'Intent to Destroy': What It's Like to Expose One of Hollywood's Most Horrifying Untold Stories

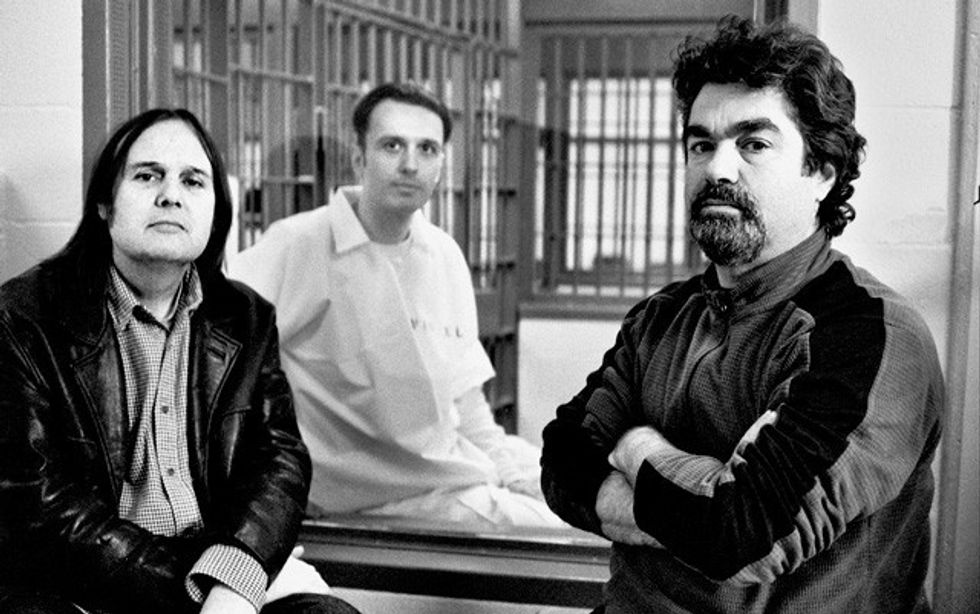

Joe Berlinger, a prolific documentarian, discusses 'Intent to Destroy,' his latest hot-button film.

Some say that the most groundbreaking movies Tribeca Film Festival has to offer are in the documentary category. Intent to Destroy, the latest from prolific documentarian Joe Berlinger, is no exception. Like his other work—most notably the Paradise Lost trilogy—this is a film that does not shy away from controversy; instead, it encourages the viewer to draw their own conclusions based on the powerful examination of all sides of an issue.

Using the framework of a behind-the-scenes look at the making of Terry George's The Promise, Berlinger dives into the history of the Armenian genocide—what happened, how it was covered up, and why the world refuses to acknowledge it.

"It's fallen on our shoulders to tell the difficult stories that networks are afraid of."

What Berlinger has produced will give you chills. Intent to Destroy is unlike any other historical account. With deft craftsmanship and a sensitivity to nuance, Berlinger breaks down the 1915 slaughter of 1.5 million Armenians by the Turkish state and the ensuing cover-up, a story that has been systematically silenced by America and Hollywood ever since. The documentary is an engaging portrait of a nation of people brought to their knees—a nation of people that is still rebuilding, 100 years in the wake of the devastation. It's a grim portrait of our world, which chose diplomacy and censorship in place of humanitarianism.

Berlinger ingeniously weaves vérité behind-the-scenes footage with interviews and archival material. The result is a framework that ties the past to the future, reminding us that our history is alive in every decision we make.

Intent to Destroy premiered to a sold-out house last week during the Tribeca Film Festival. Berlinger introduced the event. In this time, he said, "accountability has never been more important. If we're going to be human beings and interact with each other, we have to understand and accept history, and that's what this film is all about."

No Film School caught up with Berlinger to discuss what it's like to work with such dark material, how to balance your priorities as a storyteller and a journalist, and his vision for the future of independent cinema.

"You want to show both sides and allow people to come to their own point of view. It's a much more emotionally engaging experience for an audience."

No Film School: You have a history with very dark subjects, this is a particularly heavy subject. As a filmmaker, it takes so long to execute these movies. How do you sit with these subjects for so long?

Berlinger: It's true—these subjects are very emotionally draining, but I've been lucky enough in my career to see my films have a real social impact. Obviously, the most concrete example would be the Paradise Lost trilogy leading to the release of the West Memphis Three. I firmly believe that films can make a difference. Films can move and motivate people, so it's knowing that you're bringing something to light, particularly with this story.

I find it particularly morally repugnant to put geopolitics over such a basic fundamental moral issue as giving the victims of a genocide closure. As you saw in the film, America was the Armenian's greatest friend when this tragedy was unfolding—150 headlines in The New York Times, reports from the fields from Christian missionaries. The Near East Relief Effort was created and was the largest relief effort ever founded by anyone at that time, donating sums of over a million dollars to Armenian charities. So in other words, this was a bright moment in American good will and global citizenship, and that story has largely been swept under the rug because no one likes to talk about the genocide.

So how do you live with the dark stuff? You feel like you're shining a light on injustice. Even though sometimes it gets dark and depressing and frustrating, I feel like I'm combining my craft with helping people. That's how I sustain myself.

NFS: Do you see yourself as an activist?

Berlinger: Oh, totally. Generally speaking, there are three different reasons people come to documentary: advocacy, storytelling, and journalism. We all come into filmmaking for different reasons. When I made Brother's Keeper, I didn't consider myself an activist or a journalist; I considered myself a storyteller that was pushing the envelope of cinema. Once we saw the West Memphis Three sent to prison for something they didn't do, that's when I think the activist bug awakened in me. So there are three competing impulses, and sometimes those impulses are mutually exclusive.

For example, a lot of activist filmmakers feel like they have to have a very strong message, and anything that might subvert from that or show both sides and confuse the viewer is not good advocacy. I have the opposite view. Just like in Intent to Destroy, I allowed the denial people to have a voice and express their point of view. It's clear I don't believe in the denial argument, but I think you have to treat the other side with humanity and compassion so that you can understand the complexity of the issue. In Paradise Lost, 20% of the people who walked out of that film thought Damien and the West Memphis Three might've been guilty because we included such a full portrait and didn't tell you what to think. But 80% saw it the way I saw it: a miscarriage of justice. And that 80% carried a passion that led to a worldwide movement of tens of thousands of people to free the West Memphis Three.

"Sometimes what's good for journalism is bad for storytelling."

The reason you want to show both sides and allow people to come to their own point of view is that it's a much more emotionally engaging experience for an audience. If you're sitting in a theater being passively lectured to on a one-sided argument, that might be convincing in the moment while you're watching the film, but if you allow the viewer to come to their own conclusions, I think that's a more persuasive viewing experience. You become more impassioned.

Berlinger: And sometimes what's good for journalism is bad for storytelling. As a storyteller, you may want to selectively withhold information until the right dramatic moment. But is that antithetical to being journalistic? I don't have an easy answer. There are these competing impulses when you're a documentarian.

NFS: That's an interesting point about storytelling vs. journalism. When you're dealing with a subject that an audience doesn't necessarily want to hear about or might not be receptive to, what do you have to be cognizant of to keep people engaged?

Berlinger: Intent to Destroy is a good example of that, I hope. At the end of the day, even with darkest subjects, you still have to be an engaging storyteller. You still have to find a way into your subject matter, be it through a fascinating a character, a fascinating place, or some individual example that expresses a universal theme.

With Intent to Destroy, I was originally approached about doing a straightforward documentary about the genocide with just talking heads and archival footage, which is not really that interesting to me and not really that interesting to audiences. It wasn't until I ferreted out that the people who wanted me to make this straightforward documentary about the genocide actually had secret plans in the works to do this big-budget feature film called The Promise, that I knew—given the history in Hollywood of shutting down projects about the genocide because of state department pressure brought on by the Turkish government—I knew that was a historic moment.

"Everyone loves going behind the scenes of a movie—not that it was used gratuitously, but I felt that it was a good storytelling device."

I thought, "How do you make a 100-year-old event relevant and interesting to a 2017 audience?" And that was by embedding the feature film. Everyone loves going behind the scenes of a movie, movie stars, whatever—not that it was used gratuitously, but I felt that it was a good storytelling device. The film is divided into three chapters: death, denial, and depiction. Obviously, you want to give the basic history of the genocide. That first chapter, Death.... When I was first approached about making the film, that was all they wanted. It was by embedding the making of the movie that I felt I could take it to another level, which was then to then talk about the mechanism and aftermath of denial.

How do you present atrocity onscreen in a big-budget movie versus in a documentary? The way you make this interesting and acceptable is just sticking to the old-fashioned rules of cinema: you have to find interesting characters and a singular situation that is a window into a universal theme.

NFS: You spoke at the premiere about the media's responsibility to tell these stories. It's clear that you carry this mission out. With the political climate as it is right now, do you see a trend of other filmmakers in that direction?

Berlinger: I think documentary-making has never been more important. A handful of corporations own the media, and certain stories just aren't told. And as much as we'd like to pretend there's an independent press, it is now very ratings-driven and entertainment-driven. There used to be a time when the news stations and networks didn't care about commerce, but that trend ended decades ago. The news divisions of all the networks are beholden to the bottom line.

When I was doing my movie Crude, about pollution in the Amazon, I tried to pre-sell it, and I was literally told by a couple of networks who will remain nameless that "we can't sell that idea to advertisers" because they wanted to protect the big oil companies. Once it's made, of course, that's a different story: you go to Sundance, everyone loves it, and then, of course, you can sell it. But not every film goes to Sundance, is beloved, and makes deals.

"Stick to the old-fashioned rules of cinema: find interesting characters and a singular situation that is a window into a universal theme."

So there are a couple of trends that are quite distressing. The other trend is that in Hollywood, they do a handful of huge budgeted comic-book sequel movies that they hope will export around the world; that's the business model. But what has suffered is the really cool, low-to- medium-budget adult independent features, like The Crying Game or the original Miramax '90s movies that rose to meteoric heights. $10M for an indie film in the '90s was considered a big budget. So those kinds of films have fallen by the wayside significantly.

In the last 10 years, what's stepped into the void to be the new indie feature is the feature-length documentary. There's a huge increase of popularity in documentary at a time when social issue reporting is largely done by documentarians because of the other aforementioned trends. It's fallen on our shoulders to tell the difficult stories that networks are afraid of. The independent documentarian's role has never been more important.

For more, see our complete coverage of the 2017 Tribeca Film Festival.