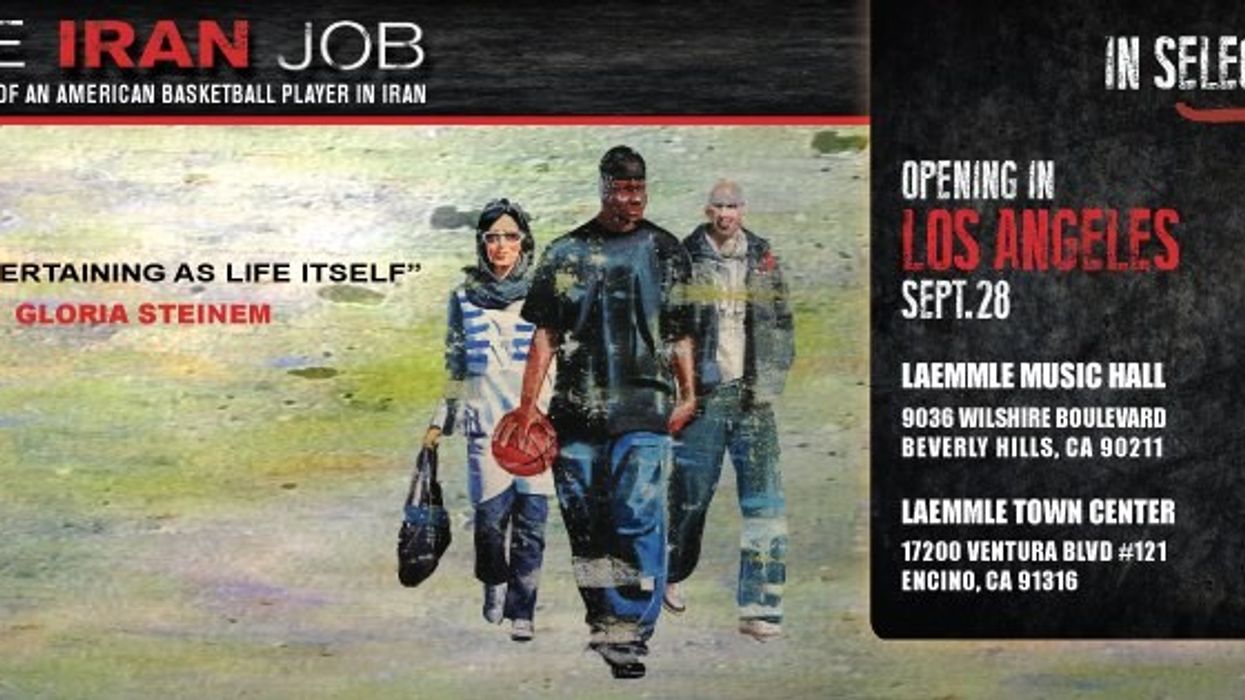

Tapes in Underwear, Documents Down the Toilet: Guerilla Tactics and the Filming of 'The Iran Job'

This is a guest post by Till Schauder (with Sara Nodjoumi).

I’m married to an Iranian woman. She’s smart, beautiful, and tough as nails. (I may be a little biased, though not much…)

In 2007 a friend of ours – actually the fellow who married us – sent me an article about a handful of Americans who play professional basketball in Iran. At that time we were high at war with Iraq and Afghanistan and it looked like Iran – or “I-ran” – would be next on the list, just as it does again now. In the absence of diplomatic relations (we haven’t had an embassy in Tehran since 1979), I was inspired by these athletes, who arguably do more for dialogue between Iranians and Americans than any politician on either side.

I decided to make a film about one such players’ experience in Iran. More importantly, I convinced Sara, my Iranian wife, to help produce it… At that time we were newly-weds living in a studio apartment in Manhattan – obviously with no kids. We thought it’d be fun to take a year off from our lives – that’s how long we thought it would take - and make a movie about something that could be relevant. Five years and two babies later, I can say that it took a little longer than expected. But the film seems as topical as ever.

We thought this would be an easy pitch for networks. Then we learned that most of the players didn’t actually want to talk in front of a camera because some of them had faced severe fines – not from the Iranian side, as one might imagine, but from the U.S. State Department. The State Department argued that the players were breaking the embargo against Iran by making an income in the Islamic Republic. So instead of using these athletes as potential bridge-builders they actually tried to discourage them from playing in Iran. Some players went anyway, and I couldn’t help but be inspired by these guys who took a leap of faith – quite literally in the case of high-jumping basketball players.

Finding the right player - our hero who would take us on the journey - proved more difficult than we thought. My background is in feature films where I’m used to casting the ideal talent – the person that seems best equipped to play the part. So I was picky, and Sara – who’s not at all interested in basketball – even more so. We both wanted someone special – someone so charismatic that we’d want to make a film about him regardless of whether he plays basketball in Iran or not.

After a year of research, several failed attempts with some players, and enough of our own funds poured into the project, we decided we couldn’t force it. We agreed to cancel the project.

Just then, in the fall of 2008 – shortly after Iran’s president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called again for the destruction of Israel – we had a Skype call with Kevin Sheppard, a point-guard from the U.S. Virgin Islands. Kevin was about to start a basketball contract in the Iranian Super League. A minute into the conversation he had us rolling on the floor laughing in spite of the prospect of playing in a country supposedly full of illegal nukes and Islamic terrorists. His easy-going personality convinced us to start filming immediately, even without a budget - which we still didn’t have, because the networks we pitched to were either afraid of Iran, or of us (as first-time-doc-filmmakers), or of both, or they simply couldn’t insure a crew to come to Iran, thanks to the embargo.

