Watch: What Abbas Kiarostami Taught Us About Heaven

Kiarostami's celebrated films show the under-appreciated paradise that surrounds us.

[Editor’s Note: We’ve invited one of our favorite video essayists, Scout Tafoya, to premiere some exclusive works on No Film School. Please enjoy the second video in this series, on the legacy of Abbas Kiarostami, who passed away last week at the age of 76.]

Celebrated Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami won more awards than you could fit in a trophy room in his decades-long career, winning special prizes at the film festivals in Cannes, Venice, Chicago and Locarno, and a prize from what feels like every critics group in America. You can find his influence in the films of Naomi Kawase, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Albert Serra, Michelangelo Frammartino and dozens more internationally acclaimed directors. He spoke to people. No less an authority than Jean Luc Godard said once that "Cinema begins with D.W. Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami."

As a cinephile, I looked to him to break my heart and lull me into a dream-like state with his singular rhythms and images.

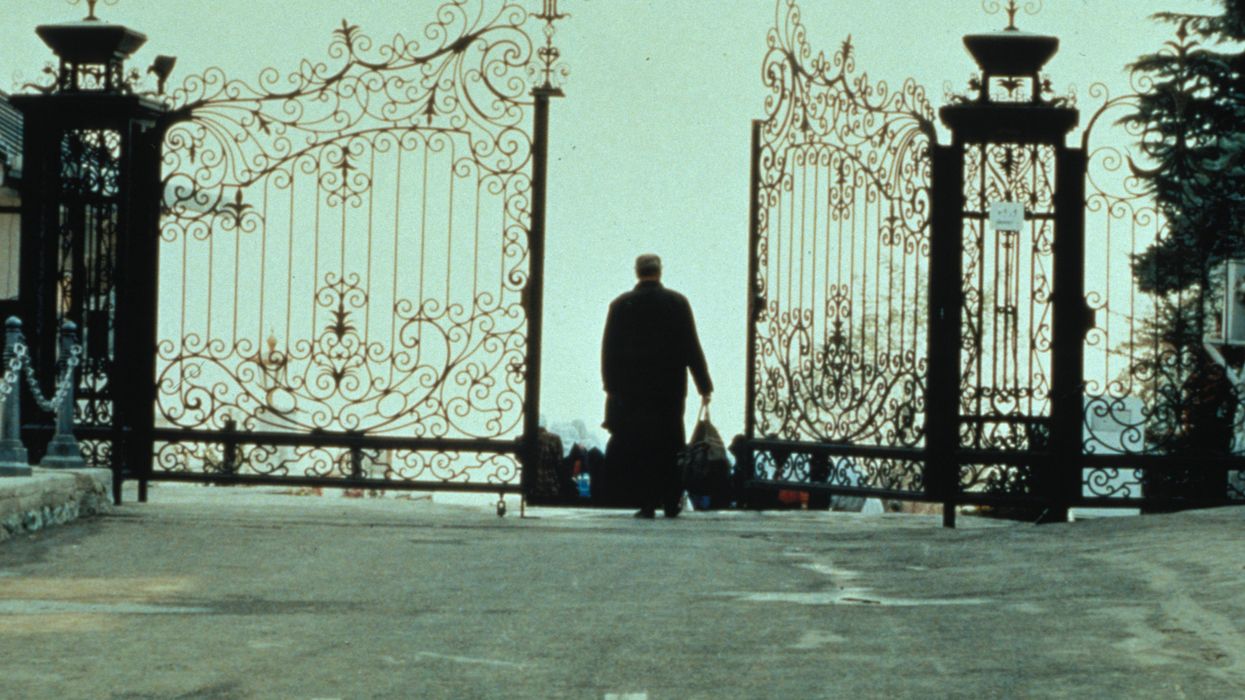

His films seemed more than mere cinematic experiences or objects. They were bigger. More like illusions or dreams. His mix of intense intimacy and awe inspiring landscape photography created a kind of otherworldly space for emotional exploration. He made it seem as though we were watching people dwell in some kind of gorgeous purgatory, unaware of how to handle life's gifts or tragedies, which became its own enthralling narrative, divorced of whatever plot he'd dreamt up. Kiarostami exuded a zenlike comfort with the wretched world, looking at it through his trademark sunglasses, reducing grand existential conflict into something not just comprehensible but hopeful and beautiful.

My video essay below explores Kiarostami's films Close-Up, Shirin, Cannes Palme Do'r Winner Ta'm E Guilass (Taste of Cherry), The Wind Will Carry Us, Certified Copy and Ten.

Kiarostami's beguiling narratives have been a fixture of world cinema since the 1970s and his absence is titanic. He was still inventing new forms, still playing with his own rules, still helping us make peace with our own lives. As a filmmaker, I looked to Kiarostami for guidance and new ways to think about cinema. As a cinephile, I looked to him to break my heart and lull me into a dream-like state with his singular rhythms and images. There will never be another Kiarostami.