'Lolita' and The Art of Adaptation: Lessons from the Masters

Filmmakers looking to adapt a work of fiction to the screen can take notes from these classic examples of the art.

The greatest adaptor in history would have to be Shakespeare, none of whose plays were derived from original scenarios. Hamlet, for instance, takes its plot from no less than four sources, including an Icelandic saga from the 13th century and the Roman legend of Lucius Junius Brutus. Of course, it was Shakespeare's genius to take these myths and ancient sagas and translate them to the form of the Elizabethan stage.

And, in turn, almost all of Shakespeare's plays have made it to the big screen. Hamlet alone has been adapted more than 50 times, with one of the finest being Laurence Olivier's 1948 version.

With the ascent of film, the landscape of drama and literature were changed forever. As Daniel J. Boorstin, the critic and sociologist, wrote in his classic book, The Image: "For the first time, you could dramatize any scene from a novel. The grander the expanses of scenery, the more violent and wide-sweeping the action, the more rapid the change of scene...the more appealing was the story for movie purposes."

But similarities between the two media existed even before the advent of cinema. As Joseph Conrad, whose Heart of Darkness was later (quite loosely) adapted by Francis Ford Coppola into the Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now, wrote presciently: "My task which I am trying to achieve is, by the powers of the written word...to make to see."

But how does a filmmaker turn a literary work into a film? What qualities must a novel (or play) have to make a great cinematic experience?

Know what to cut and what to embellish

Curiously enough, the adaptation of a play into a film can present some of the greatest problems for a filmmaker, despite being an ostensibly dramatic work. A play, as it is written, is a work made out of words, of speech. Referring back to Hamlet, there is also always the question of length: while a film generally runs for an average of 2 hours, give or take, a theatrical production of Hamlet can run up to 4 hours, and consequently, great portions must be excised for the screen.

Jumping forward several centuries, one of the most successful modern adaptations of a stage play to the screen is arguably David Mamet's reworking of his own Glengarry Glen Ross into a screenplay directed by James Foley. But how did they do it? As Anthony Viera points out: "The spine is identical from stage to screen: a group of real estate salesmen turn on each other and themselves while scrambling to keep their jobs. Then, during the night, someone breaks into the office and steals the Glengarry leads, brand new sales leads coveted by the lower-tier men." But unlike a play, which is confined to actors talking on a stage, Glengarry the movie never feels less than cinematic.

"The spine is identical from stage to screen: a group of real estate salesmen turn on each other and themselves while scrambling to keep their jobs."

To achieve this, Director Foley uses lighting (an array of reds and blues), and Mamet restructures his play, crucially adding the character known in the screenplay as Baker, played by Alec Baldwin. Baldwin's profanity-filled monologue (absent from the play) serves as a focal point for the film, and has, according to Viera, even been screened for animation students as an object lesson in the way that a character's posture can connote authority. Watch the way camera angles, lighting and Baldwin's performance come together to move the action of the stage to the screen:

Baldwin's performance is so powerful that it has been referenced in several other films, e.g. Boiler Room, in a scene where amateur stock-swindler Giovanni Ribisi is told to watch the scene for pointers on how "to act." Mamet's addition, and Foley's direction, are excellent examples of how a playwright and director can collaborate to take a play consisting of talking heads and turn it into a cinematic classic.

Translate words into cinematic language

We think of the traditional, narrative cinema as being constructed from disparate pieces of film, strung together to present an illusion of temporal and spatial continuity. This is accomplished through continuity editing, also known as "invisible editing," a cutting style used to tell a story with a beginning, middle and end. Critic and essayist David Bordwell argues that there are three levels of cinematic narrative: the story world, comprised of the characters, their circumstances, and the setting. Below this we find the plot structure, being the arrangement of the events of the story which effect the characters, circumstances and setting of the first level. And finally, there is the narrative, i.e. "the moment-by-moment flow of information about the story world."

The task of the screenwriter and director, in adapting a novel or other written work, is to transduce the language of fiction into the language of cinema.

Bordwell's cinematic narrative, I would argue, is akin to the concept of voice as understood in fiction. Just like films, fiction at its best contains rich layers of subtext. The words of a novel or story present an action unfolding in time; these words that transmit the events of a story, the diagesis, are the written equivalent of cinema's invisible editing, and therefore akin to Bordwell's story world and plot structure: On the uppermost level, a sentence communicates information using, at the very least a noun and a verb. But it's only through the point of view of the story, (i.e, first person or third, omniscient or limited, etc.) and the way that its words are set down, that the reader can infer tone; attitude; as well as intangibles such as the reliability of the narrator, or lack thereof.

