Meet the Man Who Created the Director's Cut

Filmmaker's creative rights should never be taken lightly. Elliot Silverstein fought hard to enforce them.

Long before DVDs enlightened audiences to the concept of a "director's cut," creative artists behind the camera fought to bring the director into the editing room, allowing them to have a pass at their footage before studio interference took place. Elliot Silverstein was the man who led that fight.

Best known for his films A Man Called Horse and Cat Ballou, Silverstein was a prolific television director throughout the 1950s and 60s, and it was then that the battle for director's cuts began. After a friendly but earnest conflict took place between him and the producer of a Twilight Zone episode (Silverstein had directed the episode), Silverstein went on to form a committee at the DGA, for years fighting for filmmakers' creative rights.

No Film School sat down with Silverstein to talk about the process of providing filmmakers the right to be involved in post. At 90 years old, he's still working on getting another movie made.

No Film School: When you look back at your career, where do you put the Creator's Bill of Rights now? When you think about it, is in one of the most important things you did?

Eliot Silverstein: I'm very proud of the legacy. I think it really defined, to a very large extent, what the Director's Guild of America is, apart from its role as a trade union. I am proud of having left the creative rights concept and the specifics associated with it. I'm very proud of that.

I don't know how to describe it, but early on, the corporate influence on a given piece of work was much stronger than it is now. Directors had very few defined rights to protect the work. For instance, the initial version of the contract between directors and producers read something like this, "The director shall have the right to view," the word "view" was important, "the first rough cut," whatever that was, "and to make any suggestions he had to the associate producer," whoever that was. The roles have changed since those days. That tells you that it was further down the line. He didn't have firsthand control.

My first task was to establish what suggestions meant and who the associate producer was and why it'd have to be the associate producer instead of the producer and why the director didn't have primary influence over the material that they directed, subject only to the labor laws, which gave the corporation ultimate control.

"Short of substituting a director for the corporation, it defined what rights a director had as an artist."

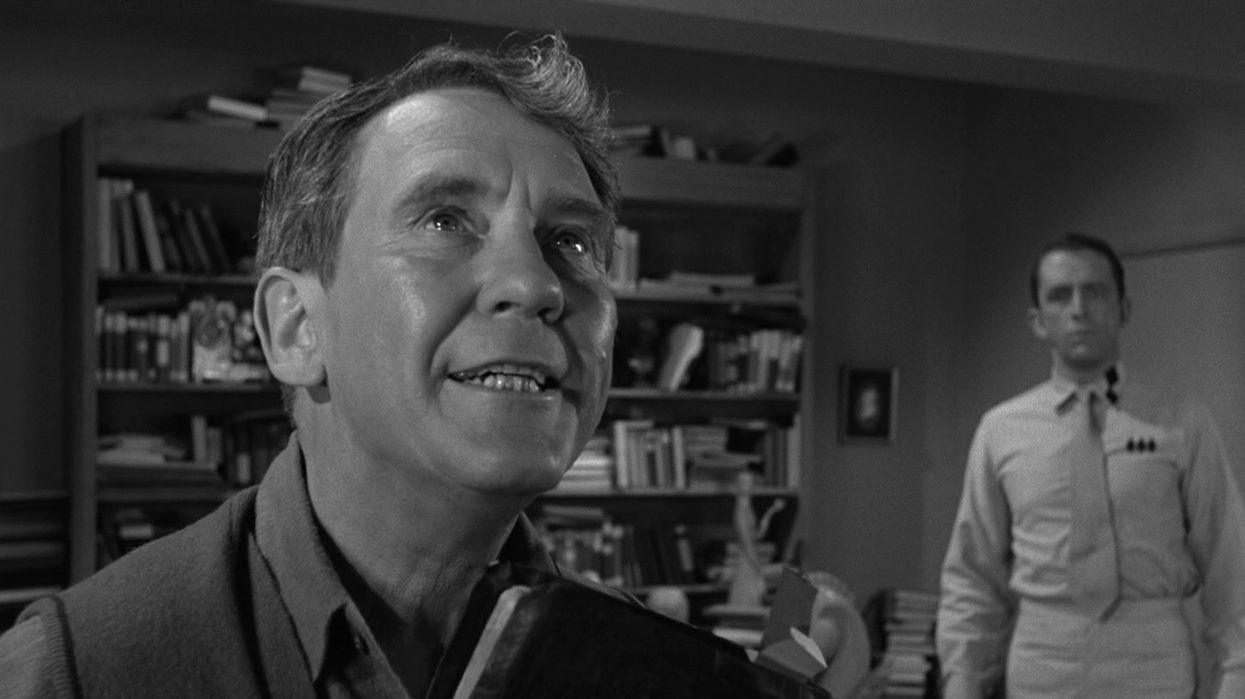

NFS: The whole movement grew out of your time on "The Obsolete Man" episode of The Twilight Zone.

