This is the fifth in a series of guest posts by filmmaker Raafi Rivero.

Several of you have reached out via comments, email, and twitter about continuing the Director's Chair series and I'm glad for all the feedback. One of the most-requested ideas was to do a post on working with non-actors. I'll start with an old saying that comes from our sister profession, photography: The camera looks both ways.

To me, this means that how you approach your subject will do a lot to determine how and whether they open up to your camera. For instance, some street photographers are able to capture the most amazing portraits of regular people just by asking and immediately shooting, whereas other folks either miss the moment or try to sneak shots or "take" pictures from their subjects. People often shy away from these types of approaches. What's the difference? Well, I think a lot of the same principles apply to filming non-actors.

If you are open and giving with how you photograph people, they will open up to you in turn. The same thing applies to film. You must be generous and giving of yourself when working with a non-actor. Explain things to them: you plan to do a take soon, but you'll do a camera rehearsal first so that the team can measure focus. Keep the lines of communication open, be accessible. Non-actors can clam up and become self-conscious or aloof. They don't know what's happening, don't know who to talk to. It is your job, as much as possible, to make sure that your non-actors are engaged in the process and feel comfortable on your set. This will pay huge dividends when the camera is rolling.

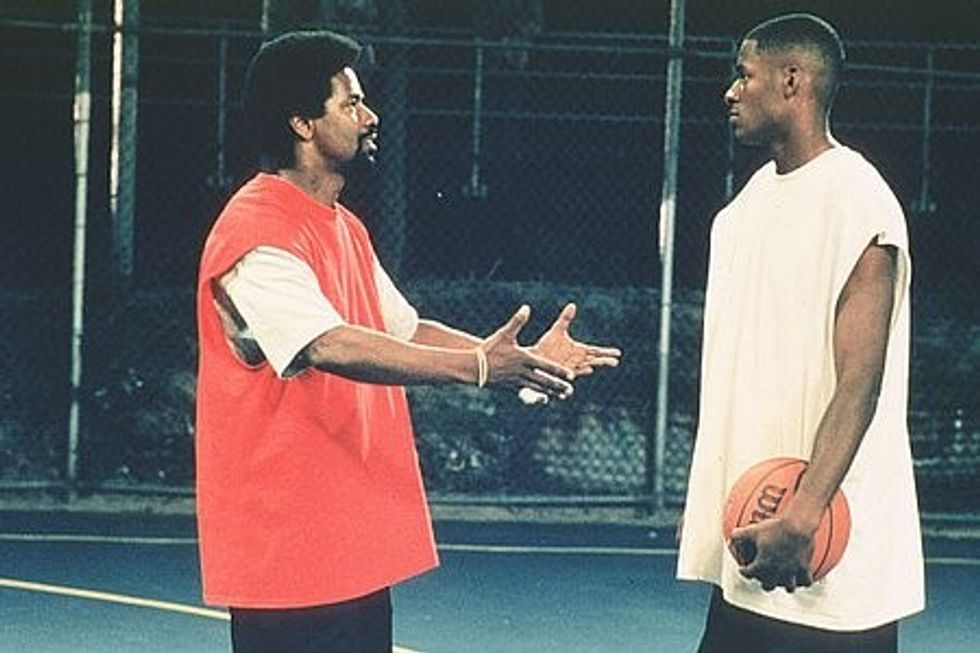

Spike Lee got believable performances from Ray Allen in He Got Game because he let Denzel Washington do much of the heavy lifting. Casting real porn stars in the sex romp scene didn't hurt either.

Non-actors are often intrigued by the process of making films, but this excitement can wear off very quickly once they realize that it's actually hard work. Further, they are not accustomed to being directed or being told that what they are doing is wrong. They get tired earlier, grumpy quicker, and generally don't want to hang out on set all day doing a million retakes. The rule of thumb here is simple and I cannot stress it enough:

With non-actors, prepare to get what you want on the first take.

Because the process of acting is so strange -- saying the same thing over and over, attempting to infuse each performance with something original and closer to the truth -- a non-actor can be excused for not understanding or caring. In their mind it's like, "I did it! Yay! Why do you want me to do it again... is there something wrong?" And from there they begin to become overly self-critical. Trying and often failing to give you that thing you said you liked from four takes ago. Not understanding how to get it back, wanting to go home.

It is very important to be both supportive of them -- first off, they are probably there as a favor to someone, or are highly esteemed in some other profession -- and to make sure that your professional cast, crew and technical people will be able to execute something useable on the first take. Nowhere are rehearsal takes more critical than with non-actors.

“When you cast actors, you try to find the quality you couldn’t beat out of them with a tire iron. That’s where you find the character.”

- David Fincher (source)

Often you cast a friend in a role precisely because of this reason: their natural character or look aligns with something you want to capture on film. The important thing to remember is not to ask them to do more than they’re capable of. I've had it happen more times than I care to count: thinking a friend will be perfect for a dynamic role, getting them on set, and realizing that they look perfect but have the acting chops of an oar. Sometimes if you have a non-actor who’s really wooden, you can direct them down. Have them move and say as little as possible like some sort of psychopath and let the actor you trust do all the heavy lifting in the scene.

Non-actors, in particular, don't look at what you’re doing as a way for them to flex their skills like actors do. If you’re lucky, you find ones who take to the process and develop a natural feel for it. Often, though, they become more and more dependent on what you say as a director. They’re not used to lights and grips and people standing around, so if you tell them say it like THIS, then they do. If you tell them say it like thisssssss, then that’s how they do it. ((Ed. note: whereas many experienced actors hate line readings.)) They rely on you, the director, as being the one regular person in the room who can help them understand what’s going on and how they can do their job better.

Randomly, here's a spot we did at Desedo, working with non actors (obviously):

All of the above said, working with non-actors can be very fun. They’re a lot less diva-ish, and seem to have fun in a lot of parts of the process that us insiders are tired of. And performance-wise, you can get a naturalism that’s irreplaceable.

The key is to make sure you see things a bit less seriously -- like a non-actor would -- and try to relate to them as people as much as possible.

To see all the posts in this series (to date), click here.