In fiction, as in film, there is always a sort of stylistic lack of reality, even in "realistic" works. In How Fiction Works, critic James Wood notes that, "...artifice lies in the selection of detail..." and that realism is both "lifelike and artificial." The same could be said of motion pictures, and so the task of the screenwriter and director, in adapting a novel or other written work, is to transduce the language of fiction into the language of cinema; this is most effectively accomplished, it seems, by taking the elements of the written narrative and discovering analogs within the language of cinema, i.e., camera angle, focal length, lighting schema, cutting style, and mise-en-scène.

"If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed."

Lolita: A case study in adaptation

In the book, Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist's Maze, Thomas Allen Nelson posits: "The right novel provided Kubrick...with a framework of action and character...within which he could integrate his own formal and psychological ideas." This process helped the filmmaker to do what is necessary to adapt a novel for the screen, that is, "create a tension between exterior and interior forms."

Starting with his third feature film, The Killing, Stanley Kubrick began to use novels as source material for his films. He would continue to do so, in one way or another, for the rest of his career. One of the most interesting examples in his corpus of adaptation is the reworking of Vladimir Nabokov's controversial novel Lolita, originally published in 1955. Whereas Kubrick's previous adaptations, The Killing (based on the novel Clean Break by Lionel White) and Paths of Glory (based upon the 1935 Humphrey Cobb novel) had focused on third-person narratives, Lolita attempts an altogether more impressionistic approach.

At the outset of the project, Nabokov spent six months working on a screenplay version of his novel: in the book (and this is a vast oversimplification), the narrator, Humbert Humbert, is infatuated with Lolita, a 12-year-old girl (15 in the film) whom he essentially kidnaps. Nabokov's use of a first person, witty, pleading voice subversively garners sympathy for the protagonist, who is, in the end, just a self-serving pedophile, though this unpleasant truth is buried by the author so that the reader only comes to an apprehension of their own culpability (through identification) at the novel's end; because readers (and viewers) tend to identify with the protagonists of novels and films, and because the novel is told in the first-person, it's almost impossible not to feel some degree of sympathy for Humbert. But there is another voice present, that of a third person, who intrudes and undercuts Humbert's statements.

What this adaptation of a famous novel does, then, is what every good adaptation should aspire to. That is, it maintains the spirit of the source material without being in thrall to it, and creates, from fiction, a rich and cinematic experience.

Nabokov's first draft of the screenplay was 400 pages, and considerably more theatrical than the final, filmed draft. According to Nelson, "the screenplay has the camera gliding around..."; at one point, "it 'locates the drug addict's implementa on a bedside chair, and with a shudder withdraws." Kubrick, however, eschewed this approach in his first attempt at translating a first-person narrative to the screen; his methods were "far more covert" and altogether more cinematic (nb: the screenplay is, in the film, credited to Nabokov).

Kubrick pruned much of the beginning of Nabokov's novel, and begins the film in medias res, near the end of the story, with an original scene that creates a framing device; this framing acts as an analogue to Nabokov's third-person intrusions, as well as a means to spark cinematic interest in the viewer, a creature less apt than a reader to put up with much exposition (after all, this is a movie, so it's incumbent to cut to the chase, etc.) The framing device is, partly, Kubrick's cinematic way of both undercutting Humbert while also establishing a cinematic tone of paranoia and dread that will come to dominate the film.

In Kubrick's previous adaptations, the point of view was exterior, with the drama coming from an activity being performed (a heist in The Killing, the general slaughter of WWI in Paths of Glory). Here, the landscape is far more internal and psychological. The performances in the film are uniformly excellent, especially Peter Sellers' performance as (among others) Humbert's nemesis Clare Quilty. In the novel, Quilty has a far smaller role; in an interview with writer and sometime collaborator Terry Southern, Kubrick explained his decision to give Quilty a much larger presence in the film: "just beneath the surface of the story [the novel] was this strong secondary narrative thread possible—because after Humbert seduces her in the motel, or rather after she seduces him, the big question has been answered—so it was good to have this narrative of mystery continuing after the seduction."