But we had found our hero. Kevin had the exact qualities we were looking for – curiosity, a disdain for self-censorship and a disarming sense of humor. He was also very perceptive and an equal opportunity jokester – he made fun of Iranians and Americans alike. These traits created an opportunity to add humor, soul, and positive energy to a film that could otherwise fall into the trap of “another-Middle Eastern-the-world-is-about-to-end” flick.

Originally the plan was to go as a two-person team, Sara and I. But when the journalist visas that we requested were denied it became evident that we’d have to shoot the film under the radar. We decided it was safer if I went on my own, entering as a tourist with my German passport (I’m a dual German-U.S. citizen. The German citizenship made it easier to enter Iran). I packed a small HDV camera, a wireless mic, and one cable – all of it small enough to fit into an unassuming backpack. The (in hindsight very naïve) thought was that if I ever got into trouble I could say I’m just a German tourist filming the sites of Iran.

In this way, I documented Kevin’s season in Iran. But the film quickly became about more than basketball. In my mind basketball was always just a medium – people can easily relate to it. It would allow Western audiences to engage with a country they might otherwise not care about. But through the sport I wanted to delve deeper into the social fabric of Iran, the people and the zeitgeist there. When Kevin befriended the three young women that play such a big part in the film I got a lot more than I ever expected. Thanks to these women his apartment turned into an oasis of free speech, where they talked about everything from religion, to women’s rights and gender roles. And then of course Barack Obama was elected and the Green Movement happened, which provided yet another unexpected story arc.

I’m often asked what it was like shooting in Iran. The fact that I had very limited equipment and no crew definitely created certain technical challenges – mostly for sound actually. But on the other hand it also gave me extraordinary access that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. Since my equipment was so small, and since I was the only member of the crew I literally became a fly on the wall.

The biggest challenge was avoiding the authorities as I was filming. Without a journalist visa I could’ve gotten in uncomfortable situations – as evidenced time and again by filmmakers and journalists who are arrested even with proper documents. Another challenge was getting the footage out of the country. I didn’t want to risk being searched at the airport with the hundreds of hours of tape that I brought home each time. In other countries I would’ve simply shipped the footage back to New York, but in Iran that wasn’t possible. Once again the hurdle was not presented by the Iranian side but by the U.S. side. Thanks to the embargo, U.S. customs doesn’t permit “media shipments” from Iran.

So each time I left the country I hid what I thought were the five best tapes in my underwear hoping I could get these tapes out safely myself. I sent the rest to my mother in Germany, which has much better trade relations with Iran. My mother would then send the footage on to Brooklyn, where Sara and I had moved by that time. Each time I sent a batch of footage to Germany I suddenly became religious, and quite devout, praying to God, or Allah, that the delivery service would not fail me.

I filmed Kevin in Iran over several visits, until on my last trip - in the run-up to Iran’s 2009 election - I was informed that I had finally made it onto a "black list" (for reasons still not clear to us), and was put in detention in a kind of “hotel-prison” inside the glitzy new Tehran airport. Sara was at home – five months pregnant with our second child - while I was in Tehran hand-shredding some not-so-cool-when-you’re-stuck-in-Iran-documents and flushing them down the toilet (e.g. my father-in-law's satirical art, which is banned in Iran).

The detention room in Iran had a television, so I spent the night trying to find something to watch to ease my mind. But the television had only one channel, and it played a loop of the 1982 soccer world cup final between my native Germany and Italy – one of the most painful defeats our team ever suffered. It was like Chinese water torture. However, the following morning I was sent back to New York on the next plane -- a stroke of luck in retrospect given the number of filmmakers and journalists recently arrested in Iran.

Having worked on the film over five years now, Sara and I are surprised – stunned actually – that it seems just as timely now as when we began. Beyond all, we are delighted to finally bring The Iran Job to an audience this fall. We’re financing the release through a Kickstarter campaign, and if anyone is interested in supporting it we appreciate it.

Links:

- The Iran Job -- Kickstarter

- The Iran Job -- Website

- The Iran Job -- Facebook

- Los Angeles Release/Showtimes

- LA Times Review

- The Iran Job -- Huffington Post

- The Iran Job -- The Wrap

Till Schauder, Director/Producer/Cinematographer/Co-Editor: Till got his start in Germany where he wrote and directed the award winning films STRONG SHIT, and CITY BOMBER. After earning a government grant for the arts he made his U.S. debut with the romantic comedy SANTA SMOKES which won several international awards, among them Best Director at the Tokyo International Film Festival and the Studio Hamburg Newcomer Award. DUKE'S HOUSE, about Duke Ellington's Harlem home premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival. For THE IRAN JOB, Till ran one of the most successful Kickstarter crowd funding campaigns of all time together with his producing partner (and wife) Sara Nodjoumi. Through his company Partner Pictures Till writes, directs, shoots and produces for television and film. He has a side career in acting where he occasionally is cast in shows like HBO's Mildred Pierce or a national American Express campaign. Till is a graduate of the University of Television and Film, Munich. He teaches film classes at NYU and has been a guest lecturer at various other campuses. He has also been invited to serve on film festival juries and panels, e.g. at the Munich Intl. Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, Bahamas Intl. Film Festival