How a Filmmaker Cracked Open David Lynch's Mind

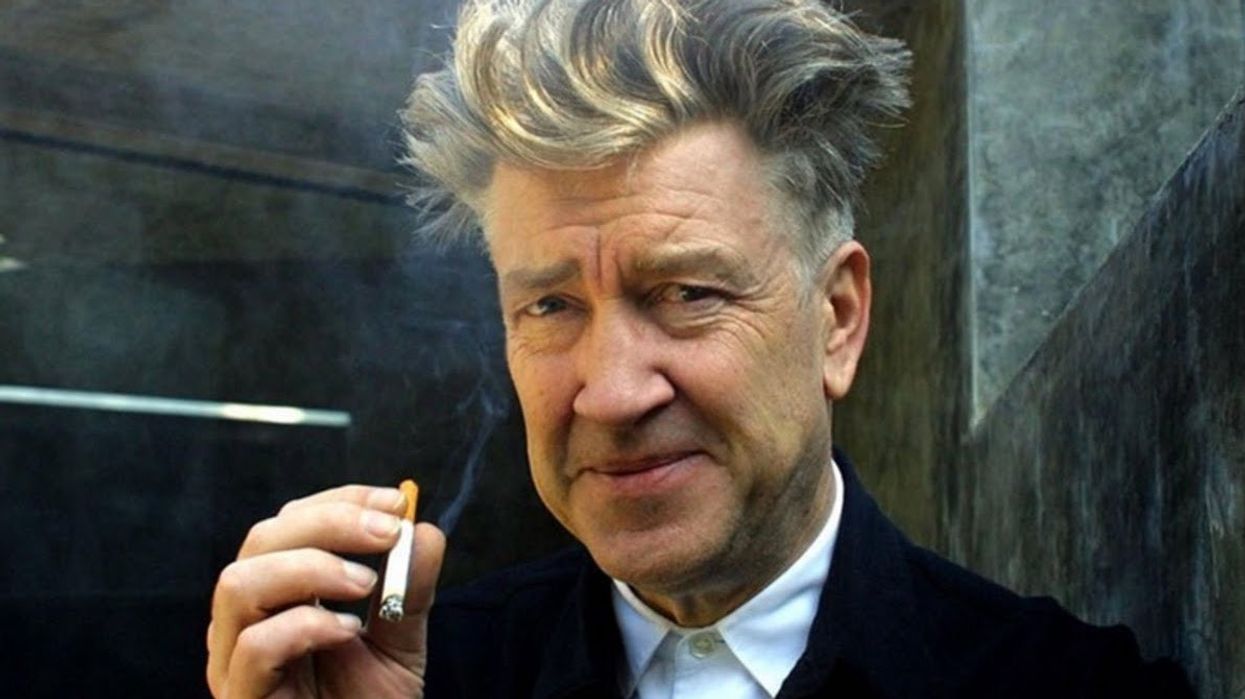

Jon Nguyen's 'David Lynch: The Art Life' digs deep into the enigmatic persona of David Lynch.

A five-year-old boy is sitting in the driveway of his parents' suburban home when a strange woman—naked, hysterically weeping, and bleeding from the mouth—burths forth from the surrounding woods. No, this is not a scene from Blue Velvet (although he would later recreate it in the film); it's a memory, and it belongs to none other than David Lynch.

"It was otherworldly," Lynch says of the incident in a new documentary David Lynch: The Art Life, about his childhood, adolescence, and young adult beginnings as a filmmaker and artist. "She came closer and closer, and my brother started to cry. Something was bad-wrong with her, and I don't know what happened, but she sat down on a curb crying."

Just in time for the Twin Peaks revival in May, David Lynch: The Art Life treats Lynch fans to a deep dive inside the enigmatic 70-year-old filmmaker's mind. Though usually cryptic about his private life and past, Lynch opened up to documentarians Jon Nguyen and Jason S., the latter having spent two years living alongside Lynch in his Los Angeles home.

Buried within Lynch's memories are kernels of inspiration for his surrealist life's work. They begin in Missoula, Montana, where Lynch describes his childhood world as having been "no bigger than a couple of blocks," spurring a fascination with small-town America. Lynch's mother, sensing her child's imaginative abilities, refused to give him coloring books, though she allowed her two other children to use them. "She thought they would be destructive and kill my creativity," Lynch says.

As a kid, Lynch's father instilled a DIY, project-based work ethic into his son. (It should come as no surprise that Mr. Lynch, a research scientist, was a bit eccentric—he refused to take public transportation to work, opting instead to walk there wearing a cowboy hat. "He was his own guy," Lynch says. "He didn’t give a shit.") Young David and his father would often examine insects together, a pastime that would later inspire Lynch to create Blue Velvet's opening sequence.

"My friend said, 'You're not going to fucking believe it. David agreed to let you make this film about him.'"