Silverstein: There was one sequence where there was some dispute between me and the editor. I had an expressionistic view of that piece, and he had a more literal view. There was a sequence in which a chorus of SS-type people were advancing on one of the other characters, a whole chorus, and they were just going, "Grr," getting louder and louder and louder as they advanced, and eventually converged on him and attacked in an unseen way because they were in a football huddle.

He cut that rather literally. I wanted to delay the advance to create a greater tension as the growl they had on chorus increased in volume and they advanced slowly to it. He wanted to get the advance over with it. There was a big to-do about it.

NFS: You had this conflict, but it didn't transcend into the personal?

Silverstein: No no, it was just simply with the editor. By the time we resolved it, the cut had been made and they were ready to go on the air, and I couldn't really do what I wanted to do. At that point, I consulted Joe Youngerman, who was the secretary in charge of the Director's Guild, and found out what rights a director had. He pointed out to me the quote that I made to you a few minutes ago, and I said, "What do we do about that?" Joey said, "What do you want to do?" I said, "I want to change it." He said, "You have to negotiate with the company. Let's do it." We did it under the initial leadership of Frank Capra. After that, he moved on and I took over and led the so-called creative rights movement for about 27 years.

NFS: That's a long run.

"The corporation was not happy with what the individual was doing, so they had to find an individual that they approved of."

Silverstein: It is. A lot was established because it was influential all over the world. Short of substituting a director for the corporation, it defined what rights a director had as an artist.

NFS: With things like Marvel Studios taking off, do you feel like the director is losing some of that ground as an individual creative force? For instance, Star Wars fired Colin Trevorrow, and then they fired Chris Lord and Phil Miller and Marvel fired the great English director Edgar Wright from Ant-Man.

Silverstein: You say "they." You see, the minute "they" or "we" comes up, it's inevitably a corporation. I'm more interested in the individual fortunes, the individual visions. I'm aware of what you're talking about. The corporation was not happy with what the individual was doing, so they had to find an individual that they approved of.

"They were afraid the directors would push for more power, and eventually, that, of course, translates into money."

Silverstein: When I first came aboard the Director's Guild train, the influence the directors had was based on the power of those that had preceded us, the really great motion picture directors, because film for television was relatively new. One had to substitute rights for power. That's really what it was all about.

I'll give you an example going from the sublime to the ridiculous. When Frank Capra headed the Creative Rights Committee, which came about because of my interest and insistence that there had to be some rights for directors, we met with labor relations people who didn't understand the first thing about moviemaking. They were labor union people. Their job was to hold the line on costs. They would not budge.

The issue at that time was to make a director's cut. That is, to give the rights to a director to cut the film or to instruct the editor to cut the film the way they saw it, the way the director saw it, not the way anybody else saw it, and a limited amount of time in which to do that. Now these people said, "No. That's holding up production, or the director will use that right to blackmail us, to delay the orderly production of a television show."

"'We see how much you care, and so we will grant your request for a director's cut.' That's where the director's cut came from."

They were afraid the directors would push for more power, and eventually, that, of course, translates into money. They refused. I remember the conference that the directors on that committee had with Capra. He made the following proposal: "The Director's Guild will agree to a list of 12 names of any directors we mutually agree on, beginning with David Lean and going anywhere, again, any directors that we can mutually agree on, and we will transport them from wherever they are, at no expense to the companies, to complete the work of a director in post-production, if the companies in their unilateral view feel that that director is malingering."

Now that's pretty broad. It embarrassed the labor relations people, because they were not used to a union saying, "We want you to believe that we're really interested in the quality of the result, the individual vision of the result. We're not looking to do anything. We're gonna give you everything. Just give us a break."

They asked us for 15 minutes, and when we came back they said, actually the quote was, "We see how much you care, and so we will grant your request for a director's cut." That's where the director's cut came from.

NFS: Now is that list still in effect at the DGA?

Silverstein: Never been used. It was a tactic, but if we had been called on it, we would have followed through. Now that's the sublime.

