'Don't Swallow My Heart, Alligator Girl!': Felipe Bragança on Why You Should Write Your First Draft Like Poetry

Felipe Bragança's 'Don't Swallow My Heart, Alligator Girl!' is a magical-surrealist film that takes your favorite '80s classics and reimagines them.

When filmmakers Felipe Bragança and Marina Meliande were growing up in a post-state-sponsored-cinema Brazil, the biggest import of pop culture was American movies. Bragança's debut film, which Meliande produced, is a story as South American as it gets: a 13-year-old Brazilian boy falls in love with a Paraguayan girl in a town soaked with centuries of bloodshed. But by conjuring the imagery of 1980s American movies, the film takes on a magical realism that leaves you wondering whether it is, in fact, a specter of the point-of-view of the generation who grew up on those movies.

With poetic tone, exuberant visuals, and the creative interpretation of conflict, Don't Swallow My Heart, Alligator Girl! is something of a masterpiece.

"When you close your eyes, you have to continue seeing your movie."

Bragança and Meliande sat down with No Film School prior to the film's Berlin premiere to talk about adapting the script from two short stories, reinterpreting American pop-culture imports, and being stubborn enough to build a film industry from the ground up.

No Film School: Don’t Swallow My Heart, Alligator Girl! is steeped in the real history of violence between a Paraguay-Brazil border town, but reimagined in a style of magical realism. How did you come up with the world of the story?

Felipe Bragança: The script was based on two short stories from the Brazilian writer Joca Reiners Terron. The stories are really short, like two or three pages. His writing is about his sensations and dreamy memories growing up in this violent border region in the 1980s. The narrative I created in the script started from his first story about this platonic love with an older girl. I put myself inside the two pages and started to work within this atmosphere. Everything is a little bit magical. For me, it’s just these teenage hearts trying to understand the world.

"It's a mix of reality and the projection of ideas from the '80s movies we grew up on."

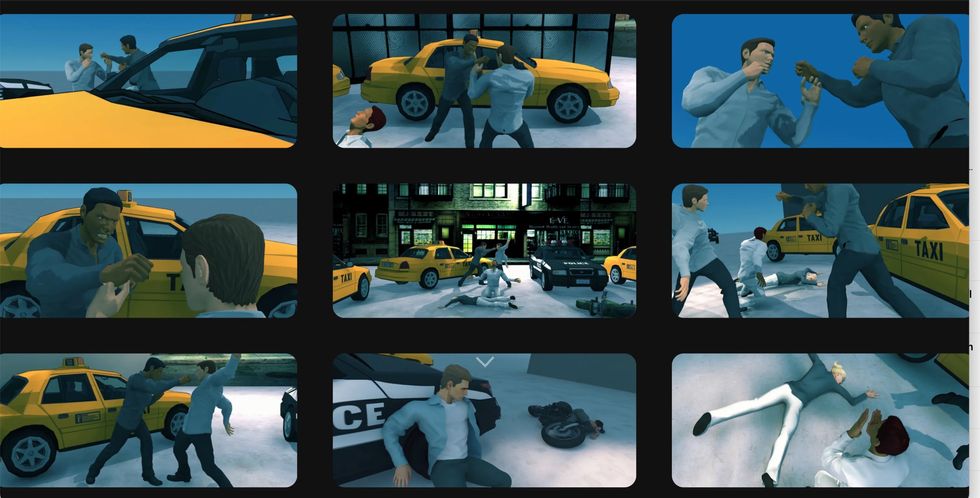

Jorge’s second short story is about this mythological motorcycle gang. It has the same point of view: the writer is a young boy talking about his older brother’s gang. All the representations of the gang are channeled through the eyes of a young boy. In some ways, it’s a mix of reality, and the projection of ideas from the '80s movies we grew up on. I like to say that the character of Telecath [the leader of the motorcycle gang] probably watched the film The Warriors when he was in his 20’s. Now he’s, like, 40-something and he created a gang, and his reference would have been that film.

Marina Meliande: The kind of films we love making deal with genres—trying to mix different genres in order to build something else.