The Lynch family moved to Boise, Idaho, which Lynch remembers as "sunshine, green grass, mowed lawns—such a cheerful place." But, soon after, they relocated to Virginia, where "it seemed like always night" and the teenage David developed intestinal spasms. "It was total turmoil," he said. Thus began the filmmaker's obsession with the dark underbelly of everyday life. He began having "dark, fantastic dreams" and hanging out with the "bad bunch," getting into trouble. "I was living in hell," Lynch says of his early adolescence. He felt schizophrenic: he was one person while hanging out with his friends, and another entirely while acting on his creative impulses in his painting studio. Lynch's early paintings are reminiscent of Anselm Kiefer: neo-expressionist, often macabre, and deeply evocative.

As a young adult, Lynch moved to Philadelphia to attend art school, where he further cultivated his penchant for the morose. "Even though I lived in fear, it was thrilling to live the art life in Philadelphia at that time," he remembers. "There was thick fear in the air, a feeling of sickness and racial hatred." He describes the city in that time as a "weird town" where he had "crazy neighbors," including a woman who approached him on occasion squeezing her breasts and proclaiming that her nipples hurt. One night, Lynch convinced the night manager of the local morgue to let him in. "You wonder the story of each one," Lynch said of the experience. "It makes you think of stories."

After Lynch hallucinated one day that his painting was "moving, with sound," he took an interest in filmmaking. He made his Philadelphia home, which he shared with his girlfriend and fellow art student, into a veritable laboratory, where he conducted experiments on decomposing objects and animals to film. When his father visited, David showed him the basement, where he housed his in-progress experiments. His father was thoroughly spooked. He said to young David perhaps the most haunting thing a parent can ever say to a child: "Dave? I don't think you should ever have children." Although Peggy, David's wife, was already pregnant at the time, the remark never left David's consciousness.

Several years later, with a young child and a wife, Lynch's parents urged him to give up filmmaking for the sake of his family. And he almost did. Were it not for a grant from the American Film Institute—"a total life-changing phone call"—Lynch might have thrown in the towel. "I don’t know what would have happened if I hadn’t gotten that grant," he admits. "I really don't."

No Film School sat down with Nguyen to discuss how he convinced Lynch to participate in the film, how he created a "Lynchian" mise-en-scène, and more.

No Film School: What is your background?

Nguyen: Well, I've been making films for the last 10 years. I was a casting assistant on The Beach, the Leonardo DiCaprio film back in '99. I produced Lynch, the documentary during the making of Inland Empire, in 2006. For this film, I get to helm it as director.

NFS: Being in the industry in different capacities for so long, what did you think of directing for the first time?

Nguyen: Well, I really like this role because you get to work with so many specialized people, like the sound designer or the composer or the editor. On this film, they were very experienced and they've all gone to film school. I'm the only one that didn't go to film school. Of course, I surrounded myself with people that knew what they were doing. It was great to get all that support and input from them.

NFS: David is an elusive character. Over the years, I'm sure many people have wanted to make some version of this film. How did you convince David to let you make it?

Nguyen: Well, I was bold enough to ask him. Really—I just remember I called up my friend, who was David's personal assistant on production during Mulholland Drive. I said, "Do me a favor. Ask David if I could make a film about him." He laughed at me and he was like, "No way. David is never going to agree. He's very private." I just was like, "Could you just ask? Just see what he says." I said that thinking that he was going to say no.

My friend called me back up a couple days later and was like, "You're not going to fucking believe it. David agreed to let you make this film about him."

NFS: Wow. So you didn't even know him at that point?

Nguyen: No. I didn't know him at that point. You always hear about these fashion models who are like, "Oh, I never get asked out on dates because everybody is too intimidated to ask." I think maybe people were too intimated with David. No one asked David to make a film about him. I don't why he said yes. Maybe because I was brave enough to ask him.

NFS: David is quite candid in this documentary, as opposed to the elliptical public persona he often presents. How was the process of getting him to open up?

Nguyen: In the beginning, when we started interviewing David, he had his arms crossed, smoking a cigarette, and we knew by the way he was answering—kind of very short answers—that he didn't want to be interviewed by us on camera. Finally, he was like, "Pick up the camera. Follow me. You'll know what the film is about when it's over."

That became Lynch One, the first documentary we ended up shooting. We had hundreds of hours' worth of material. I was a producer on that project. At the end of that project, the director and I were saying, "Man, we're getting to know David a lot better. I think if we wait a little while longer...." We just felt like he was getting ready to open up a little bit more.

"We weren't interviewing him Barbara Walters-style, because that's not how you would approach David."

So we waited and came back to him four years ago and asked him if we could make a different project, more about his personal life. He was kind of forced to sit down and be interviewed, to carry on conversations with us. It was almost the opposite of our first approach, where we were running around with a camera, following David, filming him. This time, we sat down with him.

NFS: What kind of questions did you ask him?

Nguyen: It was broader subjects. Jason S., the interviewer and DP, was living up at David's house for two and a half years. He would get a buzz on the intercom once a week and David would be like, "Come on up. I have some free time." That would happen when David was in the mood to talk. We focused on broad subjects, like, "Today, we're just going to talk about your mom." Through that engagement—kind of giving him the camera to talk about his mom—stories would come up.