I was scheduled to do a television show at a major company, and I showed up with my script to the little dormitories where the producers lived and worked. In the corridor outside a number of offices, there were a number of other directors walking around the corridor with scripts in their hands. I couldn't really figure what that was.

I went in and spoke to one of the producers and I said, "Where do I go to work? I don't have an office." He said, "Out there with them." I realized that's what they thought of directors. They had no office, no place to sit down, no desk. They were to wander the corridors or sit on the stairways and do their work.

I said, "All right, I know how to handle this." I went outside. I asked the assistant director aside and the production manager aside, to meet me on the street. I sat down on the street and we had a conference, with everybody laughing, of course, secretaries putting their heads out the window and laughing at what we were doing. I had a production conference right there on the street, holding up traffic.

"You would think that somebody who's responsible for the expenditure of all of the money that it takes to produce a show would be treated with more courtesy than they treated us at the time."

Eventually one of the executives came along in a big black limousine, "What's going on?" I said, "Nothing, sir. We're preparing a television show." "Why are you out here?" "This is clearly where the company wants us to be, because they won't allow us anyplace to sit down or to work inside, so the natural conclusion is they want us to work in the street, which is what we're doing." He said, "Just a minute," and he went inside.

Five minutes later we had a desk. I had a desk and a place to sit down.

That extended the clause that says we have to have a desk with a door that can be closed and a telephone, near facilities, and a parking space. That's the ridiculous part. You would think that somebody who's responsible for the expenditure of all of the money that it takes to produce a show would be treated with more courtesy than they treated us at the time. I had to pull some kind of a stunt like this in order to call their attention to the absurdity of their practice.

Everything between those two points, consultation, and the things that flow from consultation with the producer are part of what filled in the blank between those two poles.

NFS: One thing I wanted to ask about was, in some of your interviews over the years, it's clear you've paid a lot of attention to the way technology impacts director's rights, colorization in the '80s, director's cuts on DVD in the '90s.

Silverstein: Yes, but all of those are subsequent. The main thrust does not change, the director's right, the director as an artist. Everything else changes and technology just follows. There will always be changes in technology. There will always be changes in practice. There'll always be changes in financing. The core is the right of an individual human being who is assigned the job of translating this material into a movie has not changed.

I think most directors have a vision and want to see it executed. That's where the problem arises, because very often, producers, whether or not they have artistic instincts, also have visions, and those sometimes collide.

NFS: You once said you used to hold up a piece of paper over the lens for parts of the shots you didn't want them to use.

Silverstein: Yes, and this has to do with editing rights. What would happen was the cameras would roll, and before you'd call "action," the actors might be unprepared. They would just be ready and the cameras would roll and there would be a period perhaps of five or 10 seconds, which would provide mischievous producers with pieces of film that I didn't want used. I realized the only way to do this was to block the lens until I said, "Action," and then take the paper away from the lens, so that "Action really meant Action" and not a delayed cue to begin. I wrote something on the paper, I think which was, "Actors not up to speed." When they were up to speed, I'd take it away.

NFS: When people talk about the history of directors taking that kind of power, for you it was a practical battle, and theory didn't seem to be a big influence.

Silverstein: If you hire somebody to create something, you let that individual create it, and that creation is part of an imagination, an imaginative process. The development of corporate influence over this interrupts that process very often and substitutes corporate views for individual views, which that may be a larger comment on American life, including political life, though that's too big to go into at this point.

NFS: Do you feel like it hurt your career to fight as hard as you did for creator's rights?

Silverstein: Yes.

NFS: Do you regret it?

Silverstein: No.

NFS: Were there moments where you felt like your powerful advocacy for director's rights hurt you getting later projects off the ground?

NFS: No question about it. No question. I was thought of as the villain by some of the corporations because what I was doing was decreasing their power. If there's anything that they resent more than anything else, it's reduction in power. I was saying the directors had the rights—not the privilege, but the rights—to do this or that or something else, whatever the specific happened to be.

It was difficult to them, although I must say when we started to negotiate with the executives, which was the second meeting we had, I found that the top executives really were quite reasonable and understood what we wanted and why. They felt that we eliminated some of the difficulties further down the corporate line, as to why things were delayed and why they weren't delivered on time, etc etc. Our efforts did in some respect help them streamline their own process.

To learn more about the DGA and Creative rights you can go here. In addition to a Man Called Horse and Cat Ballou, available on many streaming services, several episodes directed by Silverstein of the show Route 66 are available on Hulu. You can read further about the battle against colorization in this 1987 New York Times article.