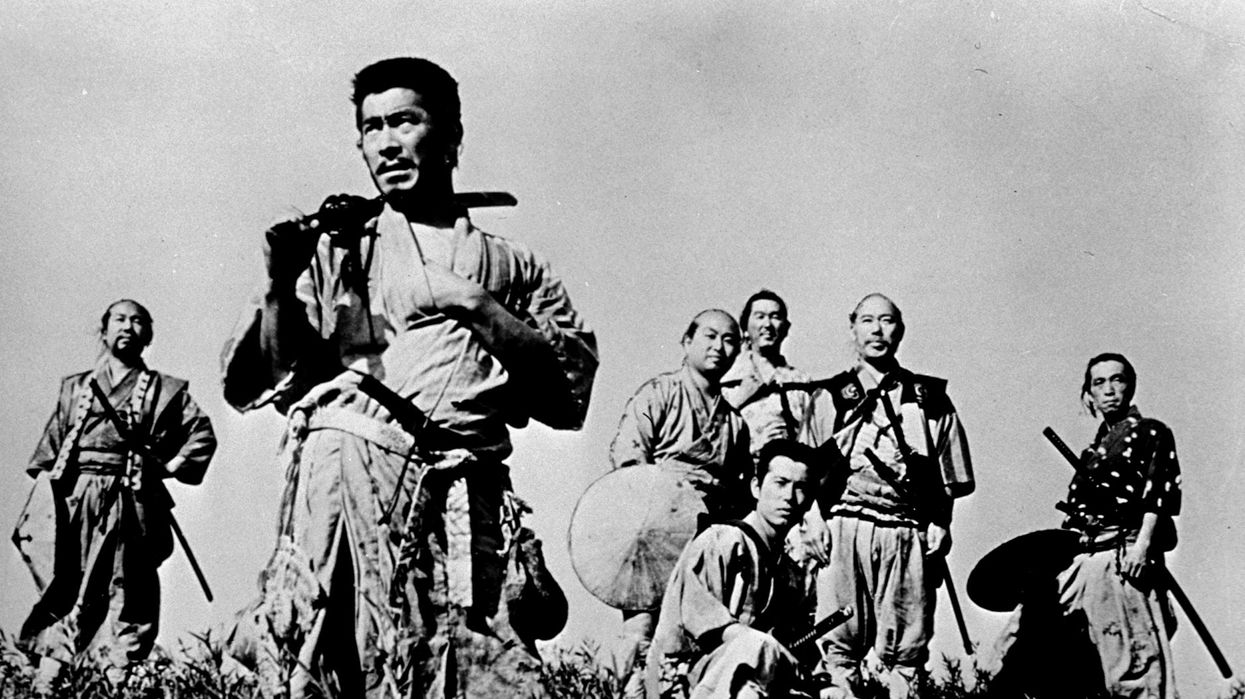

Watch: What 'Seven Samurai' Teaches Screenwriters About Story and Structure

Akira Kurosawa's 'Seven Samurai' is one of the most influential films in cinema history. Here's what the 1954 classic teaches us about screenwriting and structure.

As Jack from (Jack's Movie Reviews) remarks at the beginning of his video, Seven Samurai's influence on popular film (and particularly, American film) is vast. Countless filmmakers, including George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, have drawn inspiration from Akira Kurosawa's 1954 masterpiece, and its characters, shots, scenes and even "narrative beats" have been quoted time and again.

Jack's video focuses on the film's script and story, written by Kurosawa along with longtime-collaborators Hideo Oguni and Shinobu Hashimoto, the latter of whom passed away last month at the age of 100. Specifically, he looks at how the film's structure plays a large part in taking what could be two potential problems—its huge number of characters and epic length—and "not only mitigate...but turn them into assets."

The Seven Samurai and Structure

Seven Samurai is a very long movie, clocking in at "just three minutes shy of three and a half hours," but although it has a lot to say, "it still manages to say it efficiently." Just a few minutes into the film, the story has already set up its central conflict: bandits have attacked a village, making it impossible for the villagers to live in peace, and necessitating the recruitment of the various Samurai.

The introduction of each of the characters is handled in a unique and novel way: when Kambei, the leader, is introduced, he is shown shaving his head to disguise himself as a priest in order to enter a house and rescue a hostage. In his review of the film, Roger Ebert wondered whether or not this scene "create[d] the long action-movie tradition of opening sequences in which the hero wades into a dangerous situation unrelated to the later plot."

The film's first hour is devoted to the gathering of the Samurai and developing their characters, and even after that, the film still "takes its time to ensure that the audience knows what's at stake."

"It's only through writing scripts that you learn the specifics about the structure of film and what cinema is"-Akira Kurosawa

The story takes place over the course of a year, and this passage of time is reflected in various ways: the changing of seasons, the regrowth of Kambei's hair, the arcs and resolutions of various side plots. Each of these contributes to a sense that this is "one story that is the result of many."

The film's final battle is not only significant because it is its own story—complete with a beginning, middle, and end—but also because it is inextricably connected to what has come before; each of the film's preceding incidents and threads have woven together to make the epic climax that much more impactful. Not only is the sequence visually stunning, but it also obtains further weight from its narrative.

Comparing the film to its American counterpart, The Magnificent Seven (1960), Jack finds a key difference in that Kurosawa's film features "no throwaway characters. They each have their own reason for wanting to help the villagers."

The critic Michael Jeck is cited by Roger Ebert for his view that Seven Samurai is "the first film in which a team is assembled to carry out a mission--an idea which gave birth to its direct Hollywood remake...as well as The Guns of Navarone, The Dirty Dozen...and countless later war, heist and caper movies." Even Stanley Kubrick's The Killing, one of the first modern heist movies, has birthed countless tropes (such as bandits in fright mask disguises) and that film was released two years later.

If it's true that Kurosawa's 1960 film, Yojimbo, remade as A Fistful of Dollars, gave birth to the Spaghetti Western, and that 1958's The Hidden Fortress is an acknowledged and heavy influence on George Lucas and Star Wars, perhaps Ebert is right in saying that this "greatest of filmmakers gave employment to action heroes for the next 50 years, just as a fallout from his primary purpose." His primary purpose, in Ebert's view, was to make a Samurai movie that was both rooted in Japanese culture while "arguing for a flexible humanism."

The essential fact of the culture clash between the peasants and Samurai—that they must never mix and that they are both resented and needed—is part of what gives the story such heft, and yet, ironically, is part of the film that often gets lost in translation.

Kurosawa was a monumentally important filmmaker, both as a Japanese director and as an influence on world cinema. Considered to be the most Western of the great Japanese directors, his films reveal a cultural synthesis, a visual and narrative give-and-take that resulted in films like Ran and Throne of Blood, two later classics based on Shakespeare's King Lear and Macbeth, respectively.

While celebrated as a visual stylist, Kurosawa himself remarked that "It's only through writing scripts that you learn the specifics about the structure of film and what cinema is" and this is very evident in Seven Samurai.

As Jack shows, the film manages to juggle a huge cast, epic length, and massively complicated sequences with ease due to a humorous, dynamic, and dramatic way of storytelling.

Source: Jack's Movie Reviews