As he would do in Dr. Strangelove, Kubrick makes use of Sellers' ability to disappear into multiple roles, only here, Sellers is playing Quility, and Quilty is playing a psychiatrist (that is, wearing a disguise), a psychiatrist whose sole mission is to torment Humbert, his rival for Lolita's affection, and in many ways, his double (a favorite theme of Kubrick's that the director perhaps saw in Nabokov's novel and expanded.) What this adaptation of a famous novel does, then, is what every good adaptation should aspire to. That is, it maintains the spirit of the source material without being in thrall to it, and creates, from fiction, a rich and cinematic experience.

Just like Mamet, Kubrick doesn't hesitate to alter the text, and his rich use of mise-en-scène and performance (Nelson notes how Sellers embodies Nabakov's verbal wit in his performance; without him, the film would undoubtedly be a different, and weaker, beast) turn the written word into images that express the ideas at the heart of the story.

The art of adaptation is a daunting and almost ridiculously complex endeavor, and this brief survey can only hope to get at the subject in a glancing manner. Perhaps the most important takeaway for a filmmaker would be that, when making the transition from a written work to a film, the utmost care must be taken to isolate those elements of the narrative that are, in essence, 'unfilmmable', and then transform them into a scene. This is, no doubt, a tall order, but the best adaptations, as we've seen, have managed this feat with seeming ease. Kubrick himself once remarked, "If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed." If this is true, and I think it is, then it's incumbent on the screenwriter or filmmaker who is attempting an adaptation to take not only the plot of a given work, but its subtext, its 'meaning,' and via a sort of aesthetic alchemy turn the written words of a work of fiction into the sound and vision of film.

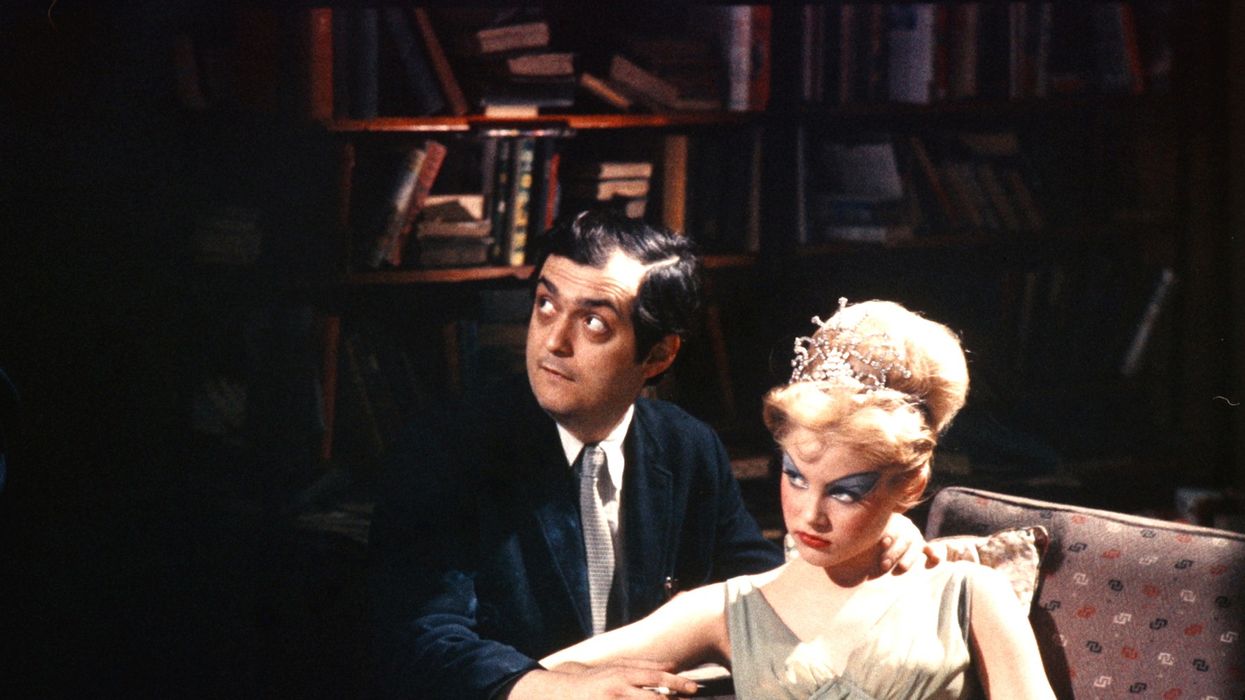

Featured image: Stanley Kubrick on the set of 'Lolita'