Sometimes we got really great stories. Especially on the day we talked about his dad. We weren't interviewing him Barbara Walters-style, because that's not how you would approach David. It was more giving him room to talk—a conversation between him and Jason as opposed to an interview with a journalist.

NFS: I'm sure that would have felt more stilted to him.

Nguyen: Yeah, and our approach gave us a little bit more intimacy. That's what we were looking for: to catch him off guard. And the best way to catch him off guard was to not present it as so formal. It was like, "Oh, let's just sit and talk. Today, the subject is about your mom, but you can lead it whatever way you want." It was fascinating.

We would basically get a little back story; then, he would dive deeper and deeper into memory throughout the interview. Throughout the conversations, he'd dig up more stories.

NFS: It was incredible to me that he had such a vivid memory of his youth. He remembers specific things that people said. Conversations he had. Images he saw. He seems to have a photographic memory.

Nguyen: You know what? I thought the very same thing. Sometimes he would repeat stories years apart and it would be exact, down to the detail. I really believe it's because he's been mediating two times a day for the last 40 years. His brain is so clear. He does transcendental meditation two days a week. He hasn't missed a day since he began.

NFS: What was something surprising that unfolded throughout this process of getting to know David?

Nguyen: I always thought, "Oh, David being the master that he is, he was just born into [the film business]." The thing that surprised me was that he had to work so hard to get to where he was. He came to a certain point in his career where we could have lost him. If he didn't get that grant to make The Grandmother, which led to him being invited to LA to go to AFI and getting the opportunity to make Eraserhead....

When your parents say, "Hey, you have a kid. You've been working on this film for five years. Give up. You need to take care of your family. You're not a filmmaker yet. You're just struggling to make a film." Most people would have quit. Lucky for us, David was stubborn and he felt like he could never give it up. So many filmmakers give up their dreams because they have to put food on the table. They have to make a living. They get pressured from family and friends to give up the silly filmmaking. You're not making a living off of it. David had that same pressure. Lucky for the world of cinema, he didn't give into it.

NFS: Did you ever feel any similar pressure when you were making this film?

Nguyen: I didn't have that pressure because I do other things on the side and we had financing. It's a different world that filmmakers live in nowadays. We can edit on our computers. We could shoot cheaply on a Canon 5D and on an iPhone. I was living in Copenhagen and Jason was living up at David's house. He was able to send me material and I could download it instantly. During the interviews—halfway through—he would send me the material so far. I would listen to it real quick and be able to write questions for David and Jason would continue the conversation.

I remember on the first Lynch project [Lynch One, made during the production of Inland Empire], we had to hire a color grader and we spent so much money trying to get materials shipped back and forth, FedEx or whatever. I wasn't able to participate as a creative producer at that time. But this time, because of the internet, we were able to work remotely with each other. So we didn't have that pressure to give up because it freed up so much time so we could work on other things besides this documentary.

"It's a very pure Lynch documentary because we used all his ingredients."

NFS: Did you find that people wanted to help you get this movie made because you had such a powerful subject at the forefront?

Nguyen: I did the Kickstarter that we ran [for the film]. Filmmakers were writing me—Adam S. Goldberg, who does the Goldberg comedy show on ABC, wrote and was like, "David has such a big influence on me as a filmmaker." He wanted to contribute. Then, I got calls from other film people—so many people from so many different walks of life that said that David had had such a profound effect on them and their career, whether they became graphic designers or painters. People wanted to contribute something, whether it was $1,000 or $50. It was nice to be able to get that support from his fan base.

NFS: Your movie is very Lynchian. There's a pervasive sense of absurdity and surreality the editing and the sound design and the music. How did you re-create David's mise-en-scène ?

Nguyen: Well, everything in the film that you see, from his voice to his photographs to his 8mm films to his earlier art films, short films, and paintings...99% of the film is Lynch material. It's pure Lynch. Even a lot of the music in the film was made by David. Three of his songs are in the film. We worked with a composer that was huge Lynch fan. It's a very pure Lynch documentary because we used all his ingredients. I think only photos out of all the pictures that you saw in the film weren't given to us by him. Everything else came from his archives.

But we didn't want to imitate his style. We didn't want to create to something that would overshadow the story. Everything had to support David's narration, rather than distract from it.

NFS: What was the process of working with the archive material?

Nguyen: At first, when we sat down to do the film, we cut a radio show with no visuals at all. We thought if the story could live as his voice alone, then that would be the backbone of the film. Then, we started working on the visuals. We said, "Okay, let's see if we can match up any of his paintings to any of the stories." And at the same time, we were going, "Which family pictures would match up to stories very well?"

NFS: When I was watching the film, I kept thinking about how so much of what creates an artist is their feelings from childhood and adolescence. It all compounds into your identity, which you then use to create your art.

Nguyen: We start the film with a quote where David says, "Everything that you do in the past conjures and colors everything that you do." That was basically the thesis for the film. We knew that his personal stories were going to have a direct influence on his filmmaking.