65 Super Bowl Commercials, 2 Oscar-Nominated Shorts, and Some Tough-Love Filmmaking Advice

Bryan Buckley, who's called 'the King of the Super Bowl,' gives some real-world advice about breaking into commercial directing.

Bryan Buckley is the King of the Super Bowl. At least, that's what the New York Timesdubbed him, along with "the 30-second auteur." They're fitting monikers—Buckley has helmed more than 65 Super Bowl commercials. His spot this year, starring John Krasinski and Chris Evans, was for Hyundai. Buckley is highly regarded across the industry for his gift for casting first-time actors, his eye for detail, and his intrepid spirit.

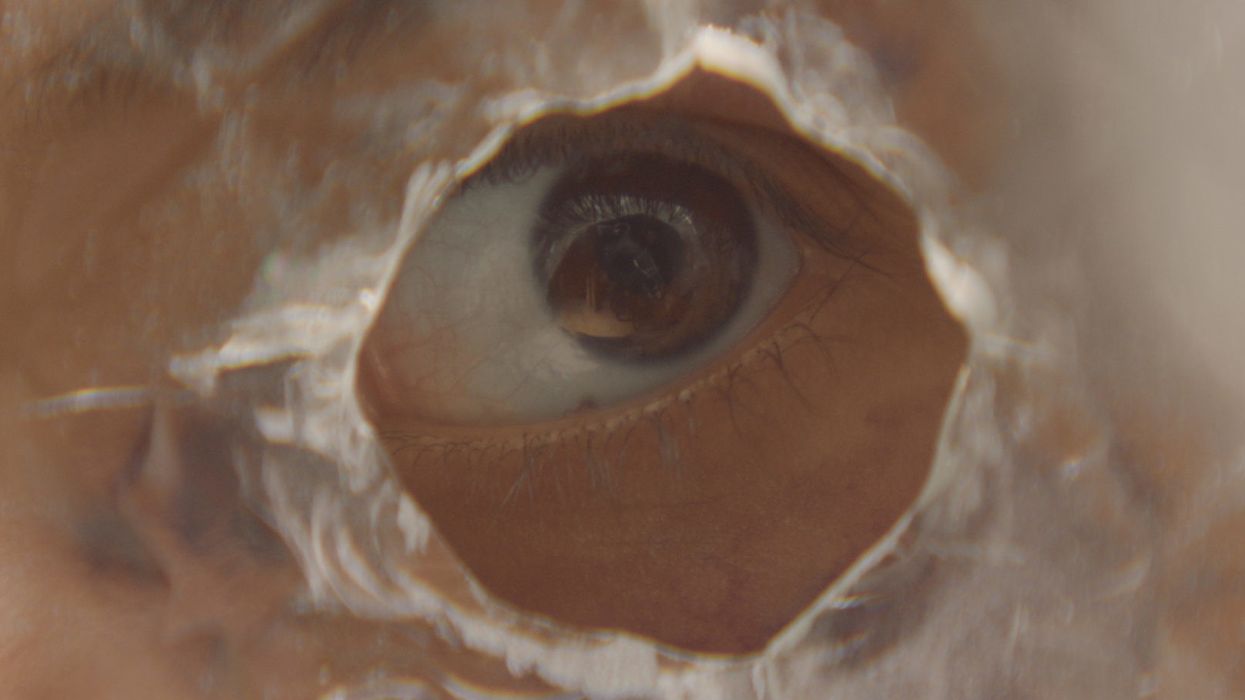

Buckley has parlayed his commercial success into multiple features and two Oscar-nominated shorts. One of them, the devastating Saria, is nominated this year. (We interviewed Buckley separately about the film, along with other directors of this year's Oscar-nominated shorts.)

No Film School sat down with Buckley to discuss why he thinks first-time filmmakers shouldn't jump at the first opportunity to make a feature, why shorts are better calling cards than commercial spots, and how he maintains his vision while working with clients.

