The Hollywood Director Who Doesn't Actually Exist

Alan Smithee is one of the most legendary Hollywood directors of all time. (Not too bad for someone who doesn’t actually exist.)

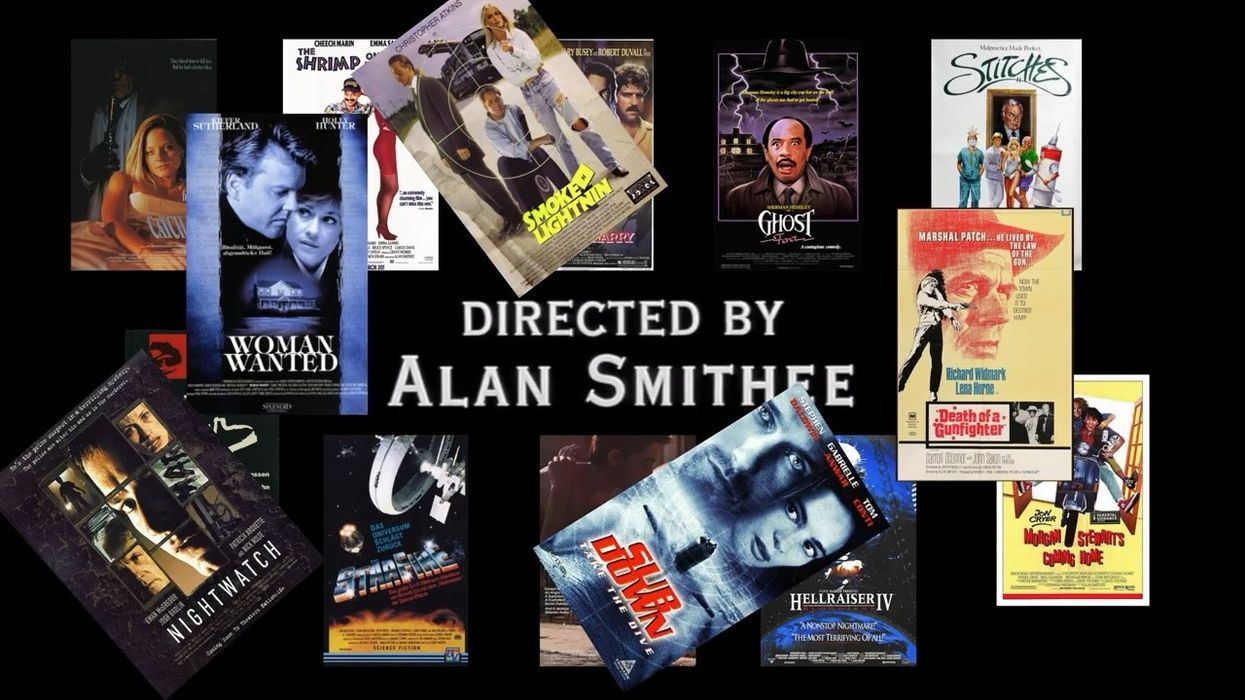

That’s right—Alan Smithee is not a real person. But despite that little technicality, over the course of his nearly 30-year career, he managed to direct dozens of movies, plenty of TV show episodes, and even some music videos for A-list artists.

So how is that possible? Check out my video for some answers and let’s dive deeper into it.

A quick history lesson

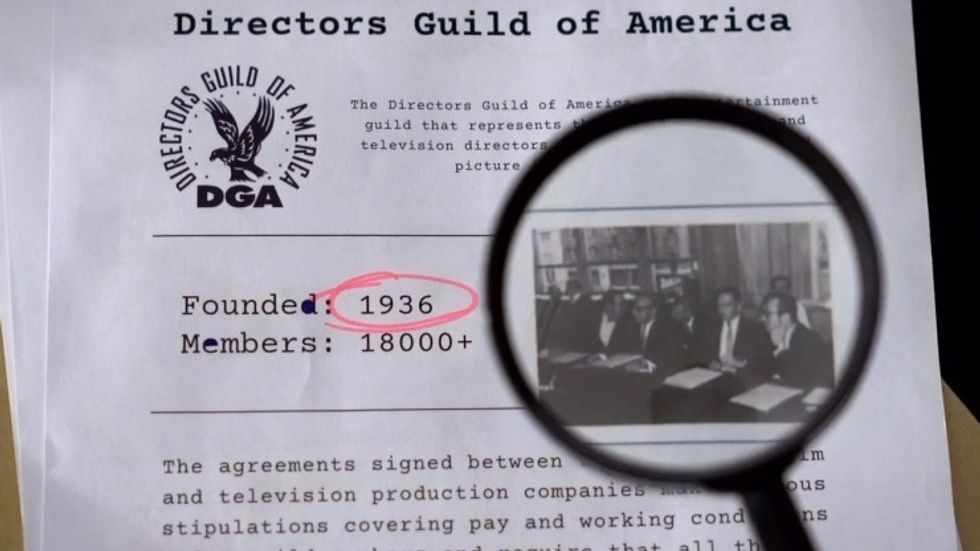

To understand who Alan Smithee is, we need to first talk about the Directors Guild of America.

Founded in 1936, its main goal has always been to protect not only the legal rights but the creative freedom of its members.

Back then, most directors did not have a lot of authority. Instead, they were just regular employees for the studios who got hired on multi-year contracts and worked on whatever projects they were assigned to.

For the most part, the general public didn’t even know who directed a movie, just which studio it was coming from.

This was of course, on purpose.

This was to prevent them from building their own reputation and potentially gaining too much negotiation power, but also to make sure studios controlled every aspect of the movie.

In an effort to change that, King Vidor and a few of the leading directors at the time formed a union to collectively negotiate with the studios and guarantee the right to be actively involved in all aspects of the filmmaking process.

They wanted to establish the director as the most important person behind a film. To further help build their image they required proper credit from the studios and did not allow the use of pseudonyms.

Regardless if a movie turned out good or not, each director had to take all the praise or criticism that comes with it.

When things go wrong

During the 1960s, creative control was getting more and more important for directors.

It was a movement known as auteur theory, or the idea that while filmmaking is a collaborative art form involving hundreds of people, ultimately, the vision reflected on screen is that of the director. And they are the person who can make all of the decisions from the very beginning to the very end.

For the 1969 movie Death of a Gunfighter, however, that was not the case.

During production, director Robert Totten had a lot of creative differences with the lead actor Richard Widmark, and since the latter was a fairly big star at the time, he managed to convince the studio to replace him.

Eventually, Don Siegel was brought in to complete the movie, but prior to its release, both directors refused to take the credit as it did not represent their own creative vision.

One had only filmed about a third, the other was never really in charge anyway, and the final edit of the movie had about an equal amount of footage between the two.

It was a messy situation. And since it wasn’t fair to either of them, the Directors Guild of America had to get involved. The only way to solve the situation was to invent Alan Smithee—a completely fake director with the sole purpose of essentially taking the blame.

And that’s how the movie got released.

Ironically the critics ended up praising the direction of this unknown director and it was received rather well, but it wouldn’t be long until the quality of his movies began to decline.

How it worked

Over the years the union would allow more filmmakers to detach themselves from their movies, but for that to happen, there was a specific set of rules.

First, you would have to appear in front of a panel of the guild, almost like at a court hearing, and prove to them that you had lost creative control.

That could be because of the studio interfering or a budget cut. Simply disliking the end result was never considered enough.

If approved, they would remove you from the movie and credit it to Alan Smithee, but going forward you were required to never acknowledge any involvement in the making of it or discuss the reason why you chose to disown it.

The only way this could work was if it remained a secret.

Since the only movies he could make were the ones that nobody wanted to be associated with, for almost 30 years Alan Smithee was quietly building his reputation as one of the worst directors in Hollywood.

But despite that, he managed to not only get consistent work, but even land some pretty interesting projects. The TV version of Dune for example, which was re-edited by the studio in such a way that David Lynch wanted nothing to do with it, or the sequel to Alfred Hitchock’s The Birds, which was apparently so bad that Tippi Hedren who started in both was said she hates to think what Hitchcock would say about it.

In the public eye

For the most part, people outside of the industry weren’t really aware that this was happening, or at least not until 1997, with the release of An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn.

The movie is a meta-comedy about this whole situation and follows the story of a director who wants to use the Alan Smithee pseudonym but cannot, because... it is also his actual name.

During the editing stage, however, the real-life director was so dissatisfied with the result that he had to resort to using the pseudonym. So the Alan Smithee movie about Alan Smithee was directed by Alan Smithee.

At this point, the secret was out, and it was pretty much the end of his fictional career. Basically, nobody would want to see a movie directed by him because it was a clear indication that something had gone wrong during production and it was probably going to be bad.

Since then the Directors Guild of America has allowed a few rare uses of a pseudonym, but all of them have been publicly known.

Unless… the next Alan Smithee is already among us... and we just don’t know about it?

We shall see.

Follow Toni on Twitter.

Source: Toni's Film Club