers, and on December 28, 1895, they would make history by conducting the first public screening of motion pictures for a paying audience.

Unsurprisingly, this new attraction was a massive hit, and not before long Léon Gaumont would begin to manufacture his own camera system as well.

Alice Guy-Blaché and the birth of narrative

The main purpose of films in those early days was to essentially document everyday life. They were called actualities, and were nothing more than just a simple shot of something mundane happening—a train arriving at a station, workers leaving a factory, a city street... you get the idea. They were essentially seen as a scientific and documentation tool.

To Alice Guy Blaché however, the potential was far beyond just that.

Being the daughter of a bookseller, she had been surrounded by books her entire life. So one day, as she puts it, she gathered some courage and asked Gaumont if she could try to film a scene on her own—a fictional one. Just like in the books she had been reading growing up.

Apparently, he told her that it seems like a silly thing to do, but as long as it wouldn’t interfere with her regular job as a secretary, she could go ahead and give it a try.

And so she did.

She grabbed some friends and a camera, and the result was The Cabbage Fairy (1896), a simple story about a young couple who wants to have a baby.

The film turned out to be a huge success, and Léon Gaumont was so pleased with it that he decided to enter the movie-making business. To help him with that he appointed Alice Guy as the Head of Production, making her one of the earliest prominent figures in this completely new industry.

Alice Guy-Blaché as a director

Over the following decade, as a writer and director, she was involved in the making of hundreds of movies for the company, and at the same time as the head of production—she supervised the entirety of the film output.

It wasn’t just a fancy title either. Whe was actually involved in every single stage of the process, from personally hiring and training new directors, to managing set designers, scouting locations, finding props, and even making some of the costumes herself.

In 1900 she won her first award for her work, and by 1905 she had directed more than 100 movies using the chronophone—a system that Gaumont had developed for synchronizing picture with sound.

In addition to that, she was among some of the first directors to experiment with a variety of filmmaking techniques—from visual effects to close-ups, reverse speed, and hand-tinted color to name a few.

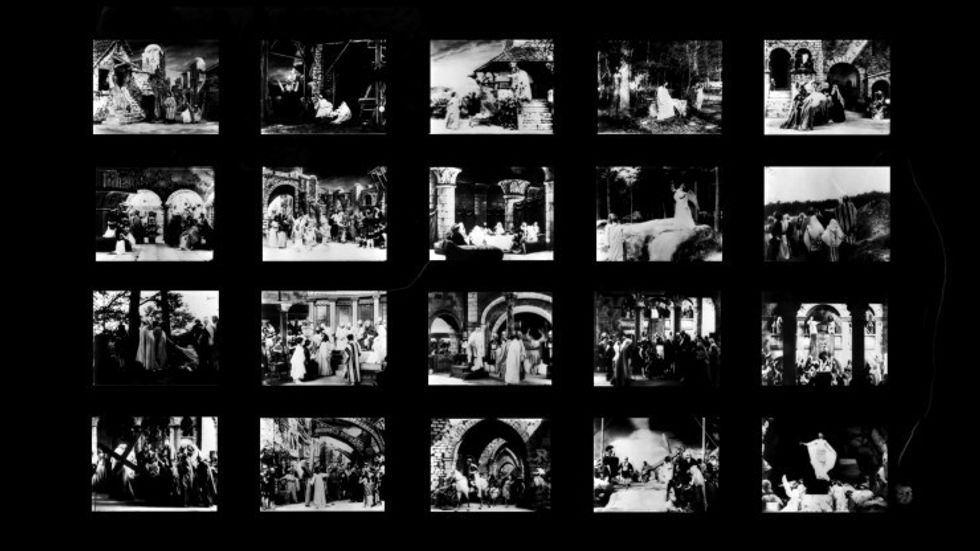

In 1906 after continuous success, she took on her biggest project to date—a 25-part film about the life and passion of Christ.

By all means, it was going to be a challenge. A massive production, big budget, multiple locations, over 300 extras, special effects, and many advanced storytelling techniques.

But if anyone could make it happen, it was going to be her. Once again, it was successful. And when it was projected at the “Society for the Development of the National Industry” in Paris, each scene was met with enthusiastic applause from the audience.

The Solax years

The next chapter of her life takes her to the United States.

She had just married, and moved across the ocean with her husband Herbert Blaché, a production manager for Gaumont whose job over there was to promote the chronophone in that region.

Unfortunately, this venture failed, and the studio Gaumont had built for that purpose was getting underutilized, but what Alice Guy-Blaché saw was opportunity.

So, she rented a part of it and started making films on her own under the umbrella of the Solax Company—making her the first woman to be running a studio.

It was a joint business venture with her husband, and while he was taking care of the production side of things, she was the one directing the films.

Within two years Solax became a major player in the industry, and as the demand was increasing, Alice Guy-Blaché invested in a state-of-the-art studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, right next to Universal and the rest of the American film giants.