"If I said, 'Super Bowl commercial vs. short—what's going to have more impact?' The answer is, believe it or not, the short films had more impact. Crazy!"

No Film School: You now have two Oscar-nominated shorts. What did these two opportunities do for your career?

Bryan Buckley: Honestly, up until my first Oscar-nominated short, I didn't really think a short could have a major impact. If I said, "Okay, Super Bowl commercial vs. short, what's going to have more impact?" The answer is, believe it or not, the short films had more impact. Crazy!

I used to be so against shorts. Like, "Why wouldn't you just shoot a commercial and get paid for it, versus shoot a short, not get paid, and then what?" But there's a whole world of shorts out there. The exposure can outweigh having a Super Bowl spot if you get in the festival circuit, get an Oscar nomination, or do well with it online.

Asad [Buckley's first Oscar-nominated short] had a huge festival life and then it had an Academy life. We entered it into every festival. We traveled with it. I ended up buying the rights to the book that my short was based on, and I did a feature called Pirates of Somalia.

NFS: What have you taken from your prolific experience in commercial work to your narrative filmmaking?

Buckley: Efficiency. In shorts, specifically, it's about what's in the frame. What is the information? The brain is taking in a lot more than you think. If there's a book on the bookshelf in a shot, even though it doesn't matter for the scene, you're going to read it. Are those words helping establish character?

This also applies to commercials. Everything is a part of the story. This is true even for a silly comedic piece. I did a spot with John Krasinski and Chris Evans for the Super Bowl [below]. The detail in that spot is all about character. When you shoot commercials, you have to make a lot of hard choices, and layering easter eggs makes the spot "sticky."

NFS: You have a great command of the economy and storytelling. It's a rare commodity these days.

Buckley: I've watched lots and lots and lots of shorts. I always appreciate filmmakers that are efficient, who are making decisions that aren't extraneous. The whole idea with a short is that you have to tell a story in a short period of time. You can have a long shot—we had long shots in Saria. But they're there for a purpose, not just because I want to let the camera run for three minutes.

NFS: Do you have any advice for up-and-coming filmmakers who are trying to land commercials?

Buckley: Go shoot shorts. Do an unbelievable one and that will open things up. Don't do spec commercials. It's a big waste of money and time.

The great thing about shorts is no one's looking over your shoulder. It's completely different when you start introducing the agency and client. And so, the balance of a commercial director is: how do they manage to sort of move their vision without pissing everybody off? That's really the gift. Because if you piss an agency off, or you piss a client off, they never will hire you again, period. There are 1,000 directors out there. They'll just use somebody else. It doesn't matter who you are.

"If distribution on your first feature fails, you're marked a failure. That's the business side of Hollywood."

So you have to figure out how to [balance your own vision with the client's], especially when you're young and coming out of school. No one believes in you. No one thinks you know what you're talking about. So, you go into a meeting, and everybody's like, "Do it this way." You have to prove them otherwise. I think a short can do that, if it gets some accolades.

Someone was asking me the other day, "If you're going to spend a lot of money on a short, why not just shoot a low-budget feature?" The answer is you shouldn't because ultimately you have to deal with distribution, and that's a whole other business. If distribution fails, you're marked a failure. People will actually look at you and say, "I don't want to do business with you because you failed at distribution." That's the business side of Hollywood.

If you make a first feature that fails, you're running a tremendous risk. You could really screw up your career very early. I think you're better off sort of doing your shorts, honing your skills, picking up commercials, maybe a music video. You have to get your skill level to the point where you're feeling good, and then go make that first feature. You learn every time you shoot. I'm still learning all the time.

NFS: I think that's really good advice. These days, so many people say things like, "Just go out and shoot your first feature, and you'll learn, even if it's a failure." But I think it's really pertinent to think about director jail. It's real. It happens.

Buckley: Oh, trust me. It's very real. I've been there. In 1999, I went off and did a feature that never saw the light of day. It was a shit show. It had nothing to do with me. Everything in the shoot went great. It was all the business shit after that, which was completely out of my control. Decisions were made without me. But you, as a director, are on the hook for everything, 100%. I've been kicked in the face enough to know.

Let's just say you make a feature and it doesn't get into Sundance. Maybe that's because this year's Sundance isn't doing that kind of movie. They did it last year. That's not the type of film that they're really interested in right now. Now, you've lost one of your biggest marketplaces. You're in a free-fall in the U.S. You've just spent your parent's money and money that your grandmother gave you, her trust fund, you're out a million dollars and you're just spiraling with this thing. No distributor is going to touch it at this point. You're not going to have a good sales price if you sell at all. It's really difficult. Netflix isn't going to come to save you. And now, you're stuck with this thing. Maybe if you walked before you ran, you could have done a little short as a test concept and gotten it right.

"You're running a tremendous risk and you could really screw up your career very early if you fail at a feature. You're better off doing your shorts, honing your skills, and picking up commercials, maybe a music video."

When we did Asad I never worked with refugees before. I'd never been to Somalia before. We learned so much. Especially if you're going to do risky sort of filmmaking, then maybe you should at least test it out first if it's going to work.

Let's say you are trying to break into commercial directing. If you have a good short, an agency person or a producer who's going to pick you will see it and say, "I'm going to believe in this person and take a risk on this person. I can see he's got something, and I'm going to discover him." That discovery factor is huge. But when you do some bad commercial or a spec spot or whatever, you're not going to have that discovery opportunity. That good person is probably not going to see your talents. That's why I'm very pro-short.

NFS: You mentioned bringing your own vision into commercials. I imagine that's hard, given the fact that you've got a predetermined story with a lot of stakeholders. How do you manage it?

Buckley: Well, you always bring your own vision. Taika Waititi, for example, is a part of my [commercial production] company. I had this exact conversation with him about Thor the other day. When he went off to make Thor, I was like, "Dude, I don't know how you're ever going to get your voice into Thor." But he did. In fact, as much as I like Jojo Rabbit and I think it's an amazing film, I was actually more impressed that he somehow was able to get his voice into Thor. Like, how do you win all those battles with the studio? But in the end, I really wasn't that surprised because no matter what he does he brings his voice to it. You have to stay consistent.

For me, on commercials, I would say the casting is everything when it comes to my voice. I look at thousands of hours of casting. I usually can see something in people that people don't see. It's just what I do. It's a gift. Casting is, in the end, the cornerstone of everything. You can see if a person is going to be interesting and textured and layered—all the things you need them to be. And then you have to sell that casting to the client.

"If you try to emulate somebody else, you're like a bad Prada knockoff."

I get mad at myself when I have to use the same person twice in a commercial. Sometimes I do because they're that good. But generally speaking, I'm always looking to try to find someone new. Last year, for the Super Bowl, I did an Xbox spot with this little boy, Owen. The casting spec was for kids who were physically challenged. I did casting calls for kids all over the country with different disabilities. We had to find a real kid who could act. The client was trying to originally do it for Fortnite, so I was supposed to cast a kid who was 15. And this kid came in who was nine. You'd think that Xbox was going to be like, "Let's get a new kid because we need to tie into Fortnite." But Xbox looked at the kid and they go, "No, we need the kid, forget Fortnite." That was really about casting. The agencies respect my choices at this point.

But still, you still have to sometimes sit there and get into arguments about talent. Because if not, people have a preconceived notion of what that person is going to look like or how they're going to make them laugh or what they're going to say. I always go into stuff remaining open. "Let's see what happens. Let's get the callbacks and figure it out."

The other thing is, you have to shape your voice. If you start trying to be like, "Oh, I want to shoot like so and so," in you're in a huge amount of trouble. It's got to be your movie. Your vision. You can use references, but use them with your own voice. If you try to emulate somebody else, you're like a bad Prada knockoff.

NFS: No one wants to be that filmmaker.

Buckley: I wouldn't even want to want to be a Prada filmmaker, to be honest with you. Neither the knockoff nor the Prada!