Scorsese and Tarantino's Chat Is the Best Thing You'll See Today

It's not often that two of our greatest filmmakers sit and chat. And even less often they let us listen. Check out this interesting conversation between Scorsese and Tarantino from their meeting at the DGA.

We're in a fantastic era for filmmakers. There has never been more outlets or cheaper ways to get your stories told. But two guys are still doing it the old Hollywood way. But one of them is harnessing the power of the new as well. Martin Scorsese used 2019 to make a Netflix movie and Tarantino used it to make a movie about a TV star he wished became famous, and an actress he wished wasn't murdered.

Both of these ideas feel like they came from an alternate reality. But they exist in ours. Now, the DGA, or Director's Guild of America, recorded these two talking about their years, filmmaking, and what's to come. You can read the whole interview here, but we're going to take a look at a few great quotes from the article and analyze them.

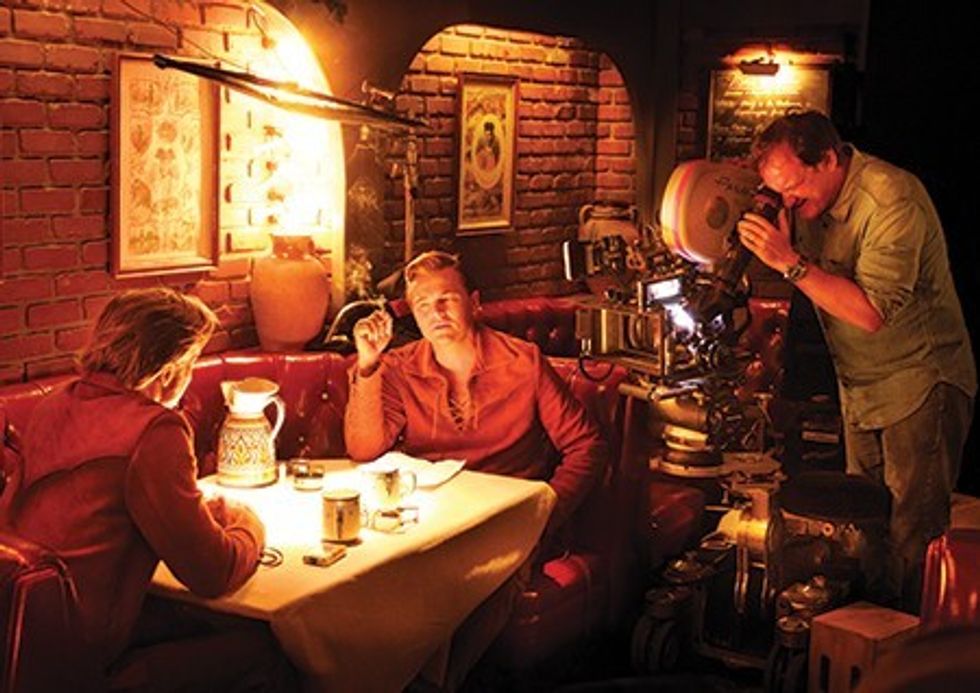

Wise Guys: A Conversation Between Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino

On the pacing of The Irishman:

QT: Well, let me ask you a question about the movie you're doing now because you're dealing with, I think, the longest canvas you've dealt with. It's quite a few hours, right?

MS: Yeah.

QT: So how has that affected you as far as pacing is concerned?

MS: Interestingly enough, I figured out the pacing on the page this time with the script that [Steven] Zaillian [wrote]. And then —this is a complex situation because of the fact that it's being made with Netflix — it kind of stretches the length. In other words, I'm not sure if it had to be, for example, a two hour and ten-minute movie. Or could I have been at four hours?

QT: Right, yeah.

MS: I'm not certain as to the ultimate venue, so I made it pure in my head in a sense like, "What if it's just a movie? What if it's got to be as long as we feel or as short as we feel?"And, because the nature of the characters — basically, one character is telling the story in flashback at the age of 81.

And when you get to my age, Quentin — and you get a little slower, a little more contemplative and meditative — it's all about thinking of the past and about [the characters'] perception of the past and so, by the third shot in the picture,

I felt it in the editing. And I said, "Let's see where it takes us and play to a few audiences and see how they tolerate it or not."

So we kept saying, "We should try this and that." And also the nature of the computer-generated stuff we were doing gave us a certain pace.

Our Reaction:

We know that the rise of streaming has changed the way television works, but we forget film is affected too. Scorsese has never been afraid of making long movies. The Wolf and Wall Street and Silence both clock in around three hours long, but it's interesting to see him make a movie with no worry about taking his time because he was not sure where it would live.

I like framing this as an audience test, too. Both these filmmakers are aware that work only survives if the audience embraces it. While I think Tarantino is more of an auteur opening us to the world the way he sees it, I like knowing Scorsese is still trying to entertain us. But I also like knowing he's matured.

On movies about Hollywood

MS: The first film I saw about Hollywood was [Billy Wilder's] Sunset Boulevard.

QT: Right, yeah. [laughing] Very dark view of Hollywood.

MS: And so in a sense, they were codified—the truth was coming through a different code, and a different culture in a way. And it didn't make them any less [important] from the European films I saw. But there was something that affected me when I saw those Italian films on that small screen that I never got past, and so that changed everything.

That really gave me a view of the world, the foreign films. It made me curious about the rest of the world, apart from the Italian-American Sicilian community I was living in.

QT: So did it even open you up to New York, in a way — reaching those other cinemas, going outside of your neighborhood, searching out those places?

MS: It was more than that. Because it was really going into America, outside of the little village that I grew up in.

QT: Oh, yeah, I get you.

Our reaction:

With so much access in our world, it's hard to imagine growing up without movies from everywhere. Hearing how Scorsese broadened his horizons as a kid made me wish we had more services that highlighted Classic, Criterion movies, or foreign films.

Hopefully, one of these streamers will see the value in this kind of programming and add them to their catalog so they become accessible to the next generation.

On the ending of Taxi Driver

QT: So my question, inTaxi Driver, it's like -- I'm sure the reason the movie, when it came to actually getting made (at Columbia) because it is vaguely similar enough to Death Wish…

MS: (Producers) Michael and Julia Phillips, who had just won the Academy Award for The Sting, were really pushing the picture and working with the people at Columbia — at that time it was David Begelman — and they got it made. But [the studio] did not want to make it, and they made it very clear every minute.

QT: Oh, really. [laughing]

MS: Every day. And especially when I showed it to them, they got furious, and [it] also got an "X" rating. And I always tell the story that I had a meeting with Julia and myself and the Columbia brass. They looked at me. I walked in, ready to take notes. They said, "Cut the film for an R or we cut it. Now, leave."

QT: Jesus!

MS: I had no power at all. There's nothing I could do. I came up against a monolith, and the only people who were able to pull it through were Julia and Michael. But meetings, talks, and then, of course, dealing with the MPAA to shave and trim a bit here and there. Again, because, in doing the shootout, I didn't know how else to present it. Maybe knowing that some of it was artifice, I didn't realize the impact of the imagery. So I cut two frames and walked out. I mean, the violence, it's catharsis, it's so true. I felt it when I saw The Wild Bunch.

QT: Well, that's an interesting thing. For instance, I feel a catharsis at the end of Taxi Driver.

Our reaction:

Hearing Tarantino and Scorsese talk about cathartic violence is grand. Both these men have dealt with blood and guts in different tones across their careers. Honestly, the cuts to Taxi Driver must have been negligible because so much is still in that movie.

I also like hearing about fights they had with the studio. It's great knowing these cinema icons also had to break in just like anyone else.

On referencing other Directors in their work:

QT: From time to time, if I'm in a really cool cinema bookstore, I like picking up a critical essay book on a director that I haven't watched their films that much. And I'll just kind of start reading about them and that will lead me down the road to another filmmaker's work. And so I was in Paris for our one weekend of shooting in France for Inglourious Basterds, and they had this wonderful cinema bookstore by Rue Champollion, where all the little cinemas are, and I hadn't watched a lot of Josef von Sternberg's movies. So I picked up one book about him and I liked it so much I got another book. I eventually got his autobiography, which I thought was hysterical. I don't believe a word of it, but it's very funny.

MS: [Laughing] I know, I know.

QT: Not a word. So I started watching some of his movies, and I was actually kind of inspired by his art direction.

MS: Yes.

QT: So I started, and now I do it at least a couple of times per movie, but on Inglourious Basterds, it was set up to do this Josef von Sternberg shot where you take all of the art direction and put it in front of the camera. And you dolly shot through the art direction as you follow your lead character — all the candles and the glasses and the clocks and the lights and just create one big line and then put a track line in there and then have your character go like this. So that is officially a Josef von Sternberg shot.

MS: I have a thing with tracking parallel to the action — just tracking it, like four people are standing there. Instead of tracking this way, it just goes straight this way and I think it comes from… there's a scene in Vivre sa vie where the guy says, "I want a Judy Garland record," and she goes across the record store to find the record and then the camera just comes back with her. There's an objectivity to it that is like a piece of music really, like choreography, but also the objectivity of this, I should say the state of their souls in a way — it doesn't want to get too close.

QT: Yeah.

MS: But the one I really tried to — I tried to capture it in many films. I can't do it, but it doesn't matter. It's the fun of doing it. There's one shot in (Hitchcock's) Marnie where she's about to shoot her horse. And it's an insert. And it's her hand with a gun and the camera is on her shoulder and it's running. The camera is moving with her and the ground is going this way and I've done it in practically every picture. There's something, the inevitability of that that she hasn't — somehow it looks [like] I've put the actor on dollies…

QT: Yeah.

MS: The camera floating up. I'll never get it right because Hitchcock did it. But it's so much fun to do.

Our reaction:

If you're like me, you probably find yourself referencing Scorsese and Tarantino in every single general meeting you take.

As we work on our own projects, it's hard to define your style while emulating others. I feel a sense of calm now knowing that style comes with experience. And that even these two masters try to snag shots they saw other people pull off.

What are some shots your try to pull off in your films?

On finding the right actors:

QT: I'm always curious, especially when it comes to filmmakers whose work I've studied, you hear about different iterations that could have happened with [one of] their movies. That brings me to [an aspect of] Mean Streets that I've never heard you talk about, when you went to Warner Bros. to do it and the period of time that Jon Voight was going to play Charlie. Will you explain how it didn't happen?

MS: Well, it's a delicate issue because, around that time, I got to know Jon Voight in Los Angeles a little. Harvey Keitel, all of us together, and it was constantly, "What if so-and-so's in it? Maybe we can get financing. What about this? What about that?" And Voight was a wonderful actor and so we talked about it for quite a while. And he was really thinking about it. I went to his class one night and there I found Richard Romanus and David Proval and cast them [in Mean Streets] from his class. And then, you know, I spoke to Harvey about it because it was written for Harvey.

QT: Yeah, yeah.

MS: And Harvey told me, "Look, you've got to get the film made. And I understand, maybe if he does Charlie, I could do, you know, Johnny or whatever." We were working out something. And I said, "You understand that I've got to get this made." And even Barry Primus, we were talking about Barry doing it. And it was a matter of getting the financing, really. Damn good actors. And the night came finally when I had to shoot some background shots for the San Gennaro Feast, and we were based on the corner of Umberto's Clam House, where Joey Gallo had been killed six months earlier. And I was on a roof, I remember, and I was about to put a coat on Harvey and go in and shoot. But they said, "You know, Jon wants to talk to you one more time," Jon Voight. So I went downstairs to make a phone call and he said, "I'm really sorry. I just can't do it." I said, "OK." I thanked him, hung up. I went up to the roof, I said, "Put the coat on. Let's go. It was written for you, and that's the way God has worked out."

QT: I had another story like that. I make Reservoir Dogs and I'm making a movie for Live Entertainment, which was the video arm of Carolco at that time.

MS: Oh, God, yes.

QT: And so it was like, we're not even guaranteed a theatrical release. It's like, well, "If it's really good, we'll release it. We'll see." So I'm ready to lock picture and Ronna Wallace, who was the head of the company—I had been kind of working with her No. 2 guy, which was Richard Gladstein—she was just like, "Well, these guys have been working really hard to get it ready for Sundance so let's not lock yet. And she's actually trying to be nice, like maybe I need another week or something. No, I don't need another week so it doesn't seem so nice. I went to lock. But she says, "Send a print to New York. I want to watch it." So we sent the print to New York, and she comes walking into the screening room with Abel Ferrara. And so Sally Menke, my editor, was like, "Oh my God, they're going to take the movie away from Quentin…"

MS: That's where they hit you, yes.

Our reaction:

So much of filmmaking is kismet and necessity, that includes casting. You can look all over for people who are hot and will greenlight the film, and you can stumble upon the people who become hot later after you give them a chance. The key is to find a balance. The best thing you can have is a "go" movie.

So devote your resources into giving the studio who they want but keep your eyes open for who else could be out there.

What's next? Lessons from Scorsese for Filmmakers!

Oscar-winning director Martin Scorsese has made his mark on filmmaking with a career that stretches across 50 years and multiple genres.

Learn from his experiences!