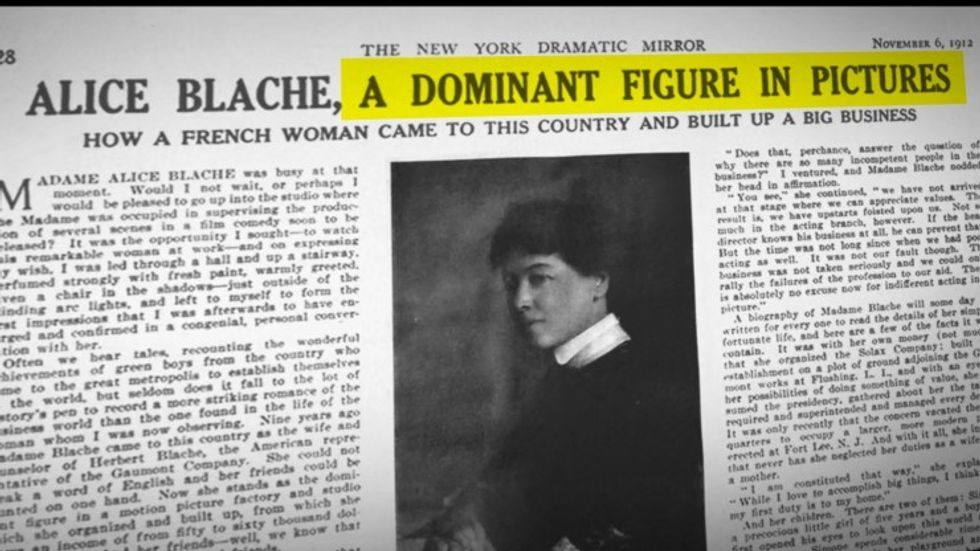

Newspapers were widely reporting on her success, calling her a dominant figure in the motion picture industry. But even though she was now a businesswoman, she was always a film director first. She kept on improving her storytelling skills and there were a lot of things that made her movies special.

For one, they were about life. The acting was a lot less theatrical than the norm at the time. She focused on real human emotions and that was so important to her that she had a sign in her studio that read “Be Natural”—as that is all she wanted from her actors.

But what's even more is that she was willing to go against the grain. She had women play important and empowering characters. She was the first one to have an all-African-American cast. From gender inequality to antisemitism and human rights, her movies challenged social norms—and her female perspective was not only present, but very much needed.

Erased by history

So, considering how important she is for cinema, the main question remains—why was she largely forgotten?

The answer is complicated, but the obvious place to start would be 1914.

A war had broken out in Europe and with it came a lot of uncertainty and economic downturn.

On top of that, back in the States, Thomas Edison had just created a trust, which meant that all film studios that were not a part of it had to pay some hefty licensing fees. This is actually one of the main reasons why many of them eventually moved from the East Coast to California.

Seeing that the future is in Hollywood, Herbert Blaché leaves his wife and moves over there with his mistress—an actress they had worked with for years.

Alice Guy-Blaché remains in New York and continues to make films, however, Solax is struggling. To help pay the bills she begins renting out the studio to other film companies, but in 1919 a fire emerges and a big part of it burns down.

She perseveres and tries to make another film, but during production, there is an influenza outbreak and she almost dies of the disease. Then the business goes bankrupt and anything that remains from the fire is auctioned for pennies on the dollar.

This puts a very sudden and unfortunate end to her career.

After moving back to France with her kids she never makes another film because she is unable to find a job. As she puts it, nobody wants to hire an old, white-haired woman as a director.

It seems like the industry had moved so fast that everybody had just forgotten about her, but worst of all, she was also forgotten by history.

When the Gaumont company publishes a book about the history of their early films, Alice Guy-Blaché's name is nowhere to be found.

When a documentary is made about Fort Lee and the Solax studio is featured, the only person mentioned is her husband.

When an article about the origins of French cinema is published in 1957 her movies are present, but not her name, because the credit is wrongly given to other people. Sometimes her assistants and sometimes even people who had never directed a film.

For decades, as film historians were trying to put the pieces together, she was either getting completely ignored or barely mentioned in passing.

Why? Well, to some people it's because of incompetence, as for others it was the unwillingness to give that much credit to a woman. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle, but the fact that the majority of her films were either destroyed or considered lost at the time certainly didn't help.

In the late 1940s, she began writing her memoirs, sharing her incredibly valuable first-hand experiences from the birth of cinema but not a single publisher was interested in releasing them.

The legacy of Alice Guy-Blaché

After being the only woman filmmaker in the world for almost 20 years, she writes an article in The Moving Picture World journal in which she says that 'There is nothing connected with the staging of a motion picture that a woman cannot do as easily as a man, and there is no reason why she cannot completely master every technicality of the art”.

She discovered and personally trained many great directors and actors, and was a major inspiration for filmmakers such as Eisenstein and Hitchcock.

After she passed away in 1968, it took 8 whole years for her memoirs to get published. Eventually, film historians took notice of her, and slowly but surely she began appearing back in the books, finally allowing for her story to be told.

In an industry that still struggles with diversity even to this day, it is important to remember that once upon a time, at the very beginning of it, there was a woman of crucial importance. And her name was Alice Guy-Blaché.

Learn more: