Discover How 'Crown Heights' Director Matt Ruskin Went From IFP to Winning Sundance

The journey to winning the Audience Award at Sundance 2017 started at IFP Film Week.

Like the best kind of college advisor, the Independent Filmmaker Project nurtures storytellers. For projects ranging from development to distribution, the IFP offers time and resources, connects creative talent with financiers, executives, mentors and collaborators, and curates events to help open doors—all in hopes of seeing you accomplish great work. One of their annual programming highlights is IFP Film Week. Designed to help launch ideas and boost careers, its events are abuzz with filmmakers, artists and storytellers.

This year, one of the filmmakers was writer/director Matt Ruskin, appearing on a panel moderated by Variety film critic-turned-Amazon exec Scott Foundas. Ruskin was there as an IFP alum to share his serendipitous tale of how his second narrative feature—working title, Darker Than Blue—went through IFP Film Week 2015, then went on to win the Sundance Audience Award earlier this year under the new title Crown Heights.

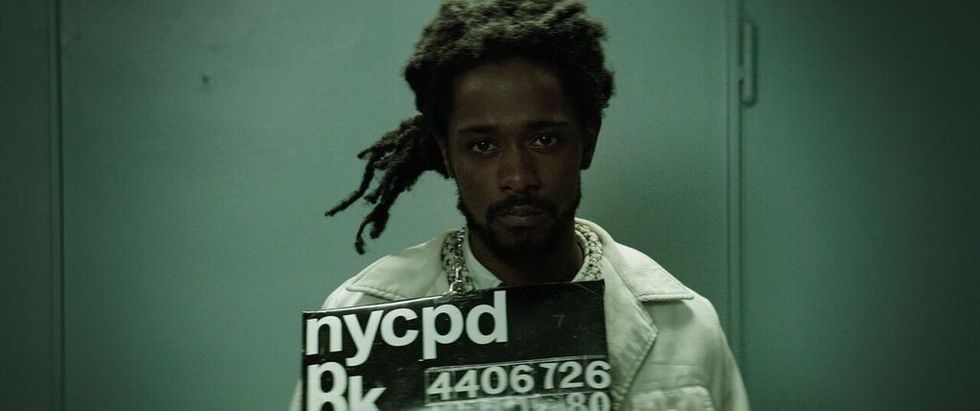

Ruskin’s film is the powerful—and painfully timely—biographical drama that retells the true story of Colin Warner: a man who spent 21 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. Purchased at Sundance by Amazon, Crown Heights had its theatrical premiere this past August. You’ll soon be able to watch it on VOD and Amazon Prime.

Ruskin credits the IFP for much of his successful journey. “It’s an incredible support system for independent filmmakers in New York,” he enthused. “I’ve been involved with the IFP for a while now, between Crown Heights and a Filmmakers Lab where I was working on Booster, the movie I made years before this one. A huge part of my network is all through people I’ve met here, filmmakers in the trenches trying to do similar things. And with the script for Crown Heights, I did rounds of meetings with producers, all set up by IFP. One of those meetings led to a grant from the Tribeca Institute, which was incredibly helpful.”

Here are the top eight takeaways that Ruskin shared with the crowd.

1. Seize luck when you see it

Like so many film journeys, Ruskin’s route was circuitous. He dropped out of college to apprentice for a chef in Boston where he’d grown up, then decided he didn’t want to cook for a living. He mentioned his interest in film to the guy managing the restaurant—who happened to be a college friend of filmmaker Darren Aronofsky. Ruskin asked if he could approach the director.

“Two months later, I was prepping Requiem for a Dream,” Ruskin laughed in disbelief. “That was my introduction to filmmaking. It was a great experience, and I was totally smitten: I now had the film bug.” Luckily for him, he didn’t know how hard it was to get to the stage where you’re actually able to prep a film. “I didn’t realize how good Aronofsky had it till later,” he added, rolling his eyes.

For a while, Ruskin made docs, developing his ability to tell a human story grounded in truth. Then, listening to NPR one day in 2010, he heard Colin Warner’s story on This American Life. He was profoundly moved.

“I tracked down the reporter,” he recalled, “only to find out that the story was a rebroadcast. It had aired five years earlier. Two studios had already optioned the rights, separately, but never scripted it.” Classic Hollywood. Hoping that he could do better, Ruskin decided to tackle the project himself. He approached both Colin Warner and Carl ‘KC’ King, Colin’s friend who had spent years trying to prove Colin’s innocence, and they saw him as a welcome change.

2. Trust your instincts

Yes, Warner and King are black. And yes, Ruskin is white. During the course of making Crown Heights, Ruskin has been subject to some “Why you’s”; but he is far from the “white savior” model, and there is nothing manipulative or maudlin about his telling of Warner’s story.

“If a story moves you on a deep level, don’t question your right to tell it. That’s the whole point of being a storyteller.”

“I don’t want a society where you have to be a certain race to tell a certain type of story,” he declared. He cited Steve McQueen’s film Hunger, about the hunger-strike led by Irish prisoner Bobby Sands as a parallel example. “McQueen had no ties to Bobby Sands' story besides being moved by it, but he decided to make that film anyway. So if he can do that, then maybe I can make the Colin Warner film.” He paused, leveling his gaze at the audience. “If a story moves you on a deep level, don’t question your right to tell it. That’s the whole point of being a storyteller.”

Ruskin’s passion for the project is what made it happen. “I grew up in liberal New England, so social justice issues were always on the horizon,” Ruskin explained. “But even so, I certainly didn’t set out to make a film about the criminal justice system. I was just so blown away by Colin and Carl, and how they’d handled themselves throughout all of this.”

Getting their approval was easy. Finding someone to fund it was a lot harder.

3. Find investors who share your passion

So how did Ruskin finance his Sundance-winning film? Coming from a doc background, with only one small narrative feature under his belt, didn’t help.

“I went to like 100 potential investors,” Ruskin remembered. “I started with a list of people who might be interested in this kind of subject matter: all those who have taken on mass incarceration, social justice issues. But even with that target audience, it was a lot of getting told ‘No.’”

He winced at the memory. “It was the chicken or the egg conundrum: ‘I’ll finance your movie if you have a cast,’ they’d tell me. ‘I’ll consider acting in your movie if you have financing.’” He gave an exasperated laugh, shook his head. “You have to inch everything forward simultaneously. And use whatever tools you have in your arsenal.”

“You just have to remember: you may get a lot of no’s, but it only takes one yes to get things rolling.”

In Ruskin’s case, he used his talent for documentary filmmaking to sell his idea. He shot doc-style interviews with the real-life Warner and King, then cut together a proof-of-concept piece to show to potential investors.

After many failed meetings, someone finally said yes: a new company of private investors agreed to add his film to their slate. “Once they were on board, it was easier to get others interested because the project looked much more likely to happen,” Ruskin grinned. “You just have to remember: you may get a lot of no’s, but it only takes one yes to get things rolling.”

4. Cast with care

While he was still out there pitching, Ruskin got the attention of casting director Avy Kaufman (The Sixth Sense, The Bourne Ultimatum, Life of Pi, Brokeback Mountain), “mainly because she, too, was moved by the story,” he explained. “Avy has a reputation for doing huge movies, but then she’ll take on a little movie she thinks is important. Luckily, this time it was mine.” He paused, savoring his good fortune. “She gets people’s attention when she calls, and she brings an incredible wealth of knowledge about New York actors.”

“That’s one thing I’m really proud of, the actors in Crown Heights,” he continued. “That was a major takeaway for me. I learned that working with really great actors is the most important thing. If you have a solid script and cast the movie well, you’ve done most of your job.”

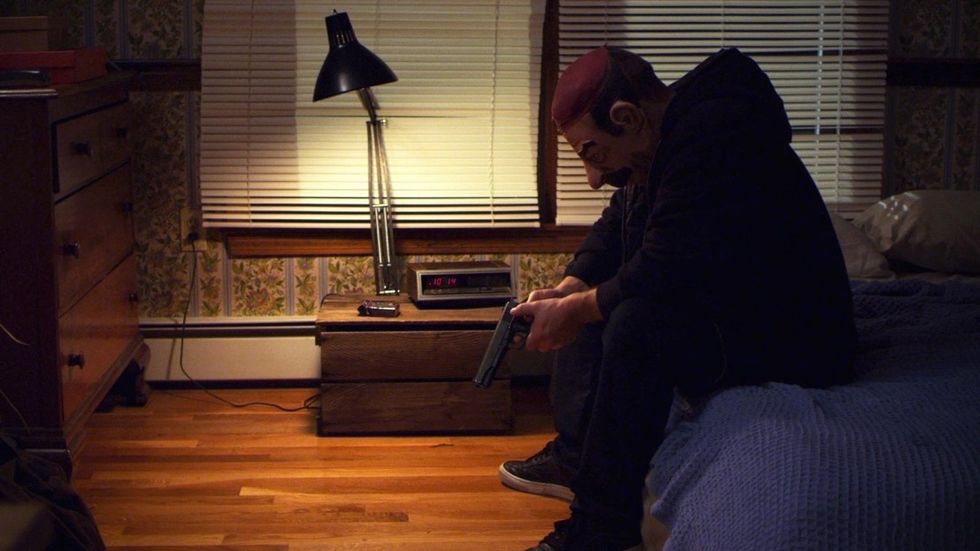

Ruskin’s lead is the masterful Lakeith Stanfield, an exploding talent who’s mostly shown his multifarious chops in Atlanta, Straight Outta Compton, and Get Out. “I’d seen Keith in Short Term 12. He had this incredibly genuine ability to be vulnerable on camera, which I thought would serve this character well. I sent him the script, and he was really moved by Colin’s story. He became a passionate collaborator.” Ruskin smiled, still grateful.

“That’s the silver lining of making a movie on a relatively low budget. You don’t get bogged down in conversations about foreign pre-sales, box office sales, attaching the right names to the film.”

Then came Nnamdi Asomugha, who plays Warner’s friend Carl King. “He just started calling me, really persistently, over the space of a couple months,” Ruskin remembered. “I wrote him off at first, because I only knew of him as a football player. And how ironic,” he laughed. “Usually, that’s me: I’m the guy calling someone 100 times, trying to get them to read a script. So I thought I should give this guy an hour of my time. And he brought in a scene partner, we workshopped a couple of scenes. By the end of the audition, I was convinced there was no one else for the role.”

There’s a lesson for aspiring actors: be persistent, come prepared and bring your A-game. And treasure those indie projects. An independent director can decide to cast you without executives weighing in on his choices. “That’s the silver lining of making a movie on a relatively low budget,” Ruskin reminded us. “You don’t get bogged down in conversations about foreign pre-sales, box office sales, attaching the right names to the film.”

5. Let the story come first

Ruskin was also tenderly attentive to his subject matter. “It was important for me to make a film that wasn’t hitting people over the head with the issue,” he declared. “As a viewer, I personally shut down when I feel a film is one part-public service announcement. My hope was that when people see Crown Heights, they would think about the overarching issues, but that the story would come first.”

The initial draw for Ruskin was how impressed he was by Warner and King, by the decisions they made. “That’s what really hooked me,” he said. “So my goal was to approach the film on a humanistic level.”

Ruskin decided to write the script in a linear structure, to preserve the sense of shock and confusion that the characters experience early on, and to help his audience feel it along with them. “I tried to hit the critical moments along the way,” he explained. “Both in their lives, when they were challenging this unjust conviction, and in the political rhetoric, when the policies of the time were cracking down hard on crime.” As a result, the weight of Warner’s crime—a crime that he didn’t commit—infiltrates the film like a cancer, afflicting the audience as well.

“I tried to incorporate their own words into the film as much as possible.”

A lot of the dialogue also comes from real life: court transcripts from the trial; the parole hearing; Ruskin’s hours of recorded interviews with Warner and King. “The interviews were essential,” Ruskin insisted. “We worked some amazing details into the script because of them. I tried to incorporate their own words into the film as much as possible.”

The actors drew from real life as well. Ruskin encouraged them to spend time with the real guys, and really get to know them. “Keith spent a week with Colin in Georgia, trying to get to know him and his family,” he said proudly. “Nnamdi did same thing, went to Georgia to meet Colin and then spent a week in New York getting to know Carl. Since the real guys were willing, it was a great opportunity for my actors to connect with the personalities they’re portraying. We were telling their life stories, after all. But once we got to production, there was a degree of separation: the real guys stayed back, and let the actors do their thing.”

6. Make a lot out of a little

Subject matter aside, Crown Heights was a logistical challenge: a low-budget period film, with characters who had to age convincingly over the course of multiple decades. Ruskin shook his head. “It was tough to make this kind of film with the budget we had,” he admitted. “I’m just lucky that everyone felt so committed to telling this story. If this was my vanity horror film, nobody would speak to me again.”

Fortunately, logistical challenges often lead to innovative stylistic inventions. Shot in anamorphic with surprisingly poetic touches, Crown Heights captures its years-spanning mix of confinement and freedom by intercutting shots in confined spaces with flashbacks to Colin’s youth in Trinidad. The result? Claustrophobic, dynamic, and emotionally compelling. And the budget constraints don’t show.

Bruce Davidson’s photography book Subway was a crucial reference. “It was a time capsule to 1980s Brooklyn,” Ruskin elaborated. “The name of the game was trying to do so much with so little. We knew we had to conserve time, so we found older buildings where we could shoot multiple locations at once, and then we reused those locations simply by changing the furniture. We also used a lot of dead end streets, with no long views. We strategized how to make a street look full with only five period cars. We drew a lot of diagrams.”

“I’m just lucky that everyone felt so committed to telling this story. If this was my vanity horror film, nobody would speak to me again.”

They shot in 40-something locations in 27 days: “a incredibly demanding, crazy schedule,” Ruskin admitted. “I don’t think the crew would have hung in there with us if we hadn’t been so prepared. Most of the logistical issues were hammered out in prep.” One of those issues was his characters’ aging process. Ruskin worried that changes like gray hair and makeup might be over-the-top, and distract from the story—so he decided against it. “We just adjusted facial hair, body weight and wardrobe,” he shrugged. “It’s surprising how much you can change with that. And it helped us save time.”

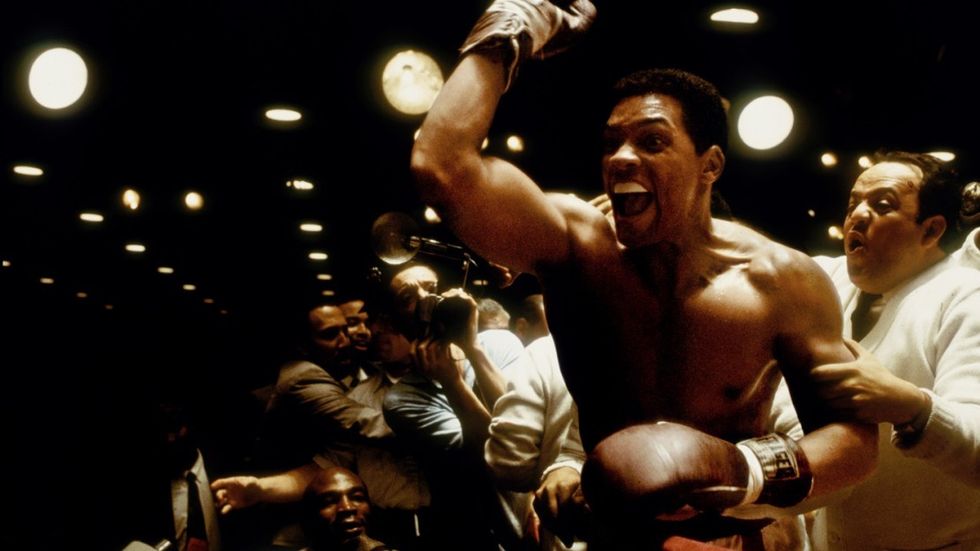

They made other stylistic decisions before shooting began. Ruskin’s cinematographer, Ben Kutchins, insisted on using older, Cooke anamorphic lenses, to give everything a texture, a more dated feel. “We didn’t want that crisp digital look,” Ruskin confirmed. “Instead, we screened older films to find looks that we liked.” One of their visual ‘guiding lights’ was a Ali by Michael Mann. “There was a doc element to that film which appealed to me,” Ruskin explained, “a controlled handheld feeling that makes you feel like you’re right there in the room. It’s a great mix of intimately visceral cinéma vérité paired with these really sweeping cinematic moments.”

And as for the flashbacks, they were inspired by Diving Bell and the Butterfly. “That film explores confinement in a wonderfully different context, a juxtaposition of memory and imagination. So we thought that would be a good way to explore Colin’s inner-psyche while he was in prison.”

7. Savor the moment

The hard work paid off. Before the Sundance awards were even announced, Ruskin had already sold Crown Heights to Amazon. “It wasn’t like a mad bidding war,” he laughed. “We loved what Amazon was doing—what they’d done with Manchester by the Sea—and we wanted our film to end up there.” Luckily for Ruskin, his lead actors were represented by CAA, who wound up negotiating the deal with Amazon. “They felt interest in the project, and agreed to sign on as sales agents.” He grinned. “There’s something to be said for having a reputable sales agent, it really lent me some legitimacy.”

Then the film won the Audience Award at Sundance. “The response was incredible,” Ruskin recalled with a sense of wonder. “It was great to see how moved Colin and Carl were, to see that so many people were interested in their story, that so many were touched by what they’d been through. It was a really gratifying moment.”

Ruskin smiled, bringing his story full circle. “I wouldn’t be here now if it weren’t for IFP. I wouldn’t have gotten into Sundance, I wouldn’t have won the Audience Award. I didn’t really exist until after Sundance. Then all of a sudden, my film was on the map and so was I. And now: to have a work sample out there, to have an opportunity to meet with people about bigger films, well… That’s life-changing.”

8. Treasure your freedom

At the close of their panel, Scott Foundas asked Ruskin how he feels about his film after the fact, comparing him to post-Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard who was notoriously arrested in the Louvre for trying to retouch his own paintings. “Yeah, I’m like one screening away from that,” Ruskin deadpanned. “I would change SO much about Crown Heights. I’ve lived with this film for so long that it’s hard to see anything but the flaws.”

The crowd laughed, but he wasn’t kidding. “The learning curve for this film was really, really steep. The film I did before this was budgeted at only $50,000, and I was living in my parents' home in Boston. You can shoot movies by yourself on the weekends with an iPhone, but it’s very different than working with a real crew.” He paused, almost wistful. “Back when I did the IFP lab, I was only thinking creatively. I was focused on the story I wanted to tell. But now, I find myself trying to figure out what will sell more tickets at a movie theater. And I’m not sure I like that.”

He looked out at the people sitting where he used to sit. “You guys may not appreciate it right now, but you just might be in the most unfettered creative moment of your entire film career. You’re not dealing with financiers, focus groups. You should embrace that opportunity and tell whatever kind of story you’re burning to tell.”

Featured image: Lakeith Stanfield in 'Crown Heights'. Credit: Amazon Studios.