4 Takeaways from Bradford Young on the Daily Grind of Being a Cinematographer

Bradford Young has only been working professionally for a decade and yet he's already a legend in the industry.

Bradford Young, the maverick cinematographer, has likely shot one of your new favorite films. His work can be found in projects with as diverse a range of subjects as they are in budgets. He's been linked to directors Ava DuVernay and Dee Rees from the beginning of their careers, shooting their early features, Middle of Nowhere and Pariah, respectively.

Young has shot urgent documentaries like Free Angela and All Political Prisoners, contemplative fiction like Ain't Them Bodies Saints, A Most Violent Year, Selma and Arrival, and most recently lensed the mega-budgeted Solo: A Star Wars Story.

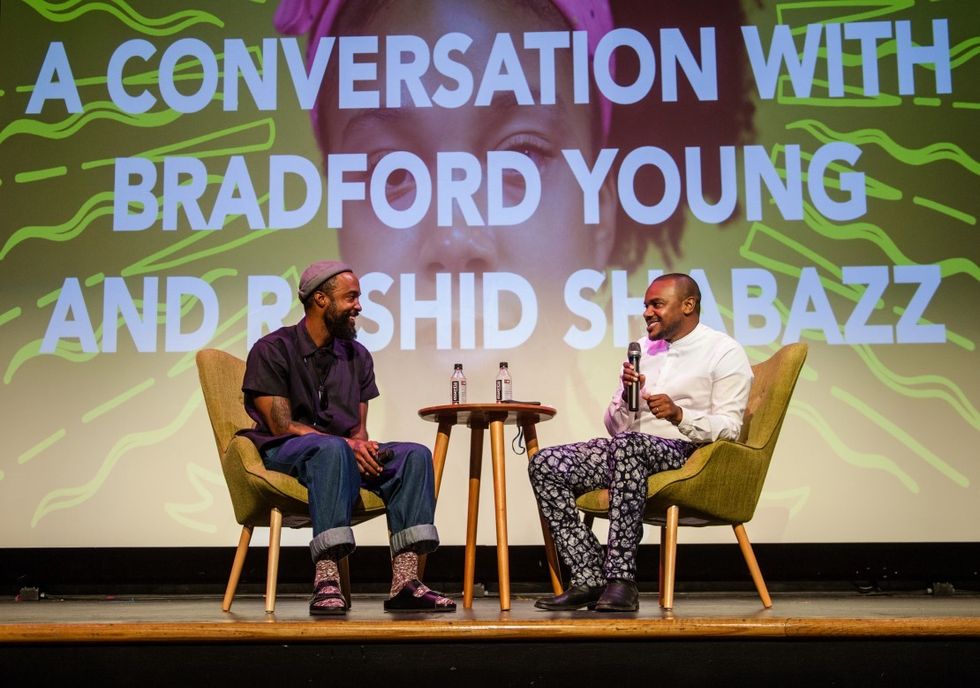

At this year's Blackstar Festival, Young sat down with the writer and activist Rashid Shabazz, a lifelong friend, for a discussion of blackness, cinema, and the power of an image that doesn't ask for permission. Shabazz opened with a succinct appraisal of Young's work. "You are, in my opinion, one of the greatest cinematographers, not just of this generation, but of all time. I didn't signify with the word 'black', I'm saying cinematographer. In every film I watch by you, the thing I love most is the texture of the depth that you bring to us as a people. But more importantly, every frame I watch I could take and put it on the wall."

1. On sensitivity as a cinematographer

Bradford Young: When you have friends who you've known longer than 20 years and are arguably better human beings than yourself in many ways, I find it hard to show up to work and not work hard. My grandfather was no-nonsense; it was clear from an early age that he expected certain things from us. That burden and that gift is with me now. When I show up for work as a cinematographer, I work hard. It's a healthy sense of fear and I try to pull from that.

That sense of community. It's not even about the lighting or the texture, I mean it is, but there's a part of me that's thinking, okay, here's the square, not to be technical, but here's the square. What's the scene, what's the story in this shot? I do this in order to feel like I know what I'm doing, and not walk out of the room crying and saying "what am I doing?"

After all that hard work, you do your due diligence and tell the story that's on the page. In my form as a cinematographer, I still feel like I'm just a service provider. I'm a blue collar worker. I'm there in service of the story and the director. Anything you see on screen, the director has complete ownership of. I just have to make sure I do the hard work to make sure everything in the director's mind's eye winds up on screen.

All that texture you see has a lineage, because I'm totally biased. I think good lighting is one thing and not another. It's very black and white that way. I pull from fear, anxiety, my pedagogy that got me here, the books I read as a kid, the picture books I looked at.

2. On being held accountable by your community and family

Young: It's all wack when I see my (wife and two children). That puts it all into perspective anyway. That makes everything in my practice less precious. That's become more and more apparent over the last five years. I look at my oldest child and it doesn't feel the same anymore. The first point of accountability is to not have a conversation about it at all. The work is not that important (when you've got a family to take care of).

"As an artist or practitioner, of course, your practice is important, but the things we aspire for, the things we want from people who don't like us, have no love for us…it doesn't mean anything when you come home to family, your partner who's been through all your bullshit with you, your kids… [it means more than] trying to win an Academy Award or whatever the nonsense is when you're in the process of making films which haven't been able to shake off the shackles. That's the first step.

3. On having a back-up plan

I said this to Ava Duvernay the other day: 'The minute we start making films like Oscar Micheaux, we're done. The minute we incorporate white supremacist imagery in our films, we out. Because we ain't gonna win awards anyway. The minute we start doing that, we have to have a landing pad to get out of the conversation.'

Don't expect cinema to address our needs. Our music is crazy. I'm listening to this cat Grips that Shawn Peters hipped me to. I'm just like, 'film is wack. Cinema is wack because it can't equate to the way a bell or a drum pattern or a bit of black silence touches us.'

The films that have achieved that…Ashes and Embers, To Sleep with Anger, Killer of Sheep, Passing Through, Daughters of the Dust, you know what I'm saying? In The Morning, Random Acts…all those things, they check in, and that's why we feelin' em.

4. On the classification of a Black Cinema

Young: It starts with a commune, a collective idea. This question of what is Black Cinema? Who are you to define what black is? But again, if we have community and we have a conversation…the conversation around what Black Cinema is, until we become fully developed human beings in this hemisphere and realize ourselves the conversation around black cinema is gonna be part fascist, you know?

This is the way, this is the only way! It's going to be very egalitarian because everybody's going to have opinions. I think we should have both because both are healthy, especially with underdeveloped people. So for me? As an undeveloped human being, a terribly undeveloped human being, my challenge is, for me: cause it's a black director, cause it's black actors, cause it's got black money behind it. The grammar behind it, that's what makes it black. People have a hard time saying what is Black Cinema. I'm saying…better get ready for it.