Bragança: As a Latin American filmmaker in my generation, we all grew up watching American genre movies and TV. Sometimes, art house films try to deny this influence. Instead, I like to create something new from it. All the characters in Don’t Swallow My Heart Alligator Girl are, in one way or another, projecting something learned from TV that was imported from the U.S.

We are creating something with this history of cultural import and using our imagination to go beyond it. It’s always poetic in some way when people say, "Oh, you’re Brazilian, you should do something more Brazilian. Why are you referencing The Warriors?" Because all filmmakers my age saw this film and probably loved it! We grew up on it. We are in an era where we received all this pop culture from the U.S. and instead of denying it, we should use it. We say, "You’ve sent us all this pop culture, and now we are going to take your symbols and music and reconstruct them into something new."

"I start from the poetry, then in the second draft, I start to look for the narrative."

NFS: How did you go from these super short stories to a script? In particular, how did you keep that magical tone, without getting bogged down by the small details?

Bragança: I write the first version of the script really fast. The first version is about getting down the poetry that I feel about the story. It isn’t a complete story line yet, just maybe a script of 40 pages. I start from the poetry, then in the second draft, I start to look for the narrative. Rather than starting with the literal, physical connections, the first version is like music.

NFS: When working with your DP, how did you create the look and feel for the film?

Bragança: I knew the film was not going to feel like a contemporary realistic film. I was working with a DP from the south of the country, Glauco Firpo. It was the first time I worked with him, but I knew he could create a really beautiful atmosphere with minimal equipment. I told him, "This is going to be a fiction, it’s going to be on the border, it’s going to be big, and it is not realism.” We started with classic filmography from the 1980s. We were always drawing and finding the colors.

The production designer and costume designer were very important in achieving the tone. I spent four years going to this border town, so my script was specific to this place. However, it required more—from the jackets of the motorcycle gang, to every little detail, to complete the world.

"I think of the first version [of my script] like music."

Meliande: Sometimes we were in real homes and would just add a few touches. We didn’t want to come in as foreigners and destroy everything. We like to be more respectful to these people and make them part of the movie.

Bragança: It’s like turning the volume a little higher. We take the original elements and saturate them, turn the dial up. The cinematography was the same. The idea was not to create a surrealistic fake light, but to use real light and create something just a little enhanced. Turn the volume a little bit higher.

NFS: Decades ago, Brazil had a thriving film history. What’s going on now?

Bragança: Brazil is a huge country, the size of the United States, with all kinds of regional cinemas. But the big industry, because of TV, is in Rio and Sao Paulo. However, I think there is a generation of filmmakers who started studying cinema in 2000-something, who started to understand that you could create something new that the industry was not doing. There’s a movement going on that I think you see with more Brazilian national cinemas starting again.

We were in a dictatorship to the end of the '80s. At that time, films were made with the state's money. A lot of interesting films were made, in the dictatorship, inside the state, controlled by the state. Filmmakers found ways to write something that looked simple to get state approval. They wrote erotic stories to say, "Here's a popular film!" But it would really be a veiled political thing.

"It's like turning the volume a little higher. We take the original elements and saturate them."

Then, in the 1990s, when the dictatorship finished, thanks to the people who fought against it, this big state production company tradition was dissolved. For 10 or 15 years, there was no Brazilian film. The idea was, unfortunately, if something is bad, you just destroy everything—like Trump-style. You find something that you think is a problem, and instead of fixing it, you destroy it. I think we are in some way we are lucky to be completely reconstructing the film industry over the last 10 years.

NFS: What would be your best piece of advice for filmmakers?

Meliande: It’s very important to put the right people together. It’s a dream that we made this film together with friends and people who became our friends. Sometimes, when you get 10 or 15 people, or 100 people together, you have to keep them and dream higher together.

Bragança: You have to be stubborn like crazy. When you close your eyes, you have to continue seeing your movie. I say that I know I'm ready to make a movie when I close my eyes and I can hear the sound of the movie. If you can hear the atmosphere—describe the sounds inside the movie—you are ready.