Music to a Director's Ears: Pro Tips from 'Ted Bundy' Composer Ariel Marx

Sought after composer Ariel Marx shares tips for directors and talks about her motivation for Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer.

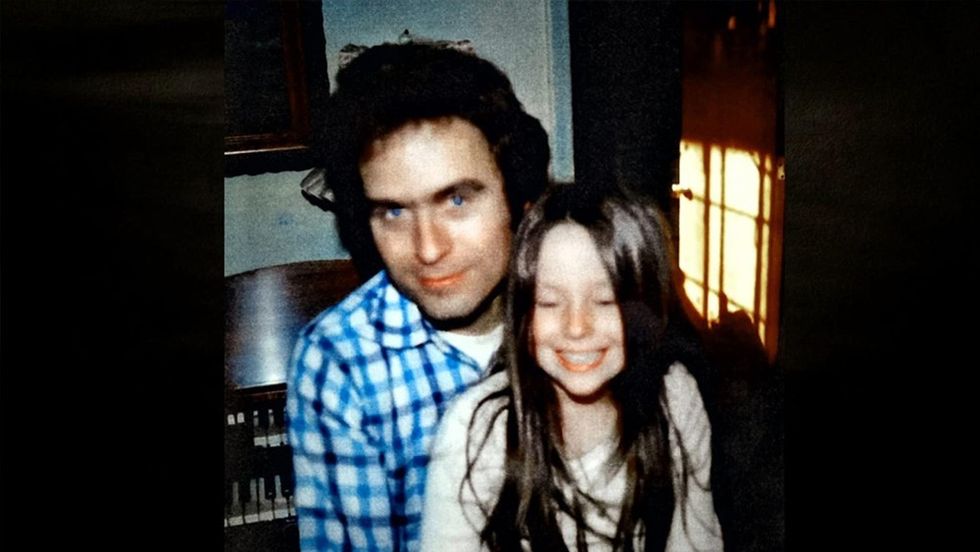

When it comes to composers, Ariel Marx is as busy as they come. The award-winning multi-instrumentalist has a natural intuition when it comes to aurally supporting the emotion of a story. So when she was approached about Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer, a 5-part documentary that details the serial killer through the eyes of his longtime girlfriend Elizabeth Kendall and her daughter Molly, the musician knew the score couldn't be akin to any other true crime story. It had to be unique yet still visceral.

Marx sat down with No Film School to talk about how she weaved a score that manipulates harmonics and string instruments to propel perspective and convey emotion.

NFS: If a director doesn’t have a vast knowledge of musical language or terminology, how can they communicate what they are looking for in a score?

Ariel Marx: Sometimes first-time directors can feel intimidated if they don’t have musical knowledge, but I don’t think it’s a requirement. For me, it’s all about communicating the emotion and supporting the aesthetic vision of the story.

I know music can be the furthest away when comparing it to cinematography or editing, but that shouldn’t get in the way. My job is to support the narrative through music. So, it’s often more clear when you start talking about the story in terms of narrative. For instance, you want it to feel somber. To feel provocative. To feel mysterious. Then we can feel our way into the music after that.

NFS: So, that initial conversation is important?

Marx: Yes. It’s kind of like calibrating to get on the same page of these basic blocks. Even mixers and engineers have different vocabulary for what muddy is or what tinny is. Yes, there are frequency parameters, but we are all so partial to our own taste.

NFS: True. Someone's version of what dark is is going to be different than someone else's.

Marx: Exactly. Words like bright or dark can still be applied in terms or techniques. Bright generally means tinnier or higher, and darker, is of course, lower and muddier. But sometimes it’s not always literal though. From person to person, it’s going to take some back and forth to get on the same page.

Marx: I have had the pleasure of working with people in the script stage. That saves a lot of time because you have all this time in preproduction to think about the music. You can work on palette tests and develop a little bit of the language for the score.

But generally, it’s all over the board, and as composers, we do figure it out in the time we are given. I would generally say 3-4 months is nice to have in terms of getting on the same page, going through all the cues, and then recording everything. But I’ve done projects with way less time.

NFS: Is it better for a director to have an idea for the theme or let the composer explore?

Marx: If a director has a strong idea for the score, I think that’s wonderful. That’s clarity. That’s leadership. That’s a vision for something. Whether we end up using that or not, it’s always valuable to have that initial instinct. But from trial and error, we might end up in a totally different direction—though I wouldn’t say it’s creatively prohibitive.

NFS: What about editors using temp tracks? What side of the fence are you on with that?

Marx: People feel really different about this. I’m one of those composers who really doesn’t mind temp. I think it’s an easy way to have conversations about music. I think temp is great for quickly zoning in on likes, dislikes, palettes, instruments, and textures they love. I don’t think it harms the process and it’s just another level of information that can be useful as long as there’s an understanding that the score has to be its own voice.

NFS: With Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer, did director Trish Woods come with an initial idea?

Marx: She did have a strong vision. I initially spoke with the music supervisor Jody Colero. He sent me the look book and there was a page in there about the music and the song for the credits.

When I talked to Trish, her idea was to have an entirely new take on the Ted Bundy story. Rather than focusing on psychoanalyzing him, it was more about the trauma he had caused to these families and women. And more specifically, through the lens of his ex-girlfriend Elizabeth Kendall.

NFS: That is different. How did it affect the emotional tone?

Marx: Trish didn’t want the music to push the fear or to be menacing. It’s easy with true crime to forget that these are real lives and real trauma. She wanted the music to have empathy. To have humanness and to focus on the sadness and growth rather than the fear of Ted Bundy.

NFS: How did that translate for the score?

Marx: We decided on more a classical palette using string instruments. This would give it the right amount of warmth, propulsion, depth, and darkness. Also having a palette that was organic and visceral was very important.

In terms of notes, especially in the first episode, it’s very much about Elizabeth as a woman and a single mother meeting a man and falling in love. It’s her telling her story and truth of her experience. The music had to be honest about her love for him instead of foreshadowing the man he becomes.

NFS: It’s just not the instruments you choose but how you play them. Did you do anything unique for Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer?

Marx: A few. I stayed in the lower range of the string section like bass and cello. I used extended techniques where it doesn’t sound like a clean bow, but it’s dragged a little too hard or too soft. I also used harmonic techniques where instead of it sounding like a string heard in a concert hall, it’s more textural and it hits you in the gut.

Other times with lower instrumentation the pitch is a little more unclear. It becomes more of a sound world than a single string. I used that approach a lot for her memories of Ted or for the quieter moments.

NFS: Let me get you out on this. When a director doesn’t like a piece of music, what’s the best way to get on the same page?

Marx: There are going to be things that are not liked in the creative process. But it’s about having that clear shorthand—that communication that allows you to pull things apart and listen to it together. As a composer, you ask if there is something specific a director is not responding to. Is it a bigger tonal issue? Is it too sad? Is it not fast enough? Does it not have enough energy?

Then you can dive into more diagnostic things like does an instrument range need to be lower or is there a certain sound rubbing you. Sometimes it’s a smaller, simple trick that can make a cue completely different. It’s all about listening together and finding out what